While the US Starts Countering Fox Hunt and Chinese Policing Abroad, Europe Lags Far Behind

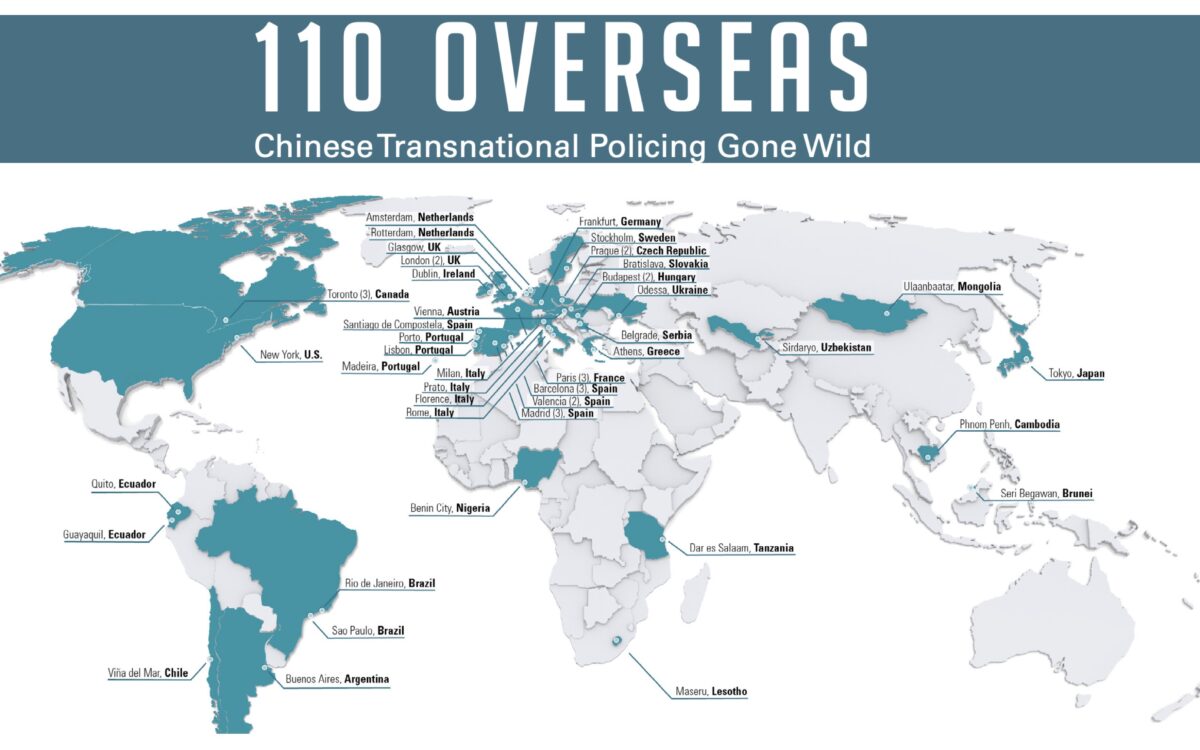

CommentaryWhile the FBI and the Department of Justice are starting to act against Chinese long-arm policing, especially the global Fox Hunt operation, its allies lag far behind, and no other country has moved to have any indictments made. Europe, in particular, is letting Fox Hunt run rampant and without pushback. On Oct. 20 and 24, the Department of Justice unsealed two new indictments against China’s Fox Hunt operations on U.S. (and Canadian) soil, after their first one back in 2020. Then on Oct. 27, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “anti-corruption” watchdog released its annual work report at the Party Congress, which, taken together with prior reports, showed that the Fox Hunt operation has now surpassed some 11,000 successful cases from 120 countries. Fox Hunt claims to work to repatriate escaped fugitives, or those wanted for prosecution, especially higher-value targets such as former Party members, state functionaries, or those from state-owned enterprises who stand accused of corruption or embezzlement. In reality, the campaign was launched not long after CCP leader Xi Jinping’s domestic “anti-corruption” campaign, which seems more intent on being a tool for political purges than punishing economic crimes. Fox Hunt is a tool that sends one very clear message: leaving or escaping China, no matter where you go, will not make you safe nor protect you—resistance is futile. FBI Director Christopher Wray speaks during a virtual news conference at the Department of Justice in Washington on Oct. 28, 2020. – Five Chinese agents were arrested in the United States for their role in an operation targeting opponents of the Chinese regime. Then-Assistant Attorney General John Demers said charges had been filed against eight people involved in an “illegal Chinese law enforcement operation known as Fox Hunt.” (Sarah Silbiger/AFP via Getty Images) Some imagine that China would engage in the mass use of extraditions, the regular judicial procedure for such work, but that is far from the truth. In 2018, for example, only 17 cases, out of more than 1,335 successful returns, were via extraditions. Most extraditions are via “involuntary returns,” including sending agents abroad to harass and intimidate victims on-site. This is the case in all three indictments in the United States. And remarkably, those indictments show multi-year operations, with teams of operatives running the show in China and the United States, and extensive travel between the two countries of both teams. As seen in the indictments, these operations have largely failed. So one can only imagine how many are being undertaken if 11,000 have already been successful. On top of that, the targets are often well-off and unlikely to decamp in places like Cambodia or Pakistan but rather seek out the United States, Canada, Western Europe, or Australia. Sheer statistics indicate these campaigns are all around us, and they know no borders. Yet, until now, European allies have failed to take action against a single one. Security services are, historically, hesitant to bring information about such operations into the open, and even more so in bringing about formal investigations and prosecutions. Instead, they treat it like a political issue and often let China off the hook. The United States had also done this, like when Ministry of State Security agents were caught visiting tycoon and political activist Guo Wengui in New York. This silence only encourages more of the same. At the National Congress in October this year, Beijing announced its intention to expand its Fox Hunt operation and tie it more closely to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as “One Belt, One Road”). France is a case in point. French security service DGSI was already aware, by the time Safeguard Defenders published a major report on Fox Hunt and its methods used almost a year ago, of two such operations in France. Since then, French police have offered Grace Meng and her two children around-the-clock protection, lending credence to the claim of the wife of the disappeared and later imprisoned former Chinese INTERPOL chief, of attempts to kidnap or harass her in France. Overseas Chinese police “Service Stations,” or “110 Overseas,” are found in dozens of countries across five continents. (Courtesy of Safeguard Defenders) Now, with Safeguard Defenders’ latest investigation, it has become clear, using Chinese State media as a source, that one of the many overseas police “service stations” set up in France—without knowledge of the French government—has been used to launch a “persuasion” campaign against a Chinese resident in Paris whom Beijing wanted to be returned. The head of the station—run by the Wenzhou police on China’s eastern coast and located in the Parisian suburb of Aubervilliers—claims to have worked with police from Wenzhou to have the target returned, and bragged about it in Chinese state media in late 2021. It has already been exposed that such “service stat

Commentary

While the FBI and the Department of Justice are starting to act against Chinese long-arm policing, especially the global Fox Hunt operation, its allies lag far behind, and no other country has moved to have any indictments made. Europe, in particular, is letting Fox Hunt run rampant and without pushback.

On Oct. 20 and 24, the Department of Justice unsealed two new indictments against China’s Fox Hunt operations on U.S. (and Canadian) soil, after their first one back in 2020. Then on Oct. 27, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “anti-corruption” watchdog released its annual work report at the Party Congress, which, taken together with prior reports, showed that the Fox Hunt operation has now surpassed some 11,000 successful cases from 120 countries.

Fox Hunt claims to work to repatriate escaped fugitives, or those wanted for prosecution, especially higher-value targets such as former Party members, state functionaries, or those from state-owned enterprises who stand accused of corruption or embezzlement. In reality, the campaign was launched not long after CCP leader Xi Jinping’s domestic “anti-corruption” campaign, which seems more intent on being a tool for political purges than punishing economic crimes. Fox Hunt is a tool that sends one very clear message: leaving or escaping China, no matter where you go, will not make you safe nor protect you—resistance is futile.

Some imagine that China would engage in the mass use of extraditions, the regular judicial procedure for such work, but that is far from the truth. In 2018, for example, only 17 cases, out of more than 1,335 successful returns, were via extraditions. Most extraditions are via “involuntary returns,” including sending agents abroad to harass and intimidate victims on-site.

This is the case in all three indictments in the United States. And remarkably, those indictments show multi-year operations, with teams of operatives running the show in China and the United States, and extensive travel between the two countries of both teams.

As seen in the indictments, these operations have largely failed. So one can only imagine how many are being undertaken if 11,000 have already been successful. On top of that, the targets are often well-off and unlikely to decamp in places like Cambodia or Pakistan but rather seek out the United States, Canada, Western Europe, or Australia. Sheer statistics indicate these campaigns are all around us, and they know no borders.

Yet, until now, European allies have failed to take action against a single one. Security services are, historically, hesitant to bring information about such operations into the open, and even more so in bringing about formal investigations and prosecutions. Instead, they treat it like a political issue and often let China off the hook. The United States had also done this, like when Ministry of State Security agents were caught visiting tycoon and political activist Guo Wengui in New York. This silence only encourages more of the same. At the National Congress in October this year, Beijing announced its intention to expand its Fox Hunt operation and tie it more closely to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as “One Belt, One Road”).

France is a case in point. French security service DGSI was already aware, by the time Safeguard Defenders published a major report on Fox Hunt and its methods used almost a year ago, of two such operations in France. Since then, French police have offered Grace Meng and her two children around-the-clock protection, lending credence to the claim of the wife of the disappeared and later imprisoned former Chinese INTERPOL chief, of attempts to kidnap or harass her in France.

Now, with Safeguard Defenders’ latest investigation, it has become clear, using Chinese State media as a source, that one of the many overseas police “service stations” set up in France—without knowledge of the French government—has been used to launch a “persuasion” campaign against a Chinese resident in Paris whom Beijing wanted to be returned. The head of the station—run by the Wenzhou police on China’s eastern coast and located in the Parisian suburb of Aubervilliers—claims to have worked with police from Wenzhou to have the target returned, and bragged about it in Chinese state media in late 2021. It has already been exposed that such “service stations” in Spain and Serbia have likewise been engaged in similar actions, with the case in Serbia being a Fox Hunt target.

Yet, despite multiple instances of such gross violations of national and judicial sovereignty by China, France kept mum, refusing to take action, launch formal investigations, or reach out for assistance. It seems France, like many European allies, intends to keep silent on the issue, hoping that silence will make the problem disappear—not realizing perhaps that it invites more, not less, such violations and intrusions. The European leaders’ failure to take action leaves the significant Chinese diaspora across Europe exposed and with little protection; without protection, their ability to use their democratic rights and freedoms is curtailed.

The Chinese regime considers Europe so weak that it doesn’t even bother to try to explain its behavior away. In the case of Spain when the Chinese foreign ministry was asked about the case that took place in Madrid, it simply said that extraditions are “cumbersome” and don’t always work in Europe (even though Spain extradites more people to China than any other European nation) and that it, therefore, had to use other methods to get their wanted targets back.

Chinese authorities have issued similar statements but often more general, and most often targeting the United States and Canada, which have refused to enter into extradition agreements with China. This statement, specifically in response to a particular country and case—a country that has extradition cooperation with China—was outrageous, but it caused little alarm in Madrid and other capitals around Europe.

The United States should be applauded for having changed tack in how to deal with China’s Fox Hunt operations and other methods used to intimidate or harass Chinese nationals in their country. But the real tipping point will be if European countries can get their act together and commit real resources to tackle such operations.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.