Why Credit and Inflation Are Highly Uncertain

Commentary U.S. inflation is coming down, but there are various reasons for this. Market analysts tend to follow the majority of views that the overall number is lowered by energy-related items. Official academics like those working for the Fed tend to find evidence for supply-side arguments. They employ the old structural equation models to decompose the shocks into demand versus supply and conclude. Yet this approach has been criticized since the 1970s (the previous inflationary episode) for missing an important element of monetary policy expectations. Had the supply side been the main true reason, the Fed (and other central banks) would not have to hike rates in such an aggressive manner because the shortage of goods can only be solved by producing more instead of raising borrowing costs. They did so, implying they admitted the demand side argument wholeheartedly. It is the central bankers who invented the concept of a non-inflationary rate of unemployment (NAIRU), which implies the limit of monetary easing that is not leading to employment overheating. Now the limit is exceeded. Inflation, measured by the consumer price index (CPI) or personal consumption expenditures (PCE) deflator, is defined by the consumption price. Thus, consumer credit growth is a close proxy for inflation. Credit growth is hard to predict because central banks can control the interest rate and monetary base directly but not borrowing or lending. It is the latter, together with savings, that constitute the broad money. Now the question comes: Does tightening reduce credit growth effectively? This is crucial in telling whether inflation is contained. U.S. Interest Rate, Money and Credit, YoY % Change. Jan. 30, 2023. (Courtesy of Law Ka-chung) The accompanying chart shows the consumer credit with M2 and Fed funds rate, all in year-over-year change. M2 is not the same as credit as the former is composed of savings while the latter is lending, where the two are not necessarily equal. In exceptional times like 2008 and 2020, it could be M2 (savings) growing fast while credit (lending) crunching. From the latest data, one can see now it is the opposite: M2 is shrinking while credit growth is speeding. This means the interest rate is still not high enough to attract savings and discourage lending. Another observation is that if having Fed funds rate leading two years in the design of the chart, then it is quite correlated with consumer credit (both in YoY change). The reason is also intuitive, as borrowers would pay only attention to the costs of borrowing rather than anything else like M2 growth. However, a two-year time lag is long enough for policymakers to act wrongly, either over or underdone. For consumer credit to fall (negative growth), a two percent YoY rate hike is needed (compare the vertical axes). It is unclear if a four percent credit fall suffices to bring inflation back to two percent. Examining the experience in the mid-1970s, it took much longer than two years from a rate hike to a credit growth slowdown. Admittedly, there are numerous factors other than the interest rate driving credit. This is probably why inflation is so unpredictable, even nowadays, with rich models and data. Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.

Commentary

U.S. inflation is coming down, but there are various reasons for this. Market analysts tend to follow the majority of views that the overall number is lowered by energy-related items. Official academics like those working for the Fed tend to find evidence for supply-side arguments. They employ the old structural equation models to decompose the shocks into demand versus supply and conclude. Yet this approach has been criticized since the 1970s (the previous inflationary episode) for missing an important element of monetary policy expectations.

Had the supply side been the main true reason, the Fed (and other central banks) would not have to hike rates in such an aggressive manner because the shortage of goods can only be solved by producing more instead of raising borrowing costs. They did so, implying they admitted the demand side argument wholeheartedly. It is the central bankers who invented the concept of a non-inflationary rate of unemployment (NAIRU), which implies the limit of monetary easing that is not leading to employment overheating. Now the limit is exceeded.

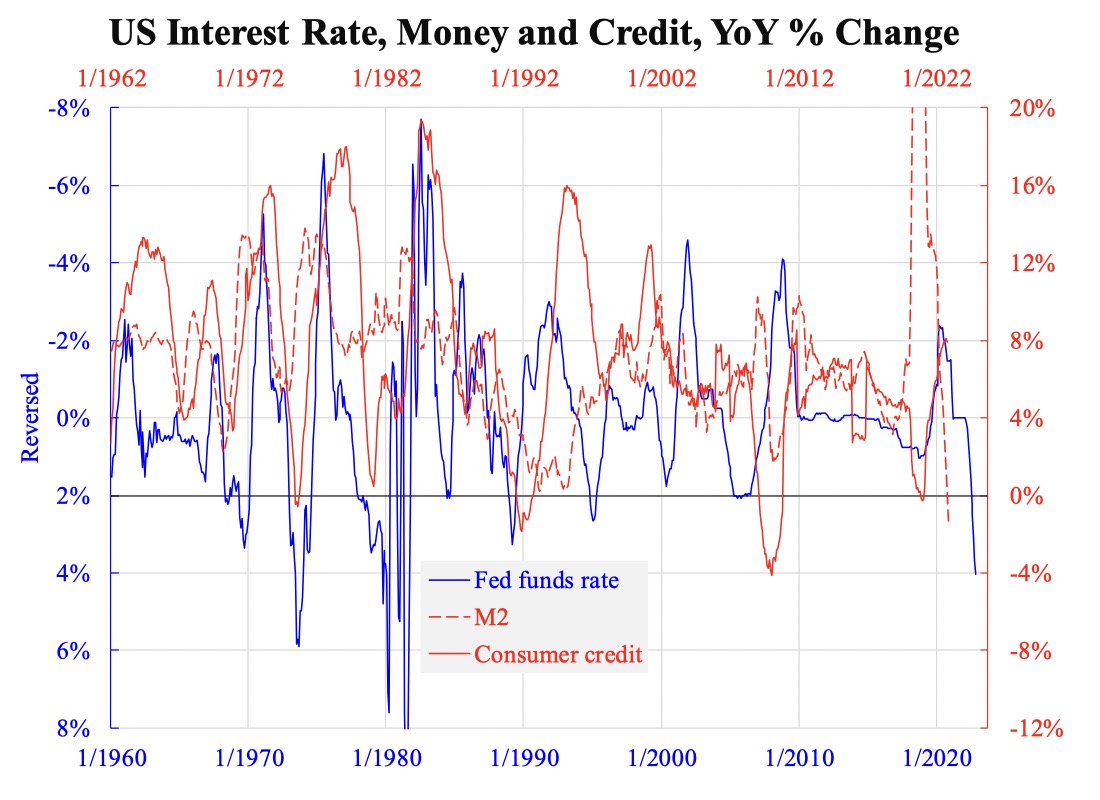

Inflation, measured by the consumer price index (CPI) or personal consumption expenditures (PCE) deflator, is defined by the consumption price. Thus, consumer credit growth is a close proxy for inflation. Credit growth is hard to predict because central banks can control the interest rate and monetary base directly but not borrowing or lending. It is the latter, together with savings, that constitute the broad money. Now the question comes: Does tightening reduce credit growth effectively? This is crucial in telling whether inflation is contained.

The accompanying chart shows the consumer credit with M2 and Fed funds rate, all in year-over-year change. M2 is not the same as credit as the former is composed of savings while the latter is lending, where the two are not necessarily equal. In exceptional times like 2008 and 2020, it could be M2 (savings) growing fast while credit (lending) crunching. From the latest data, one can see now it is the opposite: M2 is shrinking while credit growth is speeding. This means the interest rate is still not high enough to attract savings and discourage lending.

Another observation is that if having Fed funds rate leading two years in the design of the chart, then it is quite correlated with consumer credit (both in YoY change). The reason is also intuitive, as borrowers would pay only attention to the costs of borrowing rather than anything else like M2 growth. However, a two-year time lag is long enough for policymakers to act wrongly, either over or underdone. For consumer credit to fall (negative growth), a two percent YoY rate hike is needed (compare the vertical axes). It is unclear if a four percent credit fall suffices to bring inflation back to two percent.

Examining the experience in the mid-1970s, it took much longer than two years from a rate hike to a credit growth slowdown. Admittedly, there are numerous factors other than the interest rate driving credit. This is probably why inflation is so unpredictable, even nowadays, with rich models and data.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.