Indigenous Land Rights Under Threat by Lula’s Presidential Victory

CommentaryOn Nov. 8, about 500 Brazilian Indians of the Paresi tribe from the mid-western state of Mato Grosso, arrived in Brasília, Brazil’s federal capital. They were there to join the massive protests against the victory of the far-left candidate, Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, in last month’s presidential elections. Irisnaide Silva is the female Indigenous leader of the Macuxi tribe—one of two main indigenous groups in the Amazonian state of Roraima. For once, she says, a Brazilian president has finally bothered to hear her. The Indigenous leader has met several times with the present incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, to discuss a bill that would authorise mining on indigenous lands. For decades she and her family picked and panned their land, scouring the hills for diamonds and gold. However, when Lula da Silva became the nation’s president, his government made it illegal to mine in her indigenous territory despite protests from her tribe. She is not alone in her appreciation for Bolsonaro. According to Carpejane Lima, another female Indigenous leader, “The importance of mining not only for my community but for the others is also the development it is bringing …. Those who didn’t own a car, now do. Those who didn’t have a house are now building one.” Of course, as one may expect, many global green activists have accused these Indigenous leaders of being traitors. “I’ve been called a white Indian,” Silva told Reuters over squawking chickens at her modest home in the indigenous community’s reserve. She doesn’t care. “We always appreciated that, dressing well, eating well, having a car. This has been evolving, today we are looking for that. If we can dress better and better, we will do it,” she says. Indigenous Lands Are Rich and Fertile According to data from the National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI) there are approximately 900,000 indigenous persons (0.5 percent of the national population), representing 305 distinct ethnic groups and 274 languages. Over 500,000 of them live in 4,774 villages spread over 505 formally recognised indigenous lands covering 13 percent of the national territory. The amount of land classified as belonging to the Indigenous peoples is larger than the territory of any European nation, bar Russia. These indigenous lands are regarded as the permanent possession of the Brazilian Indians. They should have total control over all the riches of their soil, rivers, and lakes. This appears to be wonderful were it not for the following problem: only the federal legislature (National Congress) can authorize the utilization of mineral riches in these lands. As a result, Bolsonaro said in a January 2019 meeting with Indigenous leaders: “Our Indians, most of them, are condemned to live in poverty.” President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro arrives for a press conference two days after being defeated by Lula da Silva in the presidential runoff at Alvorada Palace in Brasilia, Brazil, on Nov. 1, 2022. (Andressa Anholete/Getty Images) Bolsonaro has always advocated for the basic right of Indigenous peoples to mining and utilization of natural resources in their native territories. In his assessment, the vast territory belonging to the Indigenous peoples has been underutilised by their constitutional owners due to environmental policies carried out by left-wing governments with the support of global green NGOs. “You have a lot of land. Let’s use this land … Are [you] going to remain poor? Being enslaved by NGOs?” Bolsonaro asked Indigenous leaders in January 2019. “Some people want you to remain on indigenous territories like prehistoric animals. Under the soil, you have billions or trillions of dollars,” he added. On March 18, Bolsonaro was awarded the medal for “Indigenous Merit,” a distinction bestowed on personalities who have stood for the wellbeing of the Indigenous peoples. The award is an honour created in 1972 by the Ministry of Justice. Bolsonaro was deemed worthy of receiving the accolade “in recognition of the relevant services of altruistic character, related to the welfare, protection, and defence of indigenous communities.” On that occasion, he reminded that “no other government in Brazil’s history has ever come closest to the Indigenous peoples and wanted them to do with their lands exactly what we do with ours,” drawing applause from the crowd. At the end of that ceremony, representatives of various Indigenous communities insisted on participating in a historic photo with the president. Not surprisingly, the award angered many radical environmentalists. Apparently, the end of these NGOs’ influence over the Amazon region was a primary cause for such indignation. History Shows Lula Doesn’t Choose What’s Best for the Indigenous Peoples Those NGOs strongly supported Lula’s return to the presidency, despite, according to an article in the Texas International Law Review published in the first year of his administration, “rule of law problems, political pressures on the executive a

Commentary

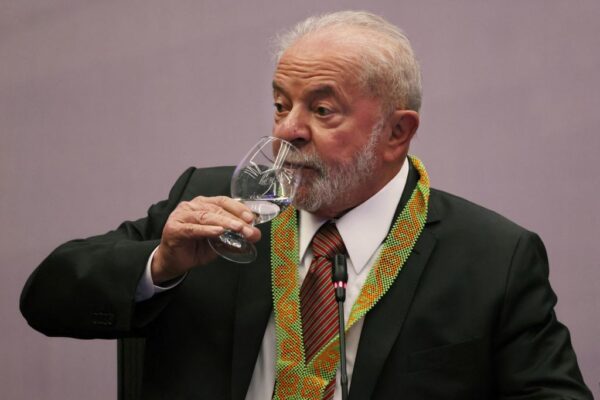

On Nov. 8, about 500 Brazilian Indians of the Paresi tribe from the mid-western state of Mato Grosso, arrived in Brasília, Brazil’s federal capital. They were there to join the massive protests against the victory of the far-left candidate, Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, in last month’s presidential elections.

Irisnaide Silva is the female Indigenous leader of the Macuxi tribe—one of two main indigenous groups in the Amazonian state of Roraima. For once, she says, a Brazilian president has finally bothered to hear her.

The Indigenous leader has met several times with the present incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, to discuss a bill that would authorise mining on indigenous lands. For decades she and her family picked and panned their land, scouring the hills for diamonds and gold. However, when Lula da Silva became the nation’s president, his government made it illegal to mine in her indigenous territory despite protests from her tribe.

She is not alone in her appreciation for Bolsonaro. According to Carpejane Lima, another female Indigenous leader, “The importance of mining not only for my community but for the others is also the development it is bringing …. Those who didn’t own a car, now do. Those who didn’t have a house are now building one.”

Of course, as one may expect, many global green activists have accused these Indigenous leaders of being traitors.

“I’ve been called a white Indian,” Silva told Reuters over squawking chickens at her modest home in the indigenous community’s reserve. She doesn’t care.

“We always appreciated that, dressing well, eating well, having a car. This has been evolving, today we are looking for that. If we can dress better and better, we will do it,” she says.

Indigenous Lands Are Rich and Fertile

According to data from the National Indigenous Foundation (FUNAI) there are approximately 900,000 indigenous persons (0.5 percent of the national population), representing 305 distinct ethnic groups and 274 languages. Over 500,000 of them live in 4,774 villages spread over 505 formally recognised indigenous lands covering 13 percent of the national territory.

The amount of land classified as belonging to the Indigenous peoples is larger than the territory of any European nation, bar Russia.

These indigenous lands are regarded as the permanent possession of the Brazilian Indians. They should have total control over all the riches of their soil, rivers, and lakes.

This appears to be wonderful were it not for the following problem: only the federal legislature (National Congress) can authorize the utilization of mineral riches in these lands. As a result, Bolsonaro said in a January 2019 meeting with Indigenous leaders: “Our Indians, most of them, are condemned to live in poverty.”

Bolsonaro has always advocated for the basic right of Indigenous peoples to mining and utilization of natural resources in their native territories. In his assessment, the vast territory belonging to the Indigenous peoples has been underutilised by their constitutional owners due to environmental policies carried out by left-wing governments with the support of global green NGOs.

“You have a lot of land. Let’s use this land … Are [you] going to remain poor? Being enslaved by NGOs?” Bolsonaro asked Indigenous leaders in January 2019.

“Some people want you to remain on indigenous territories like prehistoric animals. Under the soil, you have billions or trillions of dollars,” he added.

On March 18, Bolsonaro was awarded the medal for “Indigenous Merit,” a distinction bestowed on personalities who have stood for the wellbeing of the Indigenous peoples. The award is an honour created in 1972 by the Ministry of Justice.

Bolsonaro was deemed worthy of receiving the accolade “in recognition of the relevant services of altruistic character, related to the welfare, protection, and defence of indigenous communities.”

On that occasion, he reminded that “no other government in Brazil’s history has ever come closest to the Indigenous peoples and wanted them to do with their lands exactly what we do with ours,” drawing applause from the crowd.

At the end of that ceremony, representatives of various Indigenous communities insisted on participating in a historic photo with the president.

Not surprisingly, the award angered many radical environmentalists. Apparently, the end of these NGOs’ influence over the Amazon region was a primary cause for such indignation.

History Shows Lula Doesn’t Choose What’s Best for the Indigenous Peoples

Those NGOs strongly supported Lula’s return to the presidency, despite, according to an article in the Texas International Law Review published in the first year of his administration, “rule of law problems, political pressures on the executive as well as on the judiciary, and societal attitudes … contributed to a hostile environment for indigenous peoples” during that period.

During the long Lula administration from 2003 to 2011, about half of all the Brazilian Indians were condemned to live under conditions of extreme poverty, completely reliant on a federal program of basic food baskets to survive.

They also faced extremely poor health care, and the government’s own medical department estimated that in those days, around 60 percent of all the Indians in Brazil suffered from chronic diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria, and hepatitis.

As reported by Freedom House, a non-profit, majority U.S. government-funded organization, under the Lula administration, Brazilian Indians suffered from all sorts of human rights violations, including epidemic disease, forced labour, violent death, and marginalisation.

Despite that appalling record, many NGOs recently took to social media to celebrate the return of Lula’s presidency and end of Bolsonaro’s.

“There is now hope that the situation will improve for the indigenous communities in Brazil and the protection of the environment,” stated Julia Büsser, campaign manager for the NGO Society for Threatened Peoples.

In reality, the first era of Lula’s presidency left a dark legacy concerning policies that negatively affected the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, and this is likely to continue with his return. In April, as a presidential candidate, Lula promised to reverse all the government plans to allow the Indigenous peoples commercial agriculture, mining and oil exploration on their own native lands.

In other words, this newly re-elected politician has vowed to entirely reverse Bolsonaro’s policies for the development of Indigenous rights over their own native land.

And since what Lula promises basically amounts to a constitutional violation of the property rights of the Indigenous people, we must conclude that the outcome of this recent election in Brazil raises serious doubts about the future of the nation’s Indigenous peoples, particularly those living in the Amazon.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.