US Needs Tougher Laws Against Federal Stock Traders

CommentaryThe U.S. federal government has over 1.8 million civilian employees and over 1.3 million active duty military personnel. Many have access to confidential information that could be traded in the stock market to give an edge against taxpayer stock traders who pay their salaries. That’s just wrong. A major Wall Street Journal study, published in a series of investigative articles this month, delves into the details of questionable stock trades and conflicts of interest by mostly mid-level officials in the executive branch. The Journal found that laws for public disclosure and recusal from policymaking on issues that would affect their investments are often not complied with and seldom enforced. When enforced, the penalties are typically a slap on the wrist relative to what the federal stock traders, for lack of a better term, can make in the markets. One of the most interesting findings is that Department of Defense officials are among the largest investors, relative to other federal officials, in Chinese stocks. “Across the federal government, more than 400 officials owned or traded Chinese company stocks, including officials at the State Department and White House,” according to the Journal. “Their investments amounted to between $1.9 million and $6.6 million on average a year.” Reed Werner, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for South and Southeast Asia, reported purchasing as much as $50,000 of Alibaba stock in December 2020. Deliberations were ongoing at the time about whether to bar Americans from investing in Alibaba. Werner was involved in the discussions, according to a Journal source. The Treasury Department decided not to ban Alibaba; that day, its stock value rose 4 percent. Three days later, according to Werner’s disclosure form, he sold Alibaba stock. That was good timing; as the next day, there were more deliberations about whether to add Alibaba to the blacklist. The logo for Alibaba Group is seen on the trading floor at the New York Stock Exchange in Manhattan, New York, on Aug. 3, 2021. (Andrew Kelly/Reuters) Despite these dubious-sounding trades, ethics officials at the Pentagon certified that Reed was in compliance with the law. The appearance of a conflict of interest and access to confidential information that could be traded on, therefore, was not Reed’s fault but a weakness in the law itself. The most senior official covered by the investigation is former Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao. On March 16, 2020, the S&P 500 index of the biggest U.S. stocks fell 12 percent, pressured by worries about the effect of the pandemic on the economy. That day, Chao purchased as much as $1.2 million worth of funds that track U.S. stocks broadly. Three days later, Chao’s husband, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, released the first draft of his economic stimulus legislation, signed on March 27, 2020, by then-President Donald Trump. Chao and McConnell got pens at the signing. The S&P soared 57 percent by the end of 2020; presumably, so did the family investment. Whether or not Chao had advance knowledge of the stimulus funding, and whether that influenced her decision to invest in the S&P, is unknown. But it does give the appearance of impropriety and, therefore, should never be allowed by an official who holds the public trust. Again, the problem is a lack of effective legislation, not Chao’s actions that were within the bounds of a weak law. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), left, and his wife, Elaine Chao, along with Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), in the background, attend services at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington on Jan. 20, 2021. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images) The challenge goes beyond a couple of examples. U.S. officials often hold stocks in companies that lobby them, creating the unacceptable appearance of a conflict of interest. “Across 50 federal agencies ranging from the Commerce Department to the Treasury Department, more than 2,600 officials reported stock investments in companies while those companies were lobbying their agencies for favorable policies, during both Republican and Democratic administrations,” according to the Journal. “When the financial holdings caused a conflict, the agencies sometimes simply waived the rules.” Over 200 senior Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials and their family members, for example, collectively owned as much as $2 million in oil and gas stocks from 2016 to 2021, on average. Department of Defense officials in the office of the secretary, and their family members, jointly owned as much as $3.4 million in aerospace and defense stocks during the same period. “More than five dozen officials at five agencies reported trading stocks of companies shortly before their departments announced enforcement actions against those companies, such as charges or settlements,” according to the Journal. “While the government was ramping up scrutiny of large

Commentary

The U.S. federal government has over 1.8 million civilian employees and over 1.3 million active duty military personnel. Many have access to confidential information that could be traded in the stock market to give an edge against taxpayer stock traders who pay their salaries. That’s just wrong.

A major Wall Street Journal study, published in a series of investigative articles this month, delves into the details of questionable stock trades and conflicts of interest by mostly mid-level officials in the executive branch. The Journal found that laws for public disclosure and recusal from policymaking on issues that would affect their investments are often not complied with and seldom enforced.

When enforced, the penalties are typically a slap on the wrist relative to what the federal stock traders, for lack of a better term, can make in the markets.

One of the most interesting findings is that Department of Defense officials are among the largest investors, relative to other federal officials, in Chinese stocks.

“Across the federal government, more than 400 officials owned or traded Chinese company stocks, including officials at the State Department and White House,” according to the Journal. “Their investments amounted to between $1.9 million and $6.6 million on average a year.”

Reed Werner, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for South and Southeast Asia, reported purchasing as much as $50,000 of Alibaba stock in December 2020. Deliberations were ongoing at the time about whether to bar Americans from investing in Alibaba. Werner was involved in the discussions, according to a Journal source.

The Treasury Department decided not to ban Alibaba; that day, its stock value rose 4 percent. Three days later, according to Werner’s disclosure form, he sold Alibaba stock. That was good timing; as the next day, there were more deliberations about whether to add Alibaba to the blacklist.

Despite these dubious-sounding trades, ethics officials at the Pentagon certified that Reed was in compliance with the law. The appearance of a conflict of interest and access to confidential information that could be traded on, therefore, was not Reed’s fault but a weakness in the law itself.

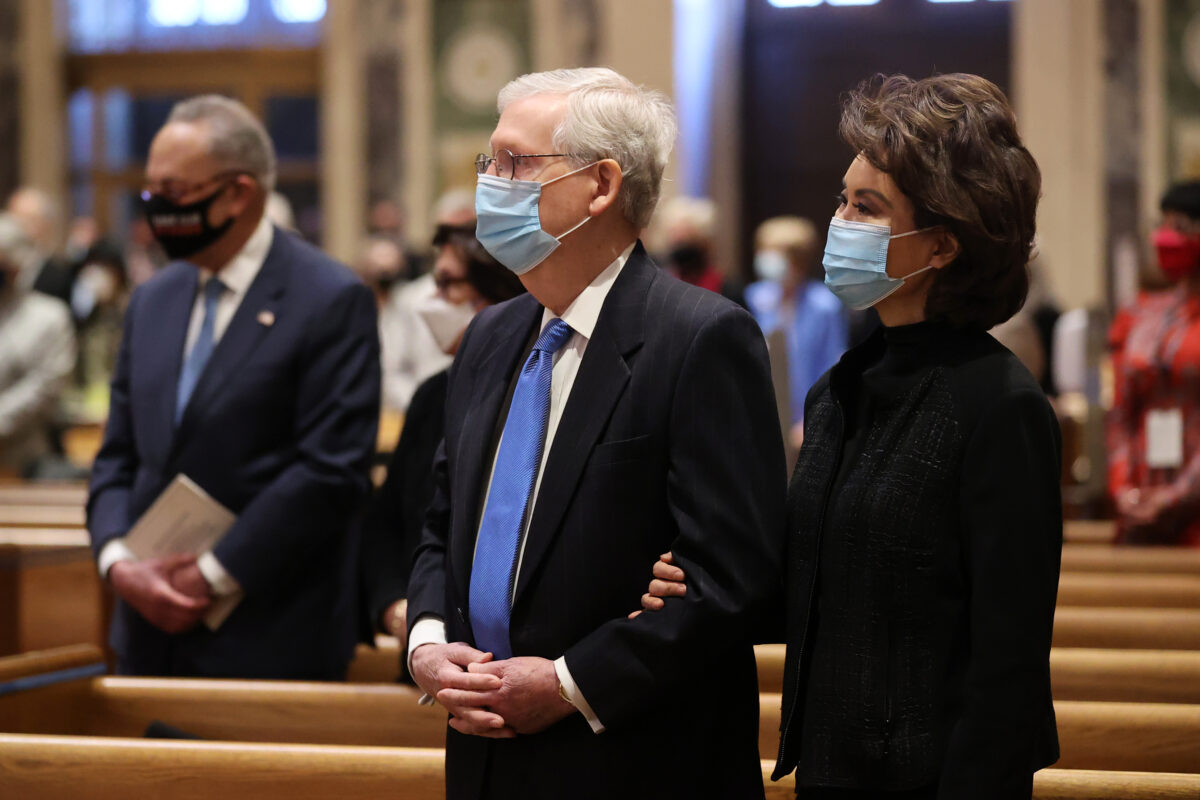

The most senior official covered by the investigation is former Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao. On March 16, 2020, the S&P 500 index of the biggest U.S. stocks fell 12 percent, pressured by worries about the effect of the pandemic on the economy. That day, Chao purchased as much as $1.2 million worth of funds that track U.S. stocks broadly.

Three days later, Chao’s husband, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, released the first draft of his economic stimulus legislation, signed on March 27, 2020, by then-President Donald Trump. Chao and McConnell got pens at the signing.

The S&P soared 57 percent by the end of 2020; presumably, so did the family investment. Whether or not Chao had advance knowledge of the stimulus funding, and whether that influenced her decision to invest in the S&P, is unknown. But it does give the appearance of impropriety and, therefore, should never be allowed by an official who holds the public trust.

Again, the problem is a lack of effective legislation, not Chao’s actions that were within the bounds of a weak law.

The challenge goes beyond a couple of examples. U.S. officials often hold stocks in companies that lobby them, creating the unacceptable appearance of a conflict of interest.

“Across 50 federal agencies ranging from the Commerce Department to the Treasury Department, more than 2,600 officials reported stock investments in companies while those companies were lobbying their agencies for favorable policies, during both Republican and Democratic administrations,” according to the Journal.

“When the financial holdings caused a conflict, the agencies sometimes simply waived the rules.”

Over 200 senior Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials and their family members, for example, collectively owned as much as $2 million in oil and gas stocks from 2016 to 2021, on average.

Department of Defense officials in the office of the secretary, and their family members, jointly owned as much as $3.4 million in aerospace and defense stocks during the same period.

“More than five dozen officials at five agencies reported trading stocks of companies shortly before their departments announced enforcement actions against those companies, such as charges or settlements,” according to the Journal.

“While the government was ramping up scrutiny of large technology companies, more than 1,800 federal officials reported owning or trading at least one of four major tech stocks: Meta Platforms Inc.’s Facebook, Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Apple Inc., and Amazon.com Inc.”

It’s great when our government officials believe and invest in America. But there should be no appearance of trading on confidential information or a conflict of interest in their policy deliberations. American officials should be focused on their privilege to serve the American people in their official jobs and not wasting their time through stock trading, for which the U.S. taxpayer pays, both in terms of the official’s salary, and the loss of stock value against federal traders with confidential information and influence over policy.

As a government official, yes, buy into America in its broadest sense. Yes, allow your financial adviser to make decisions without your input. But do not make trades yourself, especially not in areas where you hold power as an official. That power, and the information that comes with it, is a privilege delegated to you by the American people, and it should not be traded away for personal benefit.

Human nature being what it is, we cannot expect our officials to follow these ethical principles out of the goodness of their hearts. Tougher laws must be legislated. But as the example of the Chao-McConnell family shows, the fox is guarding the chicken coop.

Therefore, Americans need to make noise and take to the streets until our legislators get motivated to do the right thing and limit government officials from playing the markets. Taxpayers should no longer accept the appearance of self-serving corruption in our government.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.