Minister Briefed on Chinese Police Stations in Canada Only in Last Year, Despite Online Post About It as Early as 2020

News Analysis Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino recently told MPs that he was briefed about unofficial overseas Chinese police stations in Canada only within the past year. However, The Epoch Times reported this week that a post about one such location in Richmond, B.C., was published online by a regional Chinese police bureau as early as 2020. The revelation that the minister in charge of Canada’s intelligence and security agencies was only briefed about the issue in the past year raises a number of questions. Were the agencies unaware of this open-source information, and only learned about this Chinese Communist Party (CCP) threat at the same time as the media, after NGO Safeguard Defenders released a report on the overseas stations in September 2022? Or if the agencies were aware, did they decide not to brief the minister? This is an issue of such significance that, after coming to the public’s attention, was raised by Canada’s prime minister with China’s leader, and led to Global Affairs Canada summoning the Chinese ambassador multiple times for an explanation. Phil Gurski, a veteran of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), says there could be another possibility. “[Third] possibility: CSIS did brief senior officials, but this was not passed on to the minister for fear of upsetting Canada-PRC [People’s Republic of China] relations,” Gurski said in an email. Scott McGregor, a former Canadian Armed Forces intelligence operator who also served as an intelligence adviser to the RCMP, says he’s confident Canada’s security agencies have been aware of these overseas police operations for years. A sign for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service building is seen in Ottawa in a file photo. (Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press) But he says the issue didn’t get government attention for the same reason that many other threats from China go unaddressed: lack of political will. “What are you allowed to do about it? If you don’t have the resources, the laws will not allow you to enforce anything, so no one’s going to jail,” McGregor, who is now a private investigator and founder of Close Hold Intelligence, said in an interview. “Are there laws that could be used? Certainly. But you’d have to have the support of the government in order to pursue those things, and because the government is so heavily invested and influenced, there is no political will.” Trend McGregor says he observed this reluctance to take on issues related to China first-hand in the mid-2010s when he was working in law enforcement in B.C., where there are major CCP-linked fentanyl-trafficking and money laundering operations through casinos and real estate transactions, driving the province’s rampant opioid crisis. “We attempted to provide information that would go to the minister [of finance of B.C.] on what was happening with transnational organized crime and its connection to the Chinese, etc., and it was stonewalled,” he says. When it comes to the issue of Chinese police, McGregor says Canada’s naivete on the issue is best characterized by how the Justice Institute of British Columbia (JIBC) partnered with China’s Public Security Bureau to train Chinese police in the province beginning early last decade. The program was ended in 2019. An excerpt from IJBC’s 2018-2019 annual report shows information about Chinese police being trained by the organization. (Screen capture) “Why are you training the Chinese police? They have a 99 percent conviction rate. Their laws are not congruent to ours,” he says. “You’re accepting money from an authoritarian government to train their police in our methodologies, when you know that their espionage and collection of intelligence targets all aspects of our society in an effort to undermine it.” McGregor says this is yet another example of the senior ranks of security agencies knowing such a program was wrong, yet it was allowed to proceed because they “don’t think there’s anything they can do about it.” The Epoch Times contacted JIBC but the organization said it would need a week or two to comment. Gurski concurs there’s a general sense in the intelligence community that there exists an unwillingness within the political class to deal with the China threat. “CSIS has been warning about this for 25–30 years. We’re talking about Chinese theft of Canadian technology, we’re talking about interference in distinct communities,” he writes. “We were ignored, because they saw the Chinese economic relationship as more important.” A joint report by the RCMP and CSIS in 1997 titled Project Sidewinder, which was leaked to the media, warned about the CCP’s infiltration, influence, and espionage operations in Canada through means such as using criminal gangs and business tycoons. A 2000 publication by the Security Intelligence Review Committee, the governmental body that oversaw the operations of CSIS back then, dismissed the concern

News Analysis

Public Safety Minister Marco Mendicino recently told MPs that he was briefed about unofficial overseas Chinese police stations in Canada only within the past year.

However, The Epoch Times reported this week that a post about one such location in Richmond, B.C., was published online by a regional Chinese police bureau as early as 2020.

The revelation that the minister in charge of Canada’s intelligence and security agencies was only briefed about the issue in the past year raises a number of questions.

Were the agencies unaware of this open-source information, and only learned about this Chinese Communist Party (CCP) threat at the same time as the media, after NGO Safeguard Defenders released a report on the overseas stations in September 2022?

Or if the agencies were aware, did they decide not to brief the minister? This is an issue of such significance that, after coming to the public’s attention, was raised by Canada’s prime minister with China’s leader, and led to Global Affairs Canada summoning the Chinese ambassador multiple times for an explanation.

Phil Gurski, a veteran of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), says there could be another possibility.

“[Third] possibility: CSIS did brief senior officials, but this was not passed on to the minister for fear of upsetting Canada-PRC [People’s Republic of China] relations,” Gurski said in an email.

Scott McGregor, a former Canadian Armed Forces intelligence operator who also served as an intelligence adviser to the RCMP, says he’s confident Canada’s security agencies have been aware of these overseas police operations for years.

But he says the issue didn’t get government attention for the same reason that many other threats from China go unaddressed: lack of political will.

“What are you allowed to do about it? If you don’t have the resources, the laws will not allow you to enforce anything, so no one’s going to jail,” McGregor, who is now a private investigator and founder of Close Hold Intelligence, said in an interview.

“Are there laws that could be used? Certainly. But you’d have to have the support of the government in order to pursue those things, and because the government is so heavily invested and influenced, there is no political will.”

Trend

McGregor says he observed this reluctance to take on issues related to China first-hand in the mid-2010s when he was working in law enforcement in B.C., where there are major CCP-linked fentanyl-trafficking and money laundering operations through casinos and real estate transactions, driving the province’s rampant opioid crisis.

“We attempted to provide information that would go to the minister [of finance of B.C.] on what was happening with transnational organized crime and its connection to the Chinese, etc., and it was stonewalled,” he says.

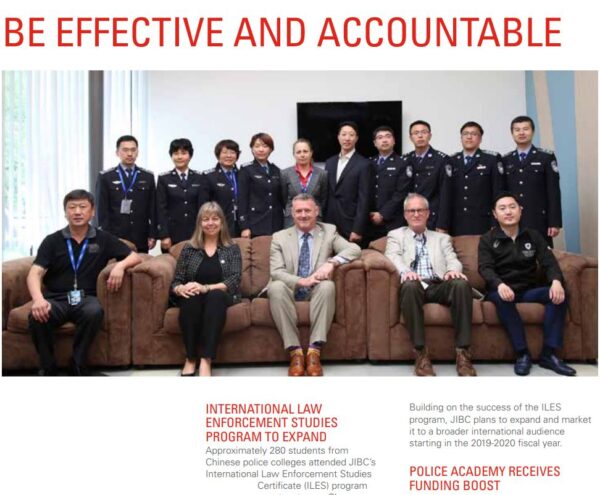

When it comes to the issue of Chinese police, McGregor says Canada’s naivete on the issue is best characterized by how the Justice Institute of British Columbia (JIBC) partnered with China’s Public Security Bureau to train Chinese police in the province beginning early last decade. The program was ended in 2019.

“Why are you training the Chinese police? They have a 99 percent conviction rate. Their laws are not congruent to ours,” he says.

“You’re accepting money from an authoritarian government to train their police in our methodologies, when you know that their espionage and collection of intelligence targets all aspects of our society in an effort to undermine it.”

McGregor says this is yet another example of the senior ranks of security agencies knowing such a program was wrong, yet it was allowed to proceed because they “don’t think there’s anything they can do about it.”

The Epoch Times contacted JIBC but the organization said it would need a week or two to comment.

Gurski concurs there’s a general sense in the intelligence community that there exists an unwillingness within the political class to deal with the China threat.

“CSIS has been warning about this for 25–30 years. We’re talking about Chinese theft of Canadian technology, we’re talking about interference in distinct communities,” he writes.

“We were ignored, because they saw the Chinese economic relationship as more important.”

A joint report by the RCMP and CSIS in 1997 titled Project Sidewinder, which was leaked to the media, warned about the CCP’s infiltration, influence, and espionage operations in Canada through means such as using criminal gangs and business tycoons. A 2000 publication by the Security Intelligence Review Committee, the governmental body that oversaw the operations of CSIS back then, dismissed the concerns raised in the Sidewinder report, saying, it “found no evidence of any substantial and immediate threat” as warned about in the report.

Minister Briefing

The RCMP announced in October 2022 that it was investigating the overseas Chinese police stations in Canada.

So far, the force has publicly confirmed the presence of four such stations in Canada. Safeguard Defenders says it is aware of five of them.

RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki told MPs at a Feb. 6 hearing of the House of Commons Special Committee on Canada-China Relations that uniformed officers have visited the four confirmed stations in Canada so that the public can see the “visible presence” of police, which she says would lead to the public sharing more information with the RCMP.

On Feb. 7, Conservative public safety critic Raquel Dancho questioned why no one “has been expelled or arrested” so far.

“Canadians need to know they are safe from foreign intimidation and threats within Canada,” she said on Twitter.

The Netherlands and Ireland both ordered the closure of unofficial Chinese police stations in their countries shortly after reports about them were made public. The FBI also shut down a station in New York at an undisclosed time following a reported raid last fall.

Conservative MP Garnett Genuis also questions why action hasn’t already been taken on the file. Minister Mendicino’s revelation at the Feb. 6 committee meeting on when he learned about the overseas stations was in response to a question from Genuis.

“Ministers are responsible for seeking the information they need from their teams. It may be that the [issue] only came to his attention through media reports, or it may be that he was told about it earlier. But still, [it was] within the last year, in which case it begs the question why wasn’t action taken on this earlier,” Genius told The Epoch Times.

“Either way, it’s a problem. Did he not have information he needed to do this job? Or did he not act on that information early enough?”

The Epoch Times contacted the Public Safety department and Mendicino’s office for comment, but didn’t hear back by publication time.

During their Feb. 6 exchange, Genuis asked Mendicino if he learned about the police stations before or after media reports about them emerged. Mendicino replied that he became “generally aware of this particular subject matter within the last year.”

Genius says his take on the exchange is that the minister didn’t want to answer the question because “the existence of these police stations is a clear problem, and hasn’t been addressed up until now.”

A CSIS spokesperson told The Epoch Times that it can’t “confirm or deny” information about specific briefings, adding that the agency routinely talks with elected officials on security issues.

“CSIS engages with elected officials at all levels of government (federal, provincial/territorial, municipal, and Indigenous), to raise awareness of the potential threats to the security and interests of Canada,” Brandon Champagne said in an email.

Transnational Threats

McGregor says uniformed RCMP officers showing up at the Chinese police stations in Canada is only a measure to appease the public and make it look like law enforcement is taking some action to restore public confidence. But he says the public is becoming more aware of the lack of action.

“The public is becoming much more savvy,” he says.

Besides the lack of political will, McGregor says, another major shortcoming in Canada is the lack of a security strategy to address transnational crime.

“The majority of the intelligence files leading to arrests, such as the major transnational narcoterrorist cases, are from our neighbour [the United States],” he says.

“The entities that collect all of this data and share it, and whom we’re relying on for understanding what’s going on in our own country, aren’t even Canadian.”