‘The Adventures of Huck(leberry) Finn’ 1939 vs 1993

CommentaryMark Twain’s 1884 novel “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is often called the great American novel. Although technically a sequel to his 1876 novel “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “Huckleberry Finn” ended up overshadowing its precursor. The dynamic story about a free-spirited boy who escapes his abusive father by floating down the Mississippi River with a runaway slave lends itself well to dramatic adaptation, so it has been made into countless film, television, and stage productions. One of the story’s earliest films was “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” a 1939 MGM production starring Mickey Rooney. It was preceded by two silent films and one 1931 talkie adaption, but this was the first time Huck’s story was adapted into a standalone film rather than a sequel to some version of “Tom Sawyer.” This movie’s compact, simplified plot set the tone for future standalone adaptions, including Disney’s 1993 “The Adventures of Huck Finn,” starring Elijah Wood. The 1939 and 1993 films stand out from other versions of this story for their originality, clarity, and strong eponymous leads. While similar in many ways, a few key disparities make these films vastly different overall. Let’s consider both movies’ faithfulness to the book, story changes, and wholesomeness to determine which is the better film. Cover of the book “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain, 1884. (Public Domain) A Good Adaption or a Good Film Filmmakers in the 1930s were more interested in making entertaining, effective films than faithfully adapting the source material, so it’s not surprising that the 1993 version contains more elements from the original book. Early in the novel, Huckleberry’s drunken father wants the treasure Huck and Tom found during “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” so he takes the boy away from the Widow Douglas and Miss Watson, bringing him to his cabin. With Tom Sawyer not included, the 1939 screenplay instead had Pap Finn demand $800 from the Widow and Miss Watson to leave Huck with them. The 1993 film combined these ideas, with Pap wanting $600 which Huck inherited from his mother. Instead of leaving the women willingly in order to protect them, like the 1939 Huck, the 1993 Huck is dragged out of the house by his father. Both films reduced the length of Huck’s stay in Pap’s shack from months to roughly a week in the 1939 movie and one night in the 1993 version. Huckleberry Finn and Jim, on their raft, by E.W. Kemble from the 1884 edition of the book “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” (Public Domain) Another important character is Jim, a slave who belonged to Miss Watson in the book and the 1993 movie but to Mrs. Douglas in the 1939 adaptation. Like the novel, the later film has Miss Watson reluctantly decide to sell Jim because a slave trader offers her $800, whereas the Widow only plans to sell him in the earlier movie because she needs the money to appease Huck’s father. The 1939 Jim wants to escape to the free state where his wife and son live, but the 1993 Jim’s wife and children also belong to Miss Watson. He plans to buy them out of slavery, like in the book. In both films and the book, Jim discovers Pap’s corpse aboard a wreck on the river, but he doesn’t tell Huck. Near the end of both films, Huck is deeply hurt to learn that Jim kept the secret to ensure he would help him escape, although the incident is more important in the 1939 version. When Huck learns of his father’s death at the end of the book, he doesn’t really care. Each movie only includes some of the book’s adventures. For instance, in the 1993 film, Huck and Jim spend time at the Grangerford plantation, where Huck enjoys luxury while Jim is enslaved again; there, they get caught in the crossfire of a deadly feud. This part of the book was not used in the 1939 film. Later, Huck and Jim meet a pair of conmen, the King and the Duke, who hitch a ride on their raft. While they are independent swindlers in the same town in the book, they are already a criminal team in both films. They enter the 1939 movie by getting tossed off a riverboat, whereas they enter the 1993 film and the book while running from lawmen. However, only the 1939 version kept the book’s device of their inventing royal titles to impress Huck and Jim; in the 1993 adaptation, they call themselves noblemen without explanation. In the 1939 film, the King and the Duke are planning all along to visit the Wilkes estate and impersonate the British brothers of the recently deceased Peter Wilkes. Along the way, they dishonestly perform “Romeo and Juliet,” which is one of their many swindles in the book. However, in the 1993 version, they learn about the Wilkes opportunity after meeting Huck and Jim, as in the book, yet they don’t engage in any other skullduggery during the trip. Both films omit the book’s unpopular “fourth act,” instead ending after the Wilkes scenario. While the 1993 copied the book’s conclusion of Miss Watson’s dying and setting Jim free in her will,

Commentary

Mark Twain’s 1884 novel “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” is often called the great American novel. Although technically a sequel to his 1876 novel “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “Huckleberry Finn” ended up overshadowing its precursor. The dynamic story about a free-spirited boy who escapes his abusive father by floating down the Mississippi River with a runaway slave lends itself well to dramatic adaptation, so it has been made into countless film, television, and stage productions.

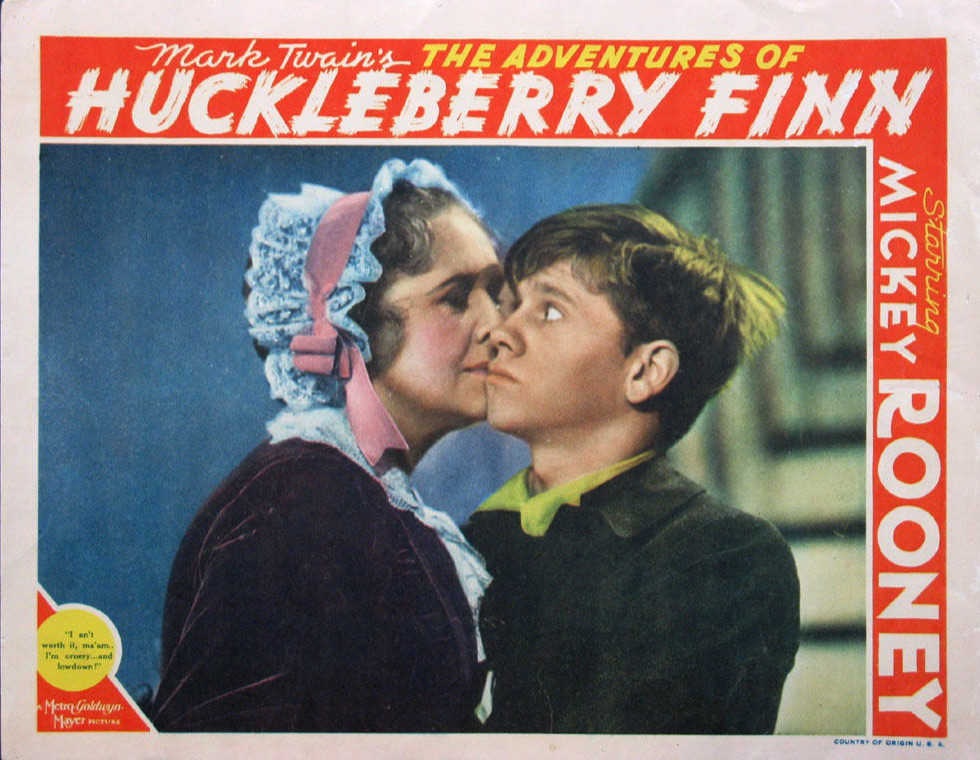

One of the story’s earliest films was “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” a 1939 MGM production starring Mickey Rooney. It was preceded by two silent films and one 1931 talkie adaption, but this was the first time Huck’s story was adapted into a standalone film rather than a sequel to some version of “Tom Sawyer.” This movie’s compact, simplified plot set the tone for future standalone adaptions, including Disney’s 1993 “The Adventures of Huck Finn,” starring Elijah Wood.

The 1939 and 1993 films stand out from other versions of this story for their originality, clarity, and strong eponymous leads. While similar in many ways, a few key disparities make these films vastly different overall. Let’s consider both movies’ faithfulness to the book, story changes, and wholesomeness to determine which is the better film.

A Good Adaption or a Good Film

Filmmakers in the 1930s were more interested in making entertaining, effective films than faithfully adapting the source material, so it’s not surprising that the 1993 version contains more elements from the original book. Early in the novel, Huckleberry’s drunken father wants the treasure Huck and Tom found during “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” so he takes the boy away from the Widow Douglas and Miss Watson, bringing him to his cabin. With Tom Sawyer not included, the 1939 screenplay instead had Pap Finn demand $800 from the Widow and Miss Watson to leave Huck with them. The 1993 film combined these ideas, with Pap wanting $600 which Huck inherited from his mother. Instead of leaving the women willingly in order to protect them, like the 1939 Huck, the 1993 Huck is dragged out of the house by his father. Both films reduced the length of Huck’s stay in Pap’s shack from months to roughly a week in the 1939 movie and one night in the 1993 version.

Another important character is Jim, a slave who belonged to Miss Watson in the book and the 1993 movie but to Mrs. Douglas in the 1939 adaptation. Like the novel, the later film has Miss Watson reluctantly decide to sell Jim because a slave trader offers her $800, whereas the Widow only plans to sell him in the earlier movie because she needs the money to appease Huck’s father. The 1939 Jim wants to escape to the free state where his wife and son live, but the 1993 Jim’s wife and children also belong to Miss Watson. He plans to buy them out of slavery, like in the book. In both films and the book, Jim discovers Pap’s corpse aboard a wreck on the river, but he doesn’t tell Huck. Near the end of both films, Huck is deeply hurt to learn that Jim kept the secret to ensure he would help him escape, although the incident is more important in the 1939 version. When Huck learns of his father’s death at the end of the book, he doesn’t really care.

Each movie only includes some of the book’s adventures. For instance, in the 1993 film, Huck and Jim spend time at the Grangerford plantation, where Huck enjoys luxury while Jim is enslaved again; there, they get caught in the crossfire of a deadly feud. This part of the book was not used in the 1939 film. Later, Huck and Jim meet a pair of conmen, the King and the Duke, who hitch a ride on their raft. While they are independent swindlers in the same town in the book, they are already a criminal team in both films. They enter the 1939 movie by getting tossed off a riverboat, whereas they enter the 1993 film and the book while running from lawmen. However, only the 1939 version kept the book’s device of their inventing royal titles to impress Huck and Jim; in the 1993 adaptation, they call themselves noblemen without explanation. In the 1939 film, the King and the Duke are planning all along to visit the Wilkes estate and impersonate the British brothers of the recently deceased Peter Wilkes. Along the way, they dishonestly perform “Romeo and Juliet,” which is one of their many swindles in the book. However, in the 1993 version, they learn about the Wilkes opportunity after meeting Huck and Jim, as in the book, yet they don’t engage in any other skullduggery during the trip. Both films omit the book’s unpopular “fourth act,” instead ending after the Wilkes scenario. While the 1993 copied the book’s conclusion of Miss Watson’s dying and setting Jim free in her will, the 1939 had a reformed Huck persuade Mrs. Douglas to free Jim.

Disney vs. MGM

If I had to guess which of these is a Disney film, historical clues aside, I would choose the 1939 version. It’s playful, wholesome, fun, and very family friendly. In contrast, the 1993 story is darker and more dramatic, including elements which the earlier film omitted. For instance, the 1939 film skipped the frightening scene from the book when Pap tries to kill Huck in a drunken fit, which is included in later versions. The 1939 Huck even uses ketchup instead of pig’s blood to convince his father he’s been murdered. Both films added an anti-slavery message spoken by Jim and Huck, although it’s much more pointed in the later one. The 1930s picture also features an 1840s message of equality, spoken by an abolitionist who quotes future president Abraham Lincoln.

It’s not surprising that the MGM film contains the wholesome charm typically associated with Disney, considering its era. During Hollywood’s Golden Age, Walt Disney Studios wasn’t the only company that strived to make famous stories acceptable for families. From 1934 to 1954, the Production Code Administration (PCA), a Hollywood self-regulation council that enforced the Motion Picture Production Code, ensured that all movies were “reasonably acceptable for reasonable people.” When PCA boss Joseph I. Breen retired in 1954, most filmmakers abandoned the Code’s standards. Disney Studios alone maintained the Code’s standards of wholesome entertainment for all ages during the late 1950s and ‘60s. Unfortunately, after Walt Disney’s death in 1967, his studio began including off-color humor and onscreen violence, which neither Mr. Disney nor Mr. Breen would have allowed.

In terms of content, “The Adventures of Huck Finn” is a far cry from 1960s Disney live action films like “Swiss Family Robinson.” Both Huck and Pap belch loudly, a rude comedic gag which the Code forbade but modern filmmakers think is appropriate children’s humor. This movie was rated PG “for some mild violence and language.” The language includes around twenty uses of the words “damn” and “hell” as pointed profanity, mostly said by Huck himself! While the book referred to Huck and others swearing, no profane words were written. Naturally, the Code version includes no swearing. Regarding violence, the 1993 film features grotesque corpses onscreen, and Huck gets shot near the end instead of being bitten by a rattlesnake, as in the 1939. Although he recovers, this is a disturbing moment. Some call the later film’s ending “Disneyfied,” but the earlier movie’s ending is brighter and more conclusive. Nevertheless, it’s wrong to assume that happy endings were added to Breen Era movies because of the Code. It was not Joe Breen but MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer who insisted the studio’s films end happily.

Simplicity

Filmmaking styles changed a lot from the 1930s to the 1990s. In the 1930s, the studio system ruled Hollywood; it turned out movies quickly and in high volume. Films were often made according to proven formulas. By the 1990s, films had increased runtimes, budgets, production schedules, and even larger, more eclectic casts rather than standard picks from the studio’s top talent. These two versions of “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” reflect trends in their respective eras of production.

The core of each film is the actor playing Huck Finn. Mickey Rooney was eighteen years old, four years older than the character’s age in the book, while eleven-year-old Elijah Wood was younger by almost as much. Though very different, both boys give amazing performances. Mickey’s Huck is river-smart but sensitive, while Elijah’s Huck looks very dainty yet acts much tougher than his older counterpart. I think Elijah was costumed much too neatly throughout the film, whereas Mickey looks sufficiently ragged. Although he’s not above lying and stealing to survive, it’s clear that the 1939 Huck Finn is a good boy at heart, never losing his Andy Hardy innocence. Ironically, the significantly younger, almost pretty 1993 Huck is an unapologetic fibber with a well-developed streak of larceny. Although he too shows bravery and compassion toward Jim, I wonder whether he will accept Mrs. Douglas’s guidance, like in the 1939 film, or will shun love for freedom, as in the book.

I think the main element the 1993 film lacks is Southern charm. The whole movie was filmed on location in Mississippi, while the 1939 film only supplemented soundstage footage with a few location scenes shot in Alabama and Northern California. The 1993’s makers tried harder to faithfully adapt the book by including more of the book’s scenarios. However, at only 108 minutes, it didn’t have enough time to develop these scenarios. Perhaps the main reason why the later film didn’t capture the picture of the carefree boy floating down the river was that he spent most of the film running for his life!

Music also greatly influences a film’s tone. The 1939’s playful score by Franz Waxman included banjo music, simple Southern tunes, and plucking strings reminiscent of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves.” The 1993 film’s sweeping score by Bill Conti is beautiful and moving, yet it fails to evoke the book’s homespun Southern simplicity for me.

Are the 1993 film’s differences from the 1939 movie improvements, or did it re-make too much of things?

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.