Wishes, Blame, and an Excruciating Death

CommentaryWhen Queen Elizabeth II, 96 years old, was close to death, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University called Uju Anya, whose areas of inquiry include “applied linguistics as a practice of social justice and translanguaging in world language pedagogy,” published her desire that the Queen should die an excruciating death. Surprisingly for someone who thought it fit to utter so vile a sentiment in public, Anya looks rather a nice person. Of course, someone can look nice without being nice, but in all probability she is, in general, a nice person. What, then, caused her to emerge from her obscurity into the light of publicity with her unpleasant outburst? The short answer is adherence to ideology and dishonest abstract ideas. She justified her sentiment by reference to the Nigerian Civil War in which her father’s family suffered—she herself was born six years after it ended. The war occurred when the Igbo people, or the government of eastern Nigeria, tried to break away from the federal state of Nigeria and form an independent state of Biafra. The war caused starvation and much death in eastern Nigeria, but the federal side prevailed, having received aid from Britain and other countries. Anya seems to blame Elizabeth II for the suffering of the people in eastern Nigeria, but she has let her emotion and her ignorance run away with her. If the British government of the day had sided with Biafra, or indeed remained neutral, the Queen would not have intervened, for she had nothing to do with the formation of policy. Anya calls her the “chief monarch,” a rather odd expression demonstrating a firm lack of understanding of constitutional monarchy as practiced in Britain, in short ignorance. One might as well blame the Supreme Court for the Vietnam War or the withdrawal from Afghanistan, or any other act of American foreign policy. But there is more. Until his death, I was a friend of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian writer, whom I used to see on my visits to Port Harcourt, and on his to London. He wrote an anti-war masterpiece titled “Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English,” which was an account, in semi-pidgin English, by a naïve young boy who finds himself fighting on both sides in the war without knowing why he is fighting for either, except that he first proudly donned a uniform to impress his girlfriend, who ultimately is killed. After a page or two, you grasp the language in which it is written; it is an eloquent protest against the horror of war. It ends with a moving declaration, through the mouth of the novel’s protagonist and narrator: “And I was thinking how I was prouding before to go to soza and call myself Sozaboy [soldier boy]. But now if anybody say anything about war or even fight, I will just run and run and run and run and run. Believe me yours sincerely.” Now, Saro-Wiwa was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority group in Igboland. He thought, rightly or wrongly is beside the point, that the Ogoni people would fare better in a federal Nigeria than in an independent Biafra, and therefore actively supported the federal military effort. Presumably, Anya would have wished him an excruciating death because he was far more plausibly or directly responsible for what was done in the war than was the Queen. If so, she would have had her wish. Long after the war, Saro-Wiwa started a movement for the compensation of the Ogoni people for the virtual destruction of their ancestral homeland by oil production, the control of whose revenues was the most important prize in Nigerian politics. I tried to persuade him not to go into politics—I thought Nigeria needed writers more than it needed yet more politicians, and he was talented—but he did not heed my pleas because he said the situation of his people was so dire. And he predicted that the government would eventually kill him. I thought he was exaggerating: The Nigerian government was bad but not murderous at the time. However, he was right: He was arrested on a trumped-up charge, tried in a kangaroo court, and sentenced to hang. Apparently, it took five goes to hang him, and he said, “In this country, they can’t even hang a man properly.” So Anya would have got her wish for an excruciating death for Saro-Wiwa. For myself, I wish no person such a death, and I hardly dare add that I wish it least of all for a man who had his faults no doubt, as all of us do, but whom I esteemed highly. There is another point to be made, and that is that, in making Queen Elizabeth a scapegoat for the Nigerian Civil War, Anya is turning Africans into less than full adults who are not really responsible for what they do. On the contrary, they are the puppets of all-powerful others, who can and do manipulate them any way they wish. The history of post-colonial Africa is replete (rather less so now, thank goodness) with political monsters. Among the worst was Macias Nguema, the first president of Equatorial Guinea, until his nephew, who is still president 43 years

Commentary

When Queen Elizabeth II, 96 years old, was close to death, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University called Uju Anya, whose areas of inquiry include “applied linguistics as a practice of social justice and translanguaging in world language pedagogy,” published her desire that the Queen should die an excruciating death.

Surprisingly for someone who thought it fit to utter so vile a sentiment in public, Anya looks rather a nice person. Of course, someone can look nice without being nice, but in all probability she is, in general, a nice person.

What, then, caused her to emerge from her obscurity into the light of publicity with her unpleasant outburst? The short answer is adherence to ideology and dishonest abstract ideas.

She justified her sentiment by reference to the Nigerian Civil War in which her father’s family suffered—she herself was born six years after it ended. The war occurred when the Igbo people, or the government of eastern Nigeria, tried to break away from the federal state of Nigeria and form an independent state of Biafra. The war caused starvation and much death in eastern Nigeria, but the federal side prevailed, having received aid from Britain and other countries.

Anya seems to blame Elizabeth II for the suffering of the people in eastern Nigeria, but she has let her emotion and her ignorance run away with her. If the British government of the day had sided with Biafra, or indeed remained neutral, the Queen would not have intervened, for she had nothing to do with the formation of policy. Anya calls her the “chief monarch,” a rather odd expression demonstrating a firm lack of understanding of constitutional monarchy as practiced in Britain, in short ignorance. One might as well blame the Supreme Court for the Vietnam War or the withdrawal from Afghanistan, or any other act of American foreign policy.

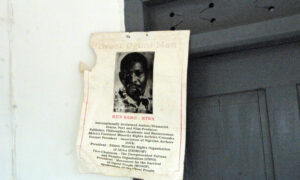

But there is more. Until his death, I was a friend of Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Nigerian writer, whom I used to see on my visits to Port Harcourt, and on his to London. He wrote an anti-war masterpiece titled “Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English,” which was an account, in semi-pidgin English, by a naïve young boy who finds himself fighting on both sides in the war without knowing why he is fighting for either, except that he first proudly donned a uniform to impress his girlfriend, who ultimately is killed. After a page or two, you grasp the language in which it is written; it is an eloquent protest against the horror of war. It ends with a moving declaration, through the mouth of the novel’s protagonist and narrator:

“And I was thinking how I was prouding before to go to soza and call myself Sozaboy [soldier boy]. But now if anybody say anything about war or even fight, I will just run and run and run and run and run. Believe me yours sincerely.”

Now, Saro-Wiwa was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority group in Igboland. He thought, rightly or wrongly is beside the point, that the Ogoni people would fare better in a federal Nigeria than in an independent Biafra, and therefore actively supported the federal military effort. Presumably, Anya would have wished him an excruciating death because he was far more plausibly or directly responsible for what was done in the war than was the Queen.

If so, she would have had her wish. Long after the war, Saro-Wiwa started a movement for the compensation of the Ogoni people for the virtual destruction of their ancestral homeland by oil production, the control of whose revenues was the most important prize in Nigerian politics. I tried to persuade him not to go into politics—I thought Nigeria needed writers more than it needed yet more politicians, and he was talented—but he did not heed my pleas because he said the situation of his people was so dire. And he predicted that the government would eventually kill him.

I thought he was exaggerating: The Nigerian government was bad but not murderous at the time. However, he was right: He was arrested on a trumped-up charge, tried in a kangaroo court, and sentenced to hang. Apparently, it took five goes to hang him, and he said, “In this country, they can’t even hang a man properly.”

So Anya would have got her wish for an excruciating death for Saro-Wiwa. For myself, I wish no person such a death, and I hardly dare add that I wish it least of all for a man who had his faults no doubt, as all of us do, but whom I esteemed highly.

There is another point to be made, and that is that, in making Queen Elizabeth a scapegoat for the Nigerian Civil War, Anya is turning Africans into less than full adults who are not really responsible for what they do. On the contrary, they are the puppets of all-powerful others, who can and do manipulate them any way they wish.

The history of post-colonial Africa is replete (rather less so now, thank goodness) with political monsters. Among the worst was Macias Nguema, the first president of Equatorial Guinea, until his nephew, who is still president 43 years later, overthrew him in a military coup. Macias killed or drove into exile a third of the population of a country that had once been thriving; he left it destitute, starving, and utterly destroyed.

Of course, Anya would ascribe this (and all the other monstrous things done by Sekou Touré, the Emperor Bokassa, Idi Amin, et al.) to the legacy of colonialism, but this is in effect to say that when Macias killed his enemies, kept the national treasury under his bed, and executed people for possessing a page of print, he did not know what he was doing: He was really an infant. And this is precisely what an unreconstructed racist would say.

Then, of course, it might be alleged that Nigeria and other countries were not “natural” nations and were the result of a European carve-up that lumped different peoples together. This is true, but irrelevant: Nigeria has so many different ethnic groups that no modern state could have been formed without amalgamation. Moreover, some of the states that were more or less “natural”—Burundi, Rwanda, Somalia—have fared among the worst.

Anya’s remarks are a mixture of crudity and ignorance, combined with an uncontrolled and not altogether ungratifying (for her) sense of rage. She does not think clearly: But then, would one expect someone among whose specialties is “applied linguistics as a practice of social justice and translanguaging in world language pedagogy”?

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.