‘This Is My Family’: An American’s Story Defending Freedom in China and US

For 54 years, China wasn’t on Gail Rachlin’s radar. Then, in the fall of 1997, it entered her life unexpectedly.At a health expo at New York City’s Javits Center, she was looking for business opportunities and health solutions for herself and noticed a young man at a booth. A former public relations (PR) executive, she had moved on to running her own PR business. She was good at reading people, and his energy stood out to her. “What do you sell?” she walked up to him, thinking it was vitamin pills. “No,” the man laughed, “This is free.” “Nothing’s free in New York!” she replied. Sure enough, the young man taught her an exercise of Falun Gong, free of charge. Also known as Falun Dafa, Falun Gong is an ancient belief rooted in the traditional Chinese culture of Buddhism and Taoism. It’s based on the tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance and features a set of five slow-moving meditative exercises. A Falun Gong group exercise site in Changchun, Jilin Province, China, in 1998. (Courtesy of Gail Rachlin) Immediately, Rachlin felt a surge of energy in her body. So she learned more of the exercises and took up the practice. An ovarian cancer survivor since 29, she had been looking for alternative health practices. A few months later, Rachlin was diagnosed with breast cancer. In a choice between having surgery and doing the Falun Gong exercises, she chose the latter. Two months later, her doctor confirmed that a malignant lump had shrunk to less than a quarter in size and wasn’t a concern anymore. Soon afterward, she fully recovered. “I became a real believer because it was just amazing,” Rachlin, now 79, told The Epoch Times, referring to the spiritual practice. Together with another seven women, all Chinese Americans, who went to Riverside Park at 105th Street to do the Falun Gong exercises together, she began promoting the practice locally. Trip to Beijing and Changchun In August 1998, a friend got Rachlin a contract to visit Beijing to try to attract Chinese businesses to an expo at the World Trade Center in New York City. For that purpose, she had meetings with Chinese officials in Beijing. During the first week of her visit, when she and three officials were chatting about working out, Rachlin said, “I do exercises, too!” “It was my first time meeting Chinese communist government [officials]. I told them I was practicing—I just started the year before—Falun Gong, and they all looked at each other, literally froze,” she recalled. “I was very proud. I didn’t realize anything; nobody had said anything to me before,” she added. “As the naïve American, I mentioned I was practicing [Falun Gong], and my wonderful health changes.” After some awkward silence, one official with the English name Bill said he practiced qigong too for quite a few years. Then, the group changed topics. Rachlin at the time didn’t know then that many people in China were drawn to the healing effect of qigong—physical and breathing exercises connected to traditional Chinese culture—in the 1980s and 1990s. Qigong was a fad in Chinese society. Li Hongzhi, the founder of Falun Gong, introduced the practice to the public in 1992 as a form of qigong. By 1998, Falun Gong had become the most popular qigong known to the Chinese population. By July 1999, official estimates placed the number of adherents at 70 million to 100 million. The following week, she said she sensed a heightened curiosity from the Chinese officials as they arranged for her to tour some Chinese manufacturing factories: “They were all looking at me, like, what is she doing here? What is she going to do?” It wasn’t until later during the trip that she understood why. Rachlin took a side trip to Changchun, the capital of Jilin Province in northeast China, for a personal reason: the city is the hometown of Falun Gong’s founder, where the practice spread through word of mouth. There, she participated in group exercises; she estimated that there were 2,000 people at one park and 5,000 in another. “I was blown away,” she said, comparing the number to her local group of eight in Manhattan. Gail Rachlin (2nd L) with Chinese Falun Gong practitioners in Changchun, Jilin Province, China, in 1998. (Courtesy of Gail Rachlin) Falun Gong adherents in Changchun were amazed to know that an American shared their belief. At Jilin University, she met some and had tea with them. They chatted through her interpreter. She still remembers some of the stories that the Chinese Falun Gong practitioners shared with her. One resonated with her deeply. A woman, 65, a retired medical professional, said her doctor had told her five years ago that she had only six months to live. After that, she took up Falun Gong and thought that if she was going to die, she might as well be spiritual and peaceful. Rachlin specifically remembered that she used the word “peaceful.” The woman said she survived her terminal illness because of Falun Gong. Rachlin still remembered that the w

For 54 years, China wasn’t on Gail Rachlin’s radar. Then, in the fall of 1997, it entered her life unexpectedly.

At a health expo at New York City’s Javits Center, she was looking for business opportunities and health solutions for herself and noticed a young man at a booth. A former public relations (PR) executive, she had moved on to running her own PR business.

She was good at reading people, and his energy stood out to her.

“What do you sell?” she walked up to him, thinking it was vitamin pills.

“No,” the man laughed, “This is free.”

“Nothing’s free in New York!” she replied.

Sure enough, the young man taught her an exercise of Falun Gong, free of charge. Also known as Falun Dafa, Falun Gong is an ancient belief rooted in the traditional Chinese culture of Buddhism and Taoism. It’s based on the tenets of truthfulness, compassion, and forbearance and features a set of five slow-moving meditative exercises.

Immediately, Rachlin felt a surge of energy in her body. So she learned more of the exercises and took up the practice. An ovarian cancer survivor since 29, she had been looking for alternative health practices.

A few months later, Rachlin was diagnosed with breast cancer. In a choice between having surgery and doing the Falun Gong exercises, she chose the latter. Two months later, her doctor confirmed that a malignant lump had shrunk to less than a quarter in size and wasn’t a concern anymore. Soon afterward, she fully recovered.

“I became a real believer because it was just amazing,” Rachlin, now 79, told The Epoch Times, referring to the spiritual practice.

Together with another seven women, all Chinese Americans, who went to Riverside Park at 105th Street to do the Falun Gong exercises together, she began promoting the practice locally.

Trip to Beijing and Changchun

In August 1998, a friend got Rachlin a contract to visit Beijing to try to attract Chinese businesses to an expo at the World Trade Center in New York City.

For that purpose, she had meetings with Chinese officials in Beijing. During the first week of her visit, when she and three officials were chatting about working out, Rachlin said, “I do exercises, too!”

“It was my first time meeting Chinese communist government [officials]. I told them I was practicing—I just started the year before—Falun Gong, and they all looked at each other, literally froze,” she recalled.

“I was very proud. I didn’t realize anything; nobody had said anything to me before,” she added. “As the naïve American, I mentioned I was practicing [Falun Gong], and my wonderful health changes.”

After some awkward silence, one official with the English name Bill said he practiced qigong too for quite a few years. Then, the group changed topics.

Rachlin at the time didn’t know then that many people in China were drawn to the healing effect of qigong—physical and breathing exercises connected to traditional Chinese culture—in the 1980s and 1990s. Qigong was a fad in Chinese society.

Li Hongzhi, the founder of Falun Gong, introduced the practice to the public in 1992 as a form of qigong. By 1998, Falun Gong had become the most popular qigong known to the Chinese population. By July 1999, official estimates placed the number of adherents at 70 million to 100 million.

The following week, she said she sensed a heightened curiosity from the Chinese officials as they arranged for her to tour some Chinese manufacturing factories:

“They were all looking at me, like, what is she doing here? What is she going to do?”

It wasn’t until later during the trip that she understood why.

Rachlin took a side trip to Changchun, the capital of Jilin Province in northeast China, for a personal reason: the city is the hometown of Falun Gong’s founder, where the practice spread through word of mouth. There, she participated in group exercises; she estimated that there were 2,000 people at one park and 5,000 in another.

“I was blown away,” she said, comparing the number to her local group of eight in Manhattan.

Falun Gong adherents in Changchun were amazed to know that an American shared their belief. At Jilin University, she met some and had tea with them. They chatted through her interpreter. She still remembers some of the stories that the Chinese Falun Gong practitioners shared with her.

One resonated with her deeply.

A woman, 65, a retired medical professional, said her doctor had told her five years ago that she had only six months to live. After that, she took up Falun Gong and thought that if she was going to die, she might as well be spiritual and peaceful. Rachlin specifically remembered that she used the word “peaceful.” The woman said she survived her terminal illness because of Falun Gong.

Rachlin still remembered that the woman had short gray hair. But at the roots, an inch was black.

“Can you imagine all the roots were black? It was her hair growing,” she said.

“I was like, ‘What happened with that? What is this?’

“And she said, ‘I think I’m doing better.’ She was so cute,” Rachlin recalled.

In Changchun, other Falun Gong adherents warned Rachlin to “be careful.” They told her that police had been showing unusual interest in the group lately by frequently appearing at exercises in public parks and questioning different practitioners. She recalled the conversation with the Chinese communist officials and understood why Bill later asked her in private her reason for practicing Falun Gong.

After six weeks in China, Rachlin returned to New York without securing any Chinese visitors to the expo. She realized years later that mentioning Falun Gong may have partially contributed to that outcome.

Things Get Personal

Rachlin’s life returned to normal, and she continued to spread the word about Falun Gong in New York City. After news on April 25, 1999, that over 10,000 Falun Gong adherents had peacefully protested outside of the central Chinese Communist Party (CCP) compound in Beijing calling for an end to the regime’s escalated suppression of the practice, Rachlin started using her company to create videos and other materials to tell the Falun Gong’s side of the story.

The persecution, which began a few months later, swept the entire country. Many volunteer organizers of group exercise sites similar to the ones Rachlin had attended in Changchun were arrested overnight.

Having visited Changchun and knowing Falun Gong practitioners in China, it felt close to home.

“This is my family. How could anybody touch them? This is not right,” she said.

“So, it was a personal thing for me. It really was, and I’ve always felt that. I still do.”

Thus, given her professional PR background, she volunteered as a spokesperson for Falun Gong.

“I had no idea about China before. I didn’t know about the Cultural Revolution,” she said, referring to a period of great upheaval launched by the Party from 1966 to 1976 during which the country’s cultures and traditions were destroyed. “I read it maybe as a kid, but I was never a history major.

“World history-wise, it wasn’t a big deal because, as an American, I was interested in my country: red, white, and blue. And I wanted to find out what’s going on here. Not politically, but how do people live in Texas differently than in California?”

She added: “I didn’t think in the scope of China until I got involved with the practice and heard from some of my friends. What the Chinese practitioners went through there was devastating. I could not believe, as a Westerner, that the Chinese people live that way in China, being restricted.”

Persecution Hit Home

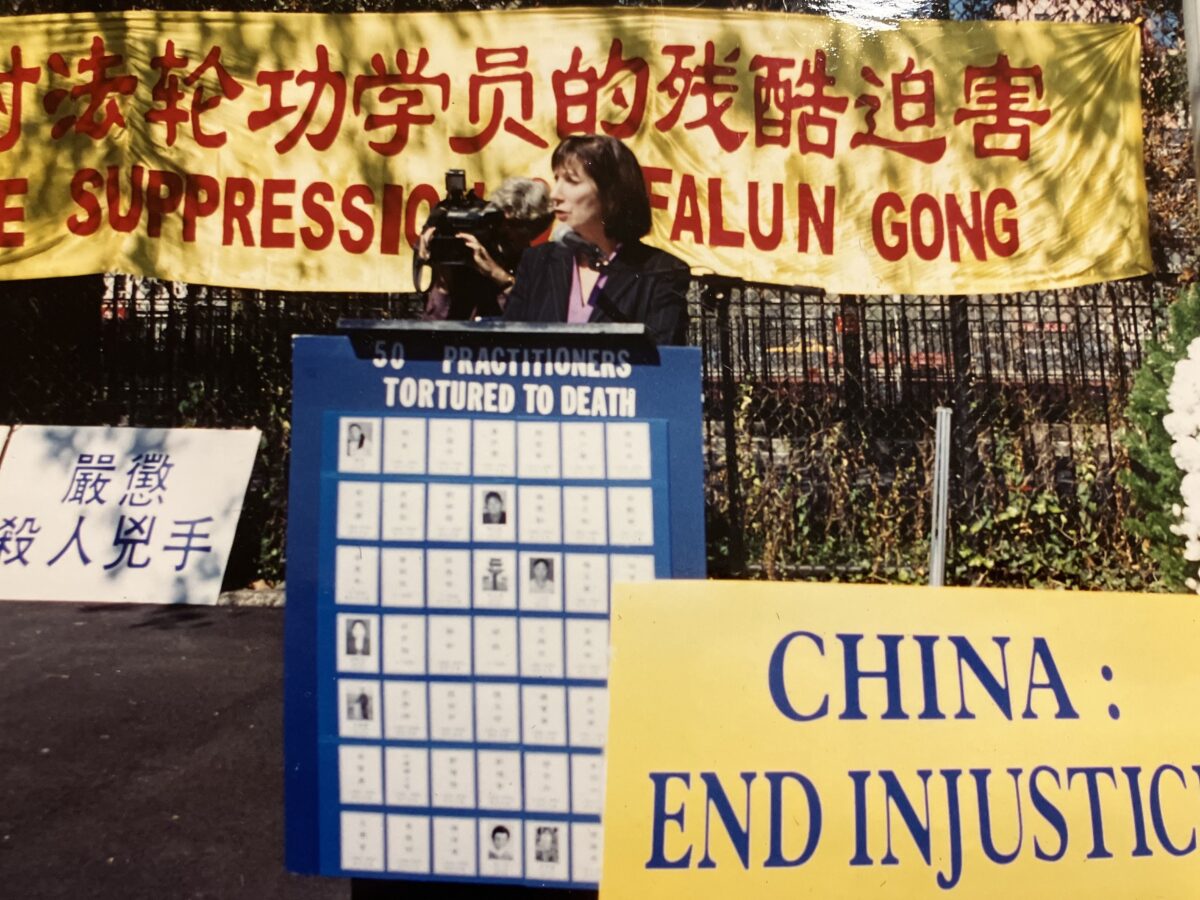

“My name is Gail Rachlin. Normally, when I stand up here, I’m a spokesperson for Falun Gong, but today, I’m a plaintiff in this case because I, too, have been violated by the Chinese government on American soil,” she read her statement outside the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in April 2002.

On April 3 of that year, more than 50 Falun Gong adherents in the United States, including Rachlin, filed a lawsuit against the Chinese Ministry of State Security, the regime’s intelligence agency, the Ministry of Public Security, the agency that oversees domestic security, and state-run broadcaster China Central Television for directing a “continuing criminal enterprise” of death threats, break-ins, beatings, arson, and wiretapping against them.

The lawsuit was based on the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), a law enacted in 1970 to address problems associated with organized crime.

For 16 years, Rachlin had lived in her apartment near Central Park and never had any incidents. However, between July and September in 1999, her home had three break-ins.

The first one occurred on July 25, 1999, days after the persecution began in China on July 20. When she got home, she saw the back door to the service entrance was left open, and a chain lock at the door was broken. While nothing seemed to have been taken, upon a careful search, she realized that tax records were taken from the top drawer of the filing cabinet in her home office.

Rachlin was shocked.

“Why would they [the CCP] try to do anything to me? I’m an American busy leading my life. And my meditation was just a part of it.”

The police couldn’t understand it either, she said.

“Every now and then, the police would check back because they couldn’t believe it. And a couple of them were shocked that China would be so bold. The Chinese Communist Party would be so bold as to do this,” she added.

The second time in August, she lost her address book. After that, she installed two locks on her front and back doors. The third time in September, the back door locks were broken, and the door was dented.

“The bottom line is that practitioners should be able to walk the streets of Washington like anybody else, and they can’t, simply because they are Falun Gong practitioners,” Martin McMahon, the lawyer representing the Falun Gong plaintiffs in the RICO lawsuit said in an interview in 2003.

For Rachlin, this was literally the case, except that it was in New York, not Washington.

In March 2000, after hosting a press conference inside the United Nations headquarters in Manhattan, she went to lunch a few blocks away with fellow Falun Gong spokesperson Erping Zhang. When they walked out of the restaurant after lunch, they saw a group of Chinese delegation members on the same sidewalk.

Rachlin said she could sense the hostility in the air as the officials were yelling at them in Chinese; Zhang told her to quickly cross the street to the other side and not look back.

As they were crossing the street, a Chinese delegation member threw rocks at them. Shortly after, the police stopped the rock thrower.

By August 2003, the CCP hadn’t responded to the RICO lawsuit. Instead, they sent a letter to the Department of Justice, asking the DOJ to “do something about the lawsuit,” according to McMahon, who said the DOJ shared the letter with him. The plaintiffs asked for a default judgment, which was denied on June 3, 2008, on the grounds of lack of evidence to substantiate the claim. According to Rachlin, it was difficult to prove that a contractual relationship existed between the CCP and the thugs who carried out the death threats, break-ins, beatings, arson, and wiretapping.

The RICO case was perhaps the first attempt in outlining and pushing back against the CCP’s transnational repression. The regime’s sprawling global campaign to surveil, harass, intimidate, and forcibly repatriate dissidents abroad has in recent years been more extensively documented.

In a 2021 report (pdf), Freedom House said that the CCP ran “the most sophisticated, global and comprehensive campaign of transnational repression in the world.” U.S. prosecutors have also brought several criminal cases against Chinese intelligence officers, officials, and Americans working with them in a series of alleged plots to surveil, harass, or forcibly repatriate dissidents living in the United States.

‘We Couldn’t Get Our Word Out’

While the persecution raged in China, overseas adherents also felt huge pressure due to the CCP’s aggressive efforts to wipe out international support for the practice.

“We must seize the opportunity of Western countries’ rising demand for us and push the related countries to ban or restrict the activities of the ‘Falun Gong’ … and strive to eliminate their long-term operational bases, sponsors, and partners,” so wrote a 2015 policy paper of the “610 Office” (pdf).

The “610 office” is a Gestapo-style body specializing in directing the persecution of Falun Gong. It got its name because it was established on June 10, 1999.

“The Office employs around 15,000 individuals across all Chinese and overseas territories” and its agents “act without any legal basis to eradicate the Falun Gong movement,” according to a 2021 report by the French Military School Strategic Research Institute, a think tank under the country’s military.

Several months into the persecution that officially began in July 1999, Rachlin started noticing fewer media reports on Falun Gong. For example, Mike Wallace of “60 Minutes” interviewed Falun Gong’s founder in Rachlin’s apartment in 1999, but the program wasn’t aired. Between late 1999 and early 2000, CNN followed her and Zhang for a day as they visited various Congressional offices; that program wasn’t aired. Another New York Times interview didn’t result in an article.

“This would happen not two, three times but five, eight times. And it was like, we couldn’t get our word out!” said Rachlin. “So, for me, it became so frustrating. The West, why don’t you get it? [Falun Gong] is something that is so good.”

“Nothing ever got published, nothing. This was the CCP, even back then,” she added.

It was not until much later that the regime’s efforts to influence and buy the silence of Western corporations were detailed by researchers and reporters.

A 2013 report (pdf) by the National Endowment for Democracy outlined the CCP’s transnational media controls. It said that the CCP used subtle influence methods in the form of “political and economic incentives” to “lead media owners and journalists to avoid topics likely to incur the CCP’s ire, especially commentary that challenges the legitimacy of one-party rule or reports that touch ‘hot button’ issues such as the plight of Tibetans, Uighurs, and Falun Gong practitioners.”

Global Lawsuits Against Jiang Zemin

As the persecution went underground in China, and the world seemed to have moved on with little news about Falun Gong, overseas adherents decided to go offensive. They aimed at the highest-ranking communist official responsible for ordering and directing the persecution: the then CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin (pdf).

Terri Marsh, executive director of the Human Rights Law Foundation (HRLF), spent over a decade trying to bring Jiang to justice worldwide. In October 2002, she filed a civil case against Jiang in the Eastern District Court in Illinois over crimes including genocide and crimes against humanity. Among the abuses listed in the suit were widespread torture, disappearances, forced labor, sexual crimes, and unlawful round-ups and detention.

This first lawsuit launched a legal wave against Jiang and his cohorts worldwide.

“I had hoped Jiang Zemin would survive long enough to become a defendant in a criminal case at a United Nations Tribunal or a Court in China for the crimes he perpetrated against Falun Gong believers, in addition to other dissident groups,” Marsh told The Epoch Times.

She was content, however, with the fact that the over 50 lawsuits filed globally against Jiang and his affiliates had kept the former leader “in effect in jail in China.” Jiang did not leave China over the past 20 years.

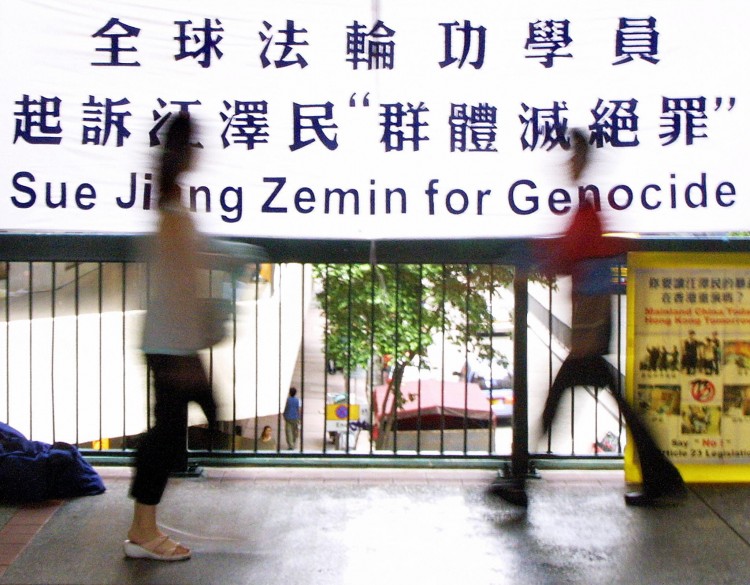

Residents walk past a protest banner supporting a lawsuit filed in Brussels against Chinese Communist Party head Jiang Zemin for genocide, on Aug. 30, 2003 in Hong Kong. (Laurent Fievet/AFP/Getty Images)

Residents walk past a protest banner supporting a lawsuit filed in Brussels against Chinese Communist Party head Jiang Zemin for genocide, on Aug. 30, 2003 in Hong Kong. (Laurent Fievet/AFP/Getty Images)

In November 2009, Jiang was indicted (pdf) in the Spanish national court for committing crimes of genocide and torture against Falun Gong. According to Marsh, the judge would have had Interpol take Jiang to Spain had the CCP not influenced Spain to change the law to disallow universal jurisdiction, which would have allowed the courts to try Jiang for crimes committed in China.

One month later, after four years of investigation, an Argentine federal judge asked Interpol to issue an arrest warrant for Jiang over torture and genocide against Falun Gong. Previously in April 2008, Judge Octavio de Lamadridheld held hearings with 17 Falun Gong witnesses testifying against Jiang at the Argentine consulate in New York.

Originally filed in December 2005, the case is still going on in Argentina. Lamadridheld resigned before Christmas of 2009. His interim successor immediately reversed the arrest warrant in January 2010 and closed the case. Falun Gong adherents appealed twice, the latest in April 2013 in the criminal court of appeal, the nation’s second-highest court, keeping the case active.

Marsh’s case was dismissed in September 2003 by a U.S. District Court judge in Chicago for lack of jurisdiction and sovereign immunity.

“The decision by our government to immunize Jiang Zemin as a head-of-state and literally defend him in federal court in Illinois is astonishing considering our government’s treatment of Saddam Hussein, another international criminal,” said Marsh.

States Lend Their Support

While the federal government may have stepped in to assist the former leader in a U.S. legal action, the states have acted differently.

In June, the attorneys general of 23 states wrote a joint amicus brief to the Supreme Court, urging it to hear a case brought by Falun Gong adherents against the Chinese Anti-Cult World Alliance (CACWA), a CCP front group operating in the United States.

The complaint (pdf) described around 40 incidents of threats or physical assault against Falun Gong adherents while participating in public activities raising awareness about the persecution, such as attending parades, handing out flyers on the street, or managing a Falun Gong information stand.

Flushing resident Edmond Erh was assaulted by a pro-CCP mob while supporting a booth for quitting the Chinese Communist Party in 2008. (Dayin Chen/The Epoch Times)

Flushing resident Edmond Erh was assaulted by a pro-CCP mob while supporting a booth for quitting the Chinese Communist Party in 2008. (Dayin Chen/The Epoch Times)

In one incident in July 2011, two plaintiffs described in graphic detail an attack orchestrated by Li Huahong, head of the CACWA. According to witnesses, at Li’s direction, a “backup” mob of 20 to 30 surrounded the two Falun Gong practitioners in Flushing, New York. One of them was held there for about 30 minutes until the police arrived, while the mob yelled, “kill her,” and “beat her to death.”

In their brief, the state attorneys general said that a lower court’s ruling dismissing the case is “wrong on an issue of national importance that stands at the center of our constitutional tradition”—namely, religious liberty.

“America’s commitment to religious freedom is ‘essential.’ … It constitutes ‘one of our most treasured and jealously guarded constitutional rights,’” the attorneys general wrote, quoting previous court opinions.

In October, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

The 23 states were West Virginia, Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia.

Then and Now

While the CCP’s influence operations and harassment of American citizens may have once been dismissed by the mainstream, such activities have received broader attention amid growing exposure and awareness of the Chinese regime’s malign actions both domestically and abroad.

“I think nowadays we can understand more what’s happening. Especially with the [zero-COVID] protests, people are waking up,” said Rachlin. “For me, back then, I felt our people [Falun Gong] were waking up, and they just wanted their freedom to meditate.”

She added that the facts of the persecution still needed to be brought out because now people would understand it.

“Now is the time that [the truth of the CCP] must come out so that people can understand who we are and welcome this practice into their hearts,” she said.

Rachlin will be 80 years old next year. Looking back on her life, she has never felt as positive as during the period after she started practicing Falun Gong, she said.

“Life would be tough or not tough, but I always got through—that’s the only way I could put it,” she said.

Rachlin spent the last 25 years of her life learning “what it means to put other things before yourself.”

“It sounded like a far-fetched idea. But when you put it in reality, it’s not. It’s a more wholesome way to live.”