The Economic Disaster of the Pandemic Response

CommentaryOn April 15, 2020, a full month after the President’s fateful news conference that greenlighted lockdowns to be enacted by the states for “15 Days to Flatten the Curve,” Donald Trump had a revealing White House conversation with Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease who had already become the public face of the COVID response. “I’m not going to preside over the funeral of the greatest country in the world,” Trump wisely said, as reported in Jared Kushner’s book “Breaking History.” Two weeks of lockdown was over and the promised Easter opening blew right by too, Trump was done. He also suspected that he had been misled and was no longer speaking to coronavirus coordinator Deborah Birx. “I understand,” Fauci responded meekly. “I just do medical advice. I don’t think about things like the economy and the secondary impacts. I’m just an infectious diseases doctor. Your job as president is to take everything else into consideration.” That conversation both reflected and entrenched the tone of the debate over the lockdowns and vaccine mandates and eventually the national crisis that they precipitated. In these debates in the early days, and even today, the idea of “the economy”—viewed as mechanistic, money-centered, mostly about the stock market, and detached from anything truly important—was pitted against public health and lives. You choose one or the other. You cannot have both. Or so they said. Pandemic Practice Also in those days, it was widely believed, stemming from a strange ideology hatched 16 years earlier, that the best approach to pandemics was to institute massive human coercion like we have never before experienced. The theory was that if you make humans behave like non-player characters in computer models, you can keep them from infecting each other until a vaccine arrives which will eventually wipe out the pathogen. The new lockdown theory stood in contrast to a century of pandemic advice and practice from public-health wisdom. Only a few cities tried coercion and quarantine to deal with the 1918 pandemic, mostly San Francisco (also the home of the first Anti-Mask League) whereas most just treated disease person by person. The quarantines of that period failed and so landed in disrepute. They were not tried again in the disease scares (some real, some exaggerated) of 1929, 1940–44, 1957–58, 1967–68, 2003, 2005, or 2009. In those days, even the national media urged calm and therapeutics during each infectious-disease scare. Somehow and for reasons that should be discussed—it could be intellectual error, political priorities, or some combination—2020 became the year of an experiment without precedent, not only in the United States but all over the world with the exception of perhaps five nations among which we can include the state of South Dakota. The sick and the well were quarantined, along with stay-at-home orders, domestic capacity limits, and business, school, and church shutdowns. Nothing turned out according to plan. The economy can be turned off using coercion but the resulting trauma is so great that turning it on again is not so easy. Instead, thirty months later, we face an economic crisis without precedent in our lifetimes, the longest period of declining real income in the post-war period, a health and educational crisis, an exploding national debt plus inflation at a 40-year high, continued and seemingly random shortages, dysfunction in labor markets that defies all models, the breakdown of international trade, a collapse in consumer confidence not seen since we have these numbers, and a dangerous level of political division. And what happened to COVID? It came anyway, just as many epidemiologists predicted it would. The stratified impact of medically significant outcomes was also predictable based on what we knew from February: the at-risk population was largely the elderly and infirmed. To be sure, most everyone would eventually met the pathogen with varying degrees of severity: some people shook it off in a couple of days, others suffered for weeks, and others perished. Even now, there is grave uncertainty about the data and causality due to the probability of misattribution due to both faulty PCR testing and financial incentives given out to hospitals. Tradeoffs Even if lockdowns had saved lives over the long term—the literature on this overwhelming suggests that the answer is no—the proper question to have asked was: at what cost? The economic question was: what are the tradeoffs? But because economics as such was shelved for the emergency, the question was not raised by policy makers. Thus did the White House on March 16, 2020, send out the most dreaded sentence pertaining to economics that one can imagine: “bars, restaurants, food courts, gyms, and other indoor and outdoor venues where groups of people congregate should be closed.” The results are legion. The lockdowns kicked off a whole range of other disastr

Commentary

On April 15, 2020, a full month after the President’s fateful news conference that greenlighted lockdowns to be enacted by the states for “15 Days to Flatten the Curve,” Donald Trump had a revealing White House conversation with Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease who had already become the public face of the COVID response.

“I’m not going to preside over the funeral of the greatest country in the world,” Trump wisely said, as reported in Jared Kushner’s book “Breaking History.” Two weeks of lockdown was over and the promised Easter opening blew right by too, Trump was done. He also suspected that he had been misled and was no longer speaking to coronavirus coordinator Deborah Birx.

“I understand,” Fauci responded meekly. “I just do medical advice. I don’t think about things like the economy and the secondary impacts. I’m just an infectious diseases doctor. Your job as president is to take everything else into consideration.”

That conversation both reflected and entrenched the tone of the debate over the lockdowns and vaccine mandates and eventually the national crisis that they precipitated. In these debates in the early days, and even today, the idea of “the economy”—viewed as mechanistic, money-centered, mostly about the stock market, and detached from anything truly important—was pitted against public health and lives.

You choose one or the other. You cannot have both. Or so they said.

Pandemic Practice

Also in those days, it was widely believed, stemming from a strange ideology hatched 16 years earlier, that the best approach to pandemics was to institute massive human coercion like we have never before experienced. The theory was that if you make humans behave like non-player characters in computer models, you can keep them from infecting each other until a vaccine arrives which will eventually wipe out the pathogen.

The new lockdown theory stood in contrast to a century of pandemic advice and practice from public-health wisdom. Only a few cities tried coercion and quarantine to deal with the 1918 pandemic, mostly San Francisco (also the home of the first Anti-Mask League) whereas most just treated disease person by person. The quarantines of that period failed and so landed in disrepute. They were not tried again in the disease scares (some real, some exaggerated) of 1929, 1940–44, 1957–58, 1967–68, 2003, 2005, or 2009. In those days, even the national media urged calm and therapeutics during each infectious-disease scare.

Somehow and for reasons that should be discussed—it could be intellectual error, political priorities, or some combination—2020 became the year of an experiment without precedent, not only in the United States but all over the world with the exception of perhaps five nations among which we can include the state of South Dakota. The sick and the well were quarantined, along with stay-at-home orders, domestic capacity limits, and business, school, and church shutdowns.

Nothing turned out according to plan. The economy can be turned off using coercion but the resulting trauma is so great that turning it on again is not so easy. Instead, thirty months later, we face an economic crisis without precedent in our lifetimes, the longest period of declining real income in the post-war period, a health and educational crisis, an exploding national debt plus inflation at a 40-year high, continued and seemingly random shortages, dysfunction in labor markets that defies all models, the breakdown of international trade, a collapse in consumer confidence not seen since we have these numbers, and a dangerous level of political division.

And what happened to COVID? It came anyway, just as many epidemiologists predicted it would. The stratified impact of medically significant outcomes was also predictable based on what we knew from February: the at-risk population was largely the elderly and infirmed. To be sure, most everyone would eventually met the pathogen with varying degrees of severity: some people shook it off in a couple of days, others suffered for weeks, and others perished. Even now, there is grave uncertainty about the data and causality due to the probability of misattribution due to both faulty PCR testing and financial incentives given out to hospitals.

Tradeoffs

Even if lockdowns had saved lives over the long term—the literature on this overwhelming suggests that the answer is no—the proper question to have asked was: at what cost? The economic question was: what are the tradeoffs? But because economics as such was shelved for the emergency, the question was not raised by policy makers. Thus did the White House on March 16, 2020, send out the most dreaded sentence pertaining to economics that one can imagine: “bars, restaurants, food courts, gyms, and other indoor and outdoor venues where groups of people congregate should be closed.”

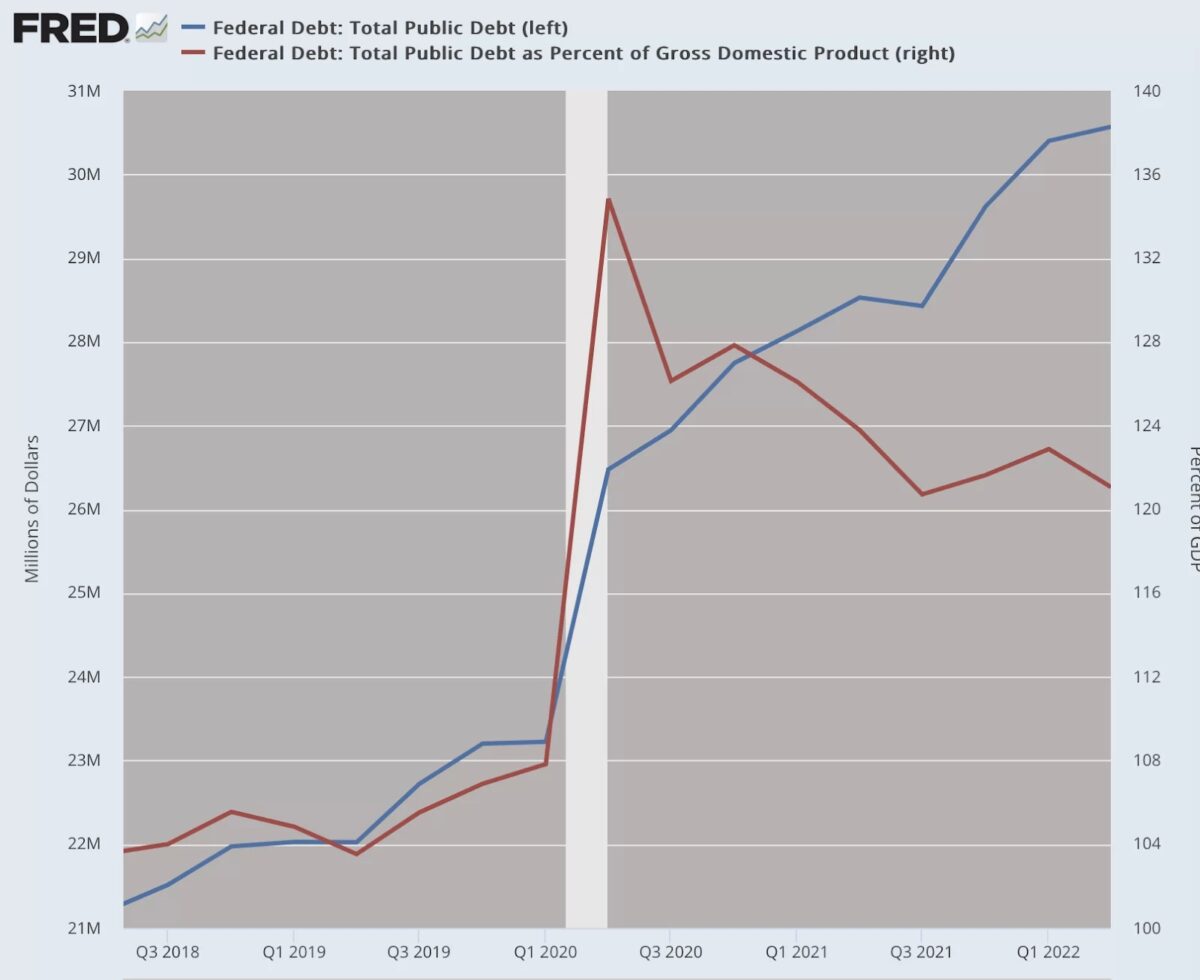

The results are legion. The lockdowns kicked off a whole range of other disastrous policy decisions, among which an epic bout of government spending. What we are left with is a national debt that is 121 percent of GDP. This compares to 35 percent of GDP in 1981 when Ronald Reagan correctly declared it a crisis. Government spending in the COVID response amounted to at least $6 trillion above normal operations, creating debt that the Federal Reserve purchased with newly created money nearly dollar for dollar.

Money Printing

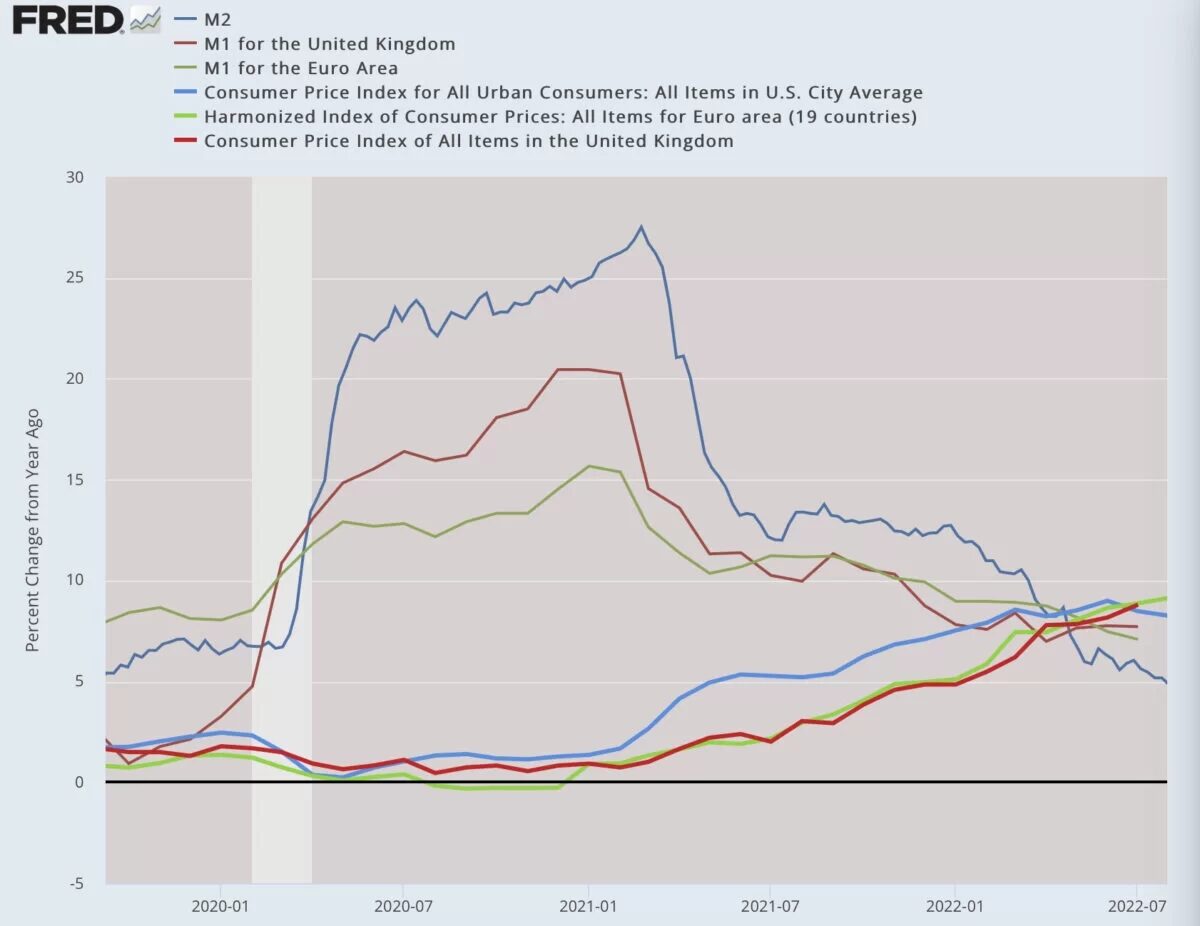

From February to May 2020, M2 increased by an average of $814.3 billion per month. On May 18, 2020, M2 was rising 22 percent year over year, compared with only 6.7 percent from March that year. It was not yet the peak. That came after the new year, when on Feb. 22, 2021, the M2 annual rate of increase reached a staggering 27.5 percent.

At the very same time, the velocity of money behaved as one would expect in a crisis of this sort. It plummeted an incredible 23.4 percent in the second quarter. A crashing rate at which money is being spent puts deflationary pressure on prices regardless of what happens with money supply. In this case, the falling velocity was a temporary salvation. It pushed the bad effects of this quantitative easing—to invoke a euphemism from 2008—off into the future.

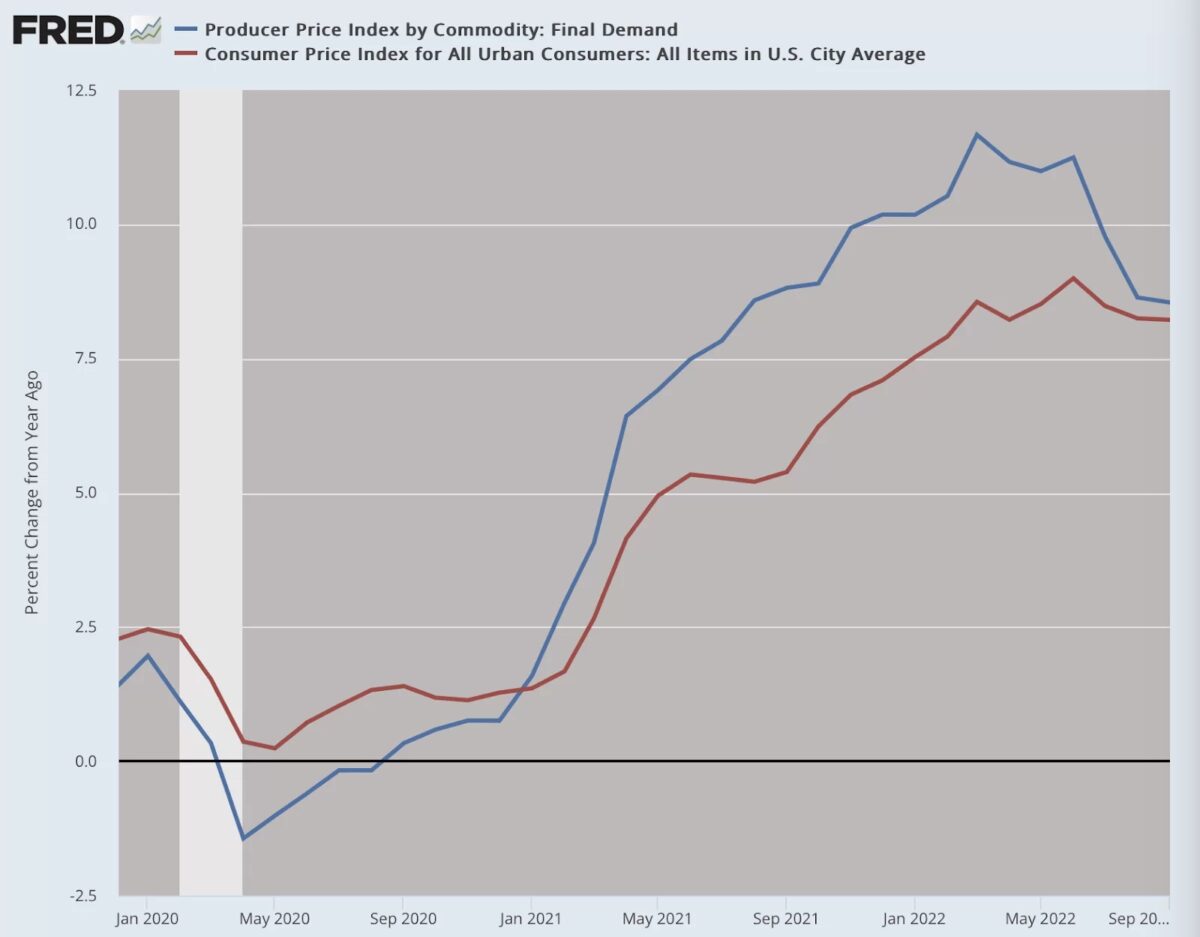

That future is now. The eventual result is the highest inflation in 40 years, which is not slowing down but accelerating, at least according to the Oct. 12, 2022 Producer Price Index, which is hotter than it has been in months. It is running ahead of the Consumer Price Index, which is a reversal from earlier in the lockdown period. This new pressure on producers heavily impacted the business environment and created recessionary conditions.

A Global Problem

Moreover, this was not just a U.S. problem. Most nations in the world followed the same lockdown strategy while attempting to substitute spending and printing for real economic activity. The cause-and-effect relationship holds the world over. Central banks coordinated and their societies all suffered.

The Fed is being called up daily to step up its lending to foreign central banks through the discount window for emergency loans. It is now at the highest level since Spring 2020 lockdowns. The Fed lent $6.5 billion to two foreign central banks in one week in October 2022. The numbers are truly scary and foreshadow a possible international financial crisis.

The Great Head Fake

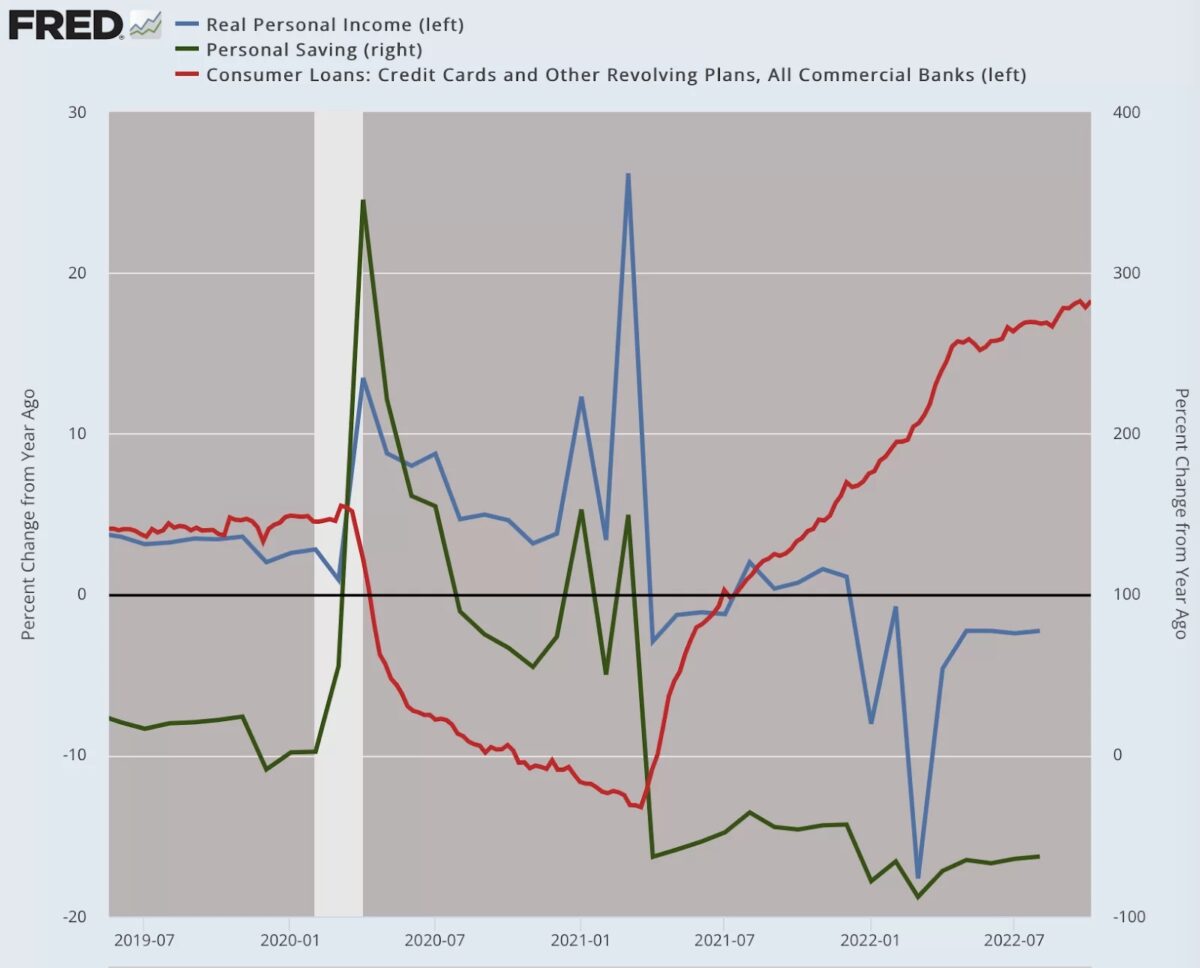

But back in the spring and summer of 2020, we seemed to experience a miracle. Governments around the country had crushed social functioning and free enterprise and yet real income went soaring. Between February 2020 and March 2021, real personal income during a time with low inflation was up by $4.2 trillion. It felt like magic: a lockdown economy but riches were pouring in.

And what did people do with their new-found riches? There was Amazon. There was Netflix. There was the need for all sorts of new equipment to feed our new existence as digital everything. All these companies benefited enormously while others suffered. Even so we paid off credit card debt. And much of the stimulus was socked away as savings. The first stimulus went straight to the bank: the personal savings rate went from 9.6 percent to 33 percent in the course of just one month.

After the summer, people started to get the hang of getting free money from government dropped into their bank accounts. The savings rate started to fall: by November 2020, it was back down to 13.3 percent. Once Joseph Biden came to power and unleashed another round of stimulus, the savings rate went back up to 26.3 percent. And just fast forward to the present and we find people saving 3.5 percent of income, which is half the historical norm dating back to 1960 and about where it was in 2005 when low interest rates fed the housing boom that went bust in 2008. Meanwhile credit card debt is now soaring, even though interest rates are 17 percent and higher.

In other words, we experienced the wildest swing from shocking riches to rags in a very short period of time. The curves all inverted once the inflation came along to eat out the value of the stimulus. All that free money turned out not to be free at all but rather very expensive. The dollar of January 2020 is now worth only $0.87, which is to say that the stimulus spending covered by Federal Reserve printing stole $0.13 of every dollar in the course of only 2.5 years.

It was one of the biggest head fakes in the history of modern economics. The pandemic planners created paper prosperity to cover up for the grim reality all around. But it did not and could not last.

Right on schedule, the value of the currency began to tumble. Between January 2021 and September 2022, prices increased 13.5 percent across the board, while costing the average American family $728 in September alone. Even if inflation stops today, the inflation already in the bag will cost the American family $8,739 over the next 12 months, leaving less money to pay off soaring credit card debt.

Let’s return to the salad days before the inflation hit and when the Zoom class experienced delight at their new riches and their work-from-home luxuries. On Main Street, matters looked very different. I visited two medium-sized towns in New Hampshire and Texas over the course of the summer of 2020. I found nearly all businesses on Main Street boarded up, malls empty but for a few masked maintenance men, and churches silent and abandoned. There was no life at all, only despair.

The look of most of America in those days—not even Florida was yet open—was post-apocalyptic, with vast numbers of people huddled at home either alone or with immediate families, fully convinced that a universally deadly virus was lurking outdoors and waiting to snatch the life of anyone foolish enough to seek exercise, sunshine, or, heaven forbid, fun with friends, much less visiting the elderly in nursing homes, which was verboten. Meanwhile, the CDC was recommending that any “essential business” install walls of plexiglass and paste social distancing stickers everywhere where people would walk. All in the name of science.

I am very aware that all of this sounds utterly ridiculous now, but I assure you that it was serious at the time. Several times, I was personally screamed at for walking only a few feet into a grocery aisle that had been designated by stickers to be one way in the other direction. Also in those days, at least in the Northeast, enforcers among the citizenry would fly drones around the city and countryside looking for house parties, weddings, or funerals, and snap images to send to the local media, which would dutifully report the supposed scandal.

These were times when people insisted on riding elevators alone, and only one person at a time was permitted to walk through narrow corridors. Parents masked up their kids even though the kids were at near zero risk, which we knew from data but not from public health authorities. Incredibly, nearly all schools were closed, thus forcing parents out of the office back home. Homeschooling, which has long existed under a legal fog, suddenly became mandatory.

Just to illustrate how crazy it all became, a friend of mine arrived home from a visit out of town and his mother demanded that he leave his COVID-infested bags on the porch for three days. I’m sure you have your own stories of absurdity, among which was the masking of everyone, the enforcement of which went from stern to ferocious as time passed.

But these were the days when people believed the virus was outdoors and so we should stay in. Oddly, this changed over time when people decided that the virus was indoors and so we should be outdoors. When New York City cautiously permitted dining in commercial establishments, the mayor’s office insisted that it could only be outdoors, so many restaurants built an outdoors version of indoors, complete with plastic walls and heating units at a very high expense.

In those days, I had some time to kill waiting for a train in Hudson, New York, and went to a wine bar. I ordered a glass at the counter and the masked clerk handed it to me and pointed for me to go outside. I said I would like to drink it inside since it was freezing and miserable outside. I pointed out that there was a full dining room right there. She said I could not because of COVID.

Is this a law, I asked? She said no it is just good practice to keep people safe.

“Do you really think there is COVID in that room?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said in all seriousness.

At this point, I realized we had fully moved from government-mandated mania to a real popular delusion for the ages.

The commercial carnage for small business has yet to be thoroughly documented. At least 100,000 restaurants and stores in Manhattan alone closed, commercial real estate prices crashed, and big business moved in to scoop up bargains. Policies were decidedly disadvantageous to small businesses. If there were commercial capacity restrictions, they would kill a coffee shop but a large franchise all-you-eat buffet that holds 300 would probably be fine.

So too with industries in general: big tech including Zoom and Amazon thrived, but hotels, bars, restaurants, malls, cruise ships, theaters, and anyone without home delivery suffered terribly. The arts were devastated. In the deadly Hong Kong flu of 1968–69, we had Woodstock but this time we had nothing but YouTube, unless you opposed COVID restrictions in which case your song was deleted and your account blasted into oblivion.

Health Care Industry

To talk about the healthcare industry, let’s return to the early days of the frenzy of the Spring of 2020. An edict had gone out from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to all public health officials in the country that strongly urged the closing of all hospitals to everyone but non-elective surgeries and COVID patients, which turned out to exclude nearly everyone who would routinely show up for diagnostics or other normal treatments.

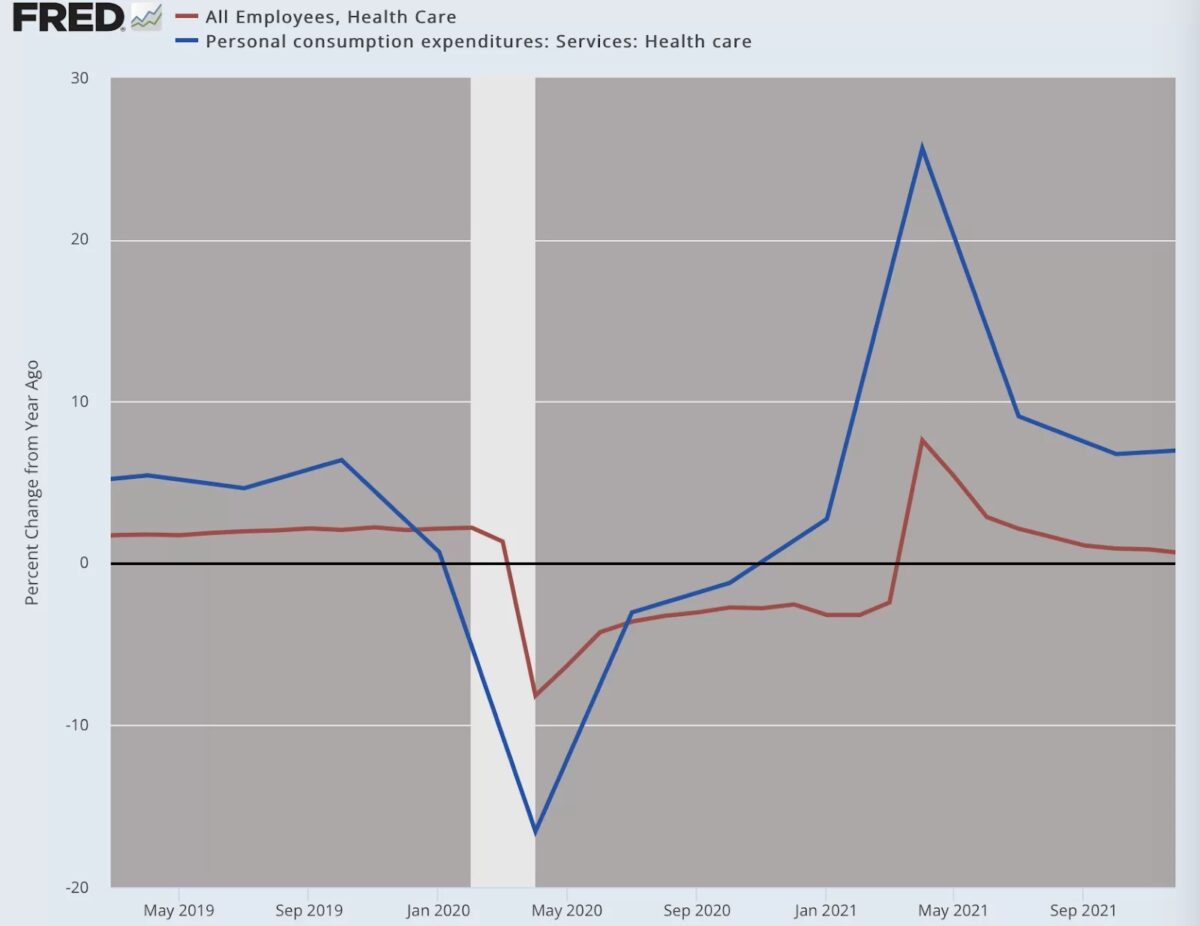

As a result, hospital parking lots emptied out from sea to shining sea, a most bizarre sight to see given that there was supposed to be a pandemic raging. We can see this in the data. The healthcare sector employed 16.4 million people in early 2020. By April, the entire sector lost 1.6 million employees, which is an astonishing exodus by any historical standard. Nurses in hundreds of hospitals were furloughed. Again, this happened during a pandemic.

In another strange twist that future historians will have a hard time trying to figure out, health care spending itself fell off a cliff. From March to May 2020, health care spending actually collapsed by $500 billion or 16.5 percent.

This created an enormous financial problem for hospitals in general, which, after all, are economic institutions too. They were bleeding money so fast that when the federal government offered subsidies of 20 percent above other respiratory ailments if the patient could be declared COVID positive, hospitals jumped at the chance and found cases galore, which the CDC was happy to accept at face value. Compliance with guidelines became the only path toward restoring profitability.

The throttling of non-COVID services included the near abolition of dentistry that went on for months from Spring through Summer. In the midst of this, I worried that I needed a root canal. I simply could not find a dentist in Massachusetts who would see me. They said every patient first needs a cleaning and thorough examination and all those have been canceled. I had the bright idea of traveling to Texas to get it done but the dentist there said they were restricted by law to make sure all patients from out of state quarantine in Texas for two weeks, time I could not afford. I thought about suggesting to my mother, who was making the appointment, that she simply lie about the date of my arrival but thought better of it given her scruples.

It was a time of great public insanity, not stopped and even fomented by public health bureaucrats. The abolition of dentistry for a time seemed to comply completely with the injunction of the New York Times on Feb. 28, 2020. “To Take on the Coronavirus, Go Medieval on It,” the headline read. We did, even to the point of abolishing dentistry, publicly shaming the diseased on grounds that getting COVID was surely a sign of noncompliance and civic sin, and instituting a feudal system of dividing workers by essential and nonessential.

Labor Markets

Exactly how it came to be that the entire workforce came to be divided this way remains a mystery to me but the guardians of the public mind seemed not to care a whit about it. Most of the delineated lists at the time said that you could keep operating if you qualified as a media center. Thus for two years did the New York Times instruct its readers to stay home and have their groceries delivered. By whom, they did not say, nor did they care because such people are not apparently among their reader base. Essentially, the working classes were used as fodder to obtain herd immunity, and then later subjected to vaccine mandates despite superior natural immunity.

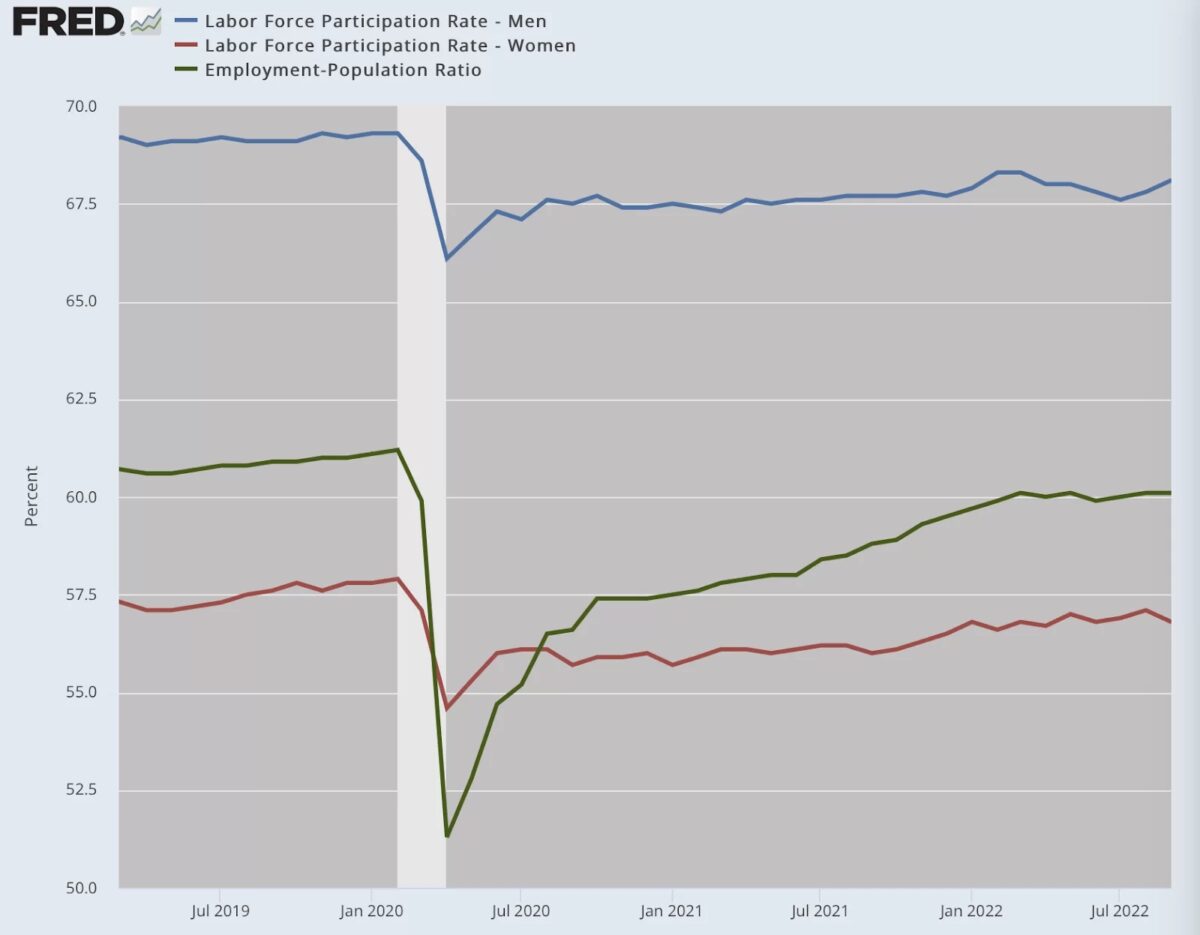

Many, as in millions, were later fired for not complying with mandates. We are told that unemployment today is very low and that many new jobs are being filled. Yes, and most of those are existing workers getting second and third jobs. Moonlighting and side gigging are now a way of life, not because it is a blast but because the bills have to be paid.

The full truth about labor markets requires that we look at the labor participation rate and the worker-population ratio. Millions have gone missing. These are working women who still cannot find child care because that industry never recovered, and so participation is back at 1988 levels. They are early retirements. They are 20 somethings who moved home and went on unemployment benefits. There are many more who have just lost the will to achieve and build a future.

The supply chain breakages need their own discussion. The March 12, 2020, evening announcement by President Trump that he would block all travel from Europe, UK, and Australia beginning in five days from then started a mad scramble to get back to the United States. He also misread the teleprompter and said that the ban would also apply to goods. The White House had to correct the statement the next day but the damage was already done. Shipping came to a complete standstill.

Supply Chains and Shortages

Most economic activity stopped. By the time the fall relaxation came and manufacturers started reordering parts, they found that many factories overseas had already retooled for other kinds of demand. This particularly affected the semiconductor industry for automotive manufacturing. Overseas chip makers had already turned their attention to personal computers, cellphones, and other devices. This was the beginning of the car shortage that sent prices through the roof. This created a political demand for U.S.-based chip production which has in turn resulted in another round of export and import controls.

These sorts of problems have affected every industry without exception. Why the paper shortage today? Because so many of the paper factories which shifted to plywood after that had gone sky-high in price to feed the housing demand created by generous stimulus checks.

We could write books listing all the economic calamities directly caused by the disastrous pandemic response. They will be with us for years, and yet even today, not many people fully grasp the relationship between our current economic hardships, and even the growing international tensions and breakdown of trade and travel, and the brutality of the pandemic response. It is all directly related.

Anthony Fauci said at the outset: “I don’t think about things like the economy and the secondary impacts.” And Melinda Gates said the same in a Dec. 4, 2020 interview with the New York Times: “What did surprise us is we hadn’t really thought through the economic impacts.”

The wall of separation posited between “economics” and public health did not hold in theory or practice. A healthy economy is indispensable for healthy people. Shutting down economic life was a singularly bad idea for taking on a pandemic.

Conclusion

Economics is about people in their choices and institutions that enable them to thrive. Public health is about the same thing. Driving a wedge between the two surely ranks among the most catastrophic public-policy decisions of our lifetimes. Health and economics both require the nonnegotiable called freedom. May we never again experiment with its near abolition in the name of disease mitigation.

This is based on a presentation at Hillsdale College, Oct. 20, 2022, to appear in a shortened version in Imprimis.

From the Brownstone Institute

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.