The Art of Japanese Archery

You may never have considered trying traditional Japanese archery—kyudo—but it offers a profound form of exercise that combines physical activity with mental clarity.In 1948, a slender paperback, “Zen in the Art of Archery,” by German philosophy professor Eugen Herrigel, introduced Westerners, particularly Americans, to Zen Buddhism. This is not a book on meditation; it is a book on Japanese archery. Herrigel had taught in Japan, where he became interested in Zen. He was advised to approach learning Zen through one of the Zen arts, such as calligraphy, archery, flower arranging, or the tea ceremony. Herrigel chose archery, and narrated his struggle to do it in the Zen way, letting go of his rationalist habits and learning to trust the intuitive and mystical Way of the Bow. Mindfulness is much sought after. But anyone who has tried meditation knows that it can be challenging to empty your mind; this is partly why Herrigel was advised to choose a physical art in which Zen practice is embodied. Traditional Japanese archery is highly formalized, and even the slightest movement has been prescribed and honed to the utmost gracefulness and efficiency. You cannot practice kyudo without attending closely to your body and breath. A Martial Art Close your eyes for a moment. Think of the sound an arrow makes as it is released from a bow. In your mind, you are probably hearing a “thwoosh,” a cross between a “whoosh” and a “thwang.” But that’s not the sound you will hear when you shoot an arrow in the Japanese style. Traditional Japanese archery uses very large bows made from bamboo. When you release an arrow—which your sensei won’t allow you to do until you’ve done dozens of hours of preparation—you hear a high-pitched whistle. When your arrow hits the target, it makes a clattering noise, like bamboo chimes blown together by the wind. My husband, 53, has been enthusiastic about archery since he got his first toy bow at the age of 7. Since high school, he has wanted to learn kyudo, but has never lived near one of the few places in the United States where it is practiced, until now. He recently found a kyudo center and a sensei to teach him. “I like how I feel like I’m engaging with archery in a deeper way,” he told me. “Kyudo is not about hitting the target. The objective is inside yourself.” Kyudo is done in a special building with one wall open to an outdoor target range. The archers stand perpendicular to the target with their legs splayed widely apart. They stand indoors and shoot out through the open wall toward the outdoor target. Every movement is formalized into a graceful ritual, from the first step into the room through the stance and the bow draw. Even where the archer looks and the timing of the breath are formalized. This is very different than Western archery; it is a moving meditation. The bamboo bow is about seven and a half feet long and asymmetrical. It is too long to hold in the middle, like in Western archery, so the kyudo archer must learn to hold it a third of the way up from the bottom. The bow makes the shape of a sail above the archer when it is drawn. The arrows are large, too—more than a meter long—and the string must be drawn further back than in the archery Westerners are used to, far behind the archer’s head. A Mind-Body Workout “Kyudo,” in Japanese, means the tao (way) of the bow. Japanese archery developed over millennia from its origins in hunting and warfare into the highly technical form the samurai perfected. As guns overtook archery’s importance in war in the 1500s, samurai preserved traditional archery by evolving it into a form of self-cultivation. The serene nature of this archery practice may not seem like exercise at first glance. But half an hour of it not only benefits your mind; it also gives you a full-body workout. Kyudo engages nearly every muscle in the upper body, as well as your calves, glutes, and core. Bows are drawn to one side. Since the motion is asymmetrical, you might assume that your muscles would develop unevenly. Yet both the left and right sides of the body are fully engaged, and your chest and stomach muscles are worked as well as your back muscles. There is an isometric component to archery—a static contraction of muscle without any visible movement in the joint. You have active pullback from the bow, and must hold it at full draw. Isometric exercise has been shown to be highly beneficial. According to Dr. Edward R. Laskowski, isometric exercise can help patients suffering from arthritis and may also help lower blood pressure. Interested in Archery? There are only a few dozen kyudo centers outside of Japan, but archery is a sport you can do almost anywhere. Some municipalities place limits on shooting a bow, but in many places, you can practice in your backyard. If you become interested in archery, you open up a wide range of other activities: You can try bowhunting, bow fishing, 3D shoots (a course through the woods with a series of life-si

You may never have considered trying traditional Japanese archery—kyudo—but it offers a profound form of exercise that combines physical activity with mental clarity.

In 1948, a slender paperback, “Zen in the Art of Archery,” by German philosophy professor Eugen Herrigel, introduced Westerners, particularly Americans, to Zen Buddhism. This is not a book on meditation; it is a book on Japanese archery.

Herrigel had taught in Japan, where he became interested in Zen. He was advised to approach learning Zen through one of the Zen arts, such as calligraphy, archery, flower arranging, or the tea ceremony. Herrigel chose archery, and narrated his struggle to do it in the Zen way, letting go of his rationalist habits and learning to trust the intuitive and mystical Way of the Bow.

Mindfulness is much sought after. But anyone who has tried meditation knows that it can be challenging to empty your mind; this is partly why Herrigel was advised to choose a physical art in which Zen practice is embodied. Traditional Japanese archery is highly formalized, and even the slightest movement has been prescribed and honed to the utmost gracefulness and efficiency. You cannot practice kyudo without attending closely to your body and breath.

A Martial Art

Close your eyes for a moment. Think of the sound an arrow makes as it is released from a bow. In your mind, you are probably hearing a “thwoosh,” a cross between a “whoosh” and a “thwang.” But that’s not the sound you will hear when you shoot an arrow in the Japanese style.

Traditional Japanese archery uses very large bows made from bamboo. When you release an arrow—which your sensei won’t allow you to do until you’ve done dozens of hours of preparation—you hear a high-pitched whistle. When your arrow hits the target, it makes a clattering noise, like bamboo chimes blown together by the wind.

My husband, 53, has been enthusiastic about archery since he got his first toy bow at the age of 7. Since high school, he has wanted to learn kyudo, but has never lived near one of the few places in the United States where it is practiced, until now. He recently found a kyudo center and a sensei to teach him.

“I like how I feel like I’m engaging with archery in a deeper way,” he told me. “Kyudo is not about hitting the target. The objective is inside yourself.”

Kyudo is done in a special building with one wall open to an outdoor target range. The archers stand perpendicular to the target with their legs splayed widely apart. They stand indoors and shoot out through the open wall toward the outdoor target. Every movement is formalized into a graceful ritual, from the first step into the room through the stance and the bow draw. Even where the archer looks and the timing of the breath are formalized. This is very different than Western archery; it is a moving meditation.

The bamboo bow is about seven and a half feet long and asymmetrical. It is too long to hold in the middle, like in Western archery, so the kyudo archer must learn to hold it a third of the way up from the bottom. The bow makes the shape of a sail above the archer when it is drawn. The arrows are large, too—more than a meter long—and the string must be drawn further back than in the archery Westerners are used to, far behind the archer’s head.

A Mind-Body Workout

“Kyudo,” in Japanese, means the tao (way) of the bow. Japanese archery developed over millennia from its origins in hunting and warfare into the highly technical form the samurai perfected. As guns overtook archery’s importance in war in the 1500s, samurai preserved traditional archery by evolving it into a form of self-cultivation.

The serene nature of this archery practice may not seem like exercise at first glance. But half an hour of it not only benefits your mind; it also gives you a full-body workout. Kyudo engages nearly every muscle in the upper body, as well as your calves, glutes, and core.

Bows are drawn to one side. Since the motion is asymmetrical, you might assume that your muscles would develop unevenly. Yet both the left and right sides of the body are fully engaged, and your chest and stomach muscles are worked as well as your back muscles.

There is an isometric component to archery—a static contraction of muscle without any visible movement in the joint. You have active pullback from the bow, and must hold it at full draw. Isometric exercise has been shown to be highly beneficial. According to Dr. Edward R. Laskowski, isometric exercise can help patients suffering from arthritis and may also help lower blood pressure.

Interested in Archery?

There are only a few dozen kyudo centers outside of Japan, but archery is a sport you can do almost anywhere.

Some municipalities place limits on shooting a bow, but in many places, you can practice in your backyard. If you become interested in archery, you open up a wide range of other activities: You can try bowhunting, bow fishing, 3D shoots (a course through the woods with a series of life-size foam animals to shoot at, with a scorecard like golf), or even archery tag or a dodgeball-like game using foam-tipped arrows.

You don’t need a giant kyudo bow or an expensive mechanical compound bow, like hunters use, to enjoy archery. Before you buy your own bow, consider taking an archery class at a local range or recreation center that can provide the required equipment.

If you take to the sport, the equipment you need (a bow, arrows, archery glove, quiver, target, and backstop) can be purchased at an archery store, where you can try out different brands and models. Basic equipment can be quite inexpensive and can also be found used for even less.

If you want to practice at home, but don’t have a backyard space or an appropriate backstop, just use foam-tipped arrows, widely available for live-action role playing. For safety reasons, foam-tipped arrows are a good choice for beginners and young children.

If you would like to study kyudo, you can find a sensei by contacting American Kyudo Renmei, a nonprofit organization with a mission to promote Japanese archery in the Americas. The states where kyudo is being practiced include California, Georgia, Indiana, Minnesota, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington.

Different Forms of Archery

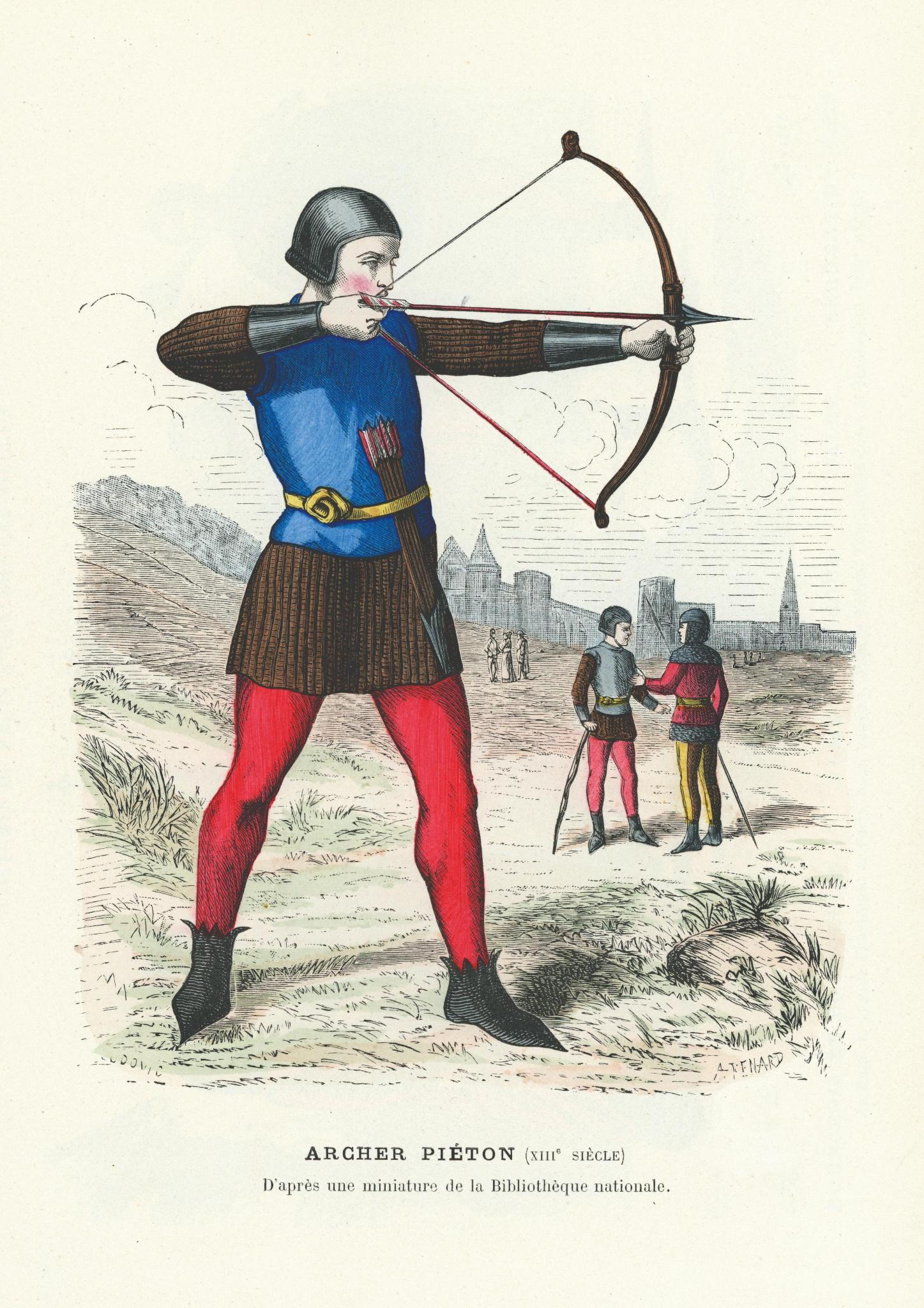

Western archery: “Mediterranean archery”—the type of archery most people in the West are familiar with—is what children in the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts learn, and this archery style has been part of the modern Olympic games since 1900. Important during the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), it was practiced with English longbows. After the Middle Ages, this form of archery was barely practiced for 400 years, and came back into favor in the 19th century as a leisure pastime. In Western archery, you stand perpendicular to the target, use three fingers to pull the bow, and only draw the string back, with your right hand, to just in front of your face.

Korean archery: Korean archery is at the root of Korean cultural identity and is still much revered today, as the practice of archery was how the Koreans preserved their independence for centuries. In Korean archery, you use a very short, very curvy bow that is pulled with a special thumb ring, and you shoot at targets 140 meters (about 150 yards) away—about twice the distance of targets in the Olympics.

Chinese traditional archery: Although the art of traditional Chinese bowmaking was nearly lost during the Cultural Revolution, Chinese traditional archery is making a comeback both in China and abroad. This form of archery uses a three-layered, curvy medium-length bow, made of wood, water buffalo horn, and sinew. Archers use the “inchworm technique,” in which the elbow of the drawing arm is pulled up overhead like an inchworm. China has embraced many forms of archery in its long history, and its importance is reflected in the fact that today, there are more than 100 million people named Zhang—“Archer” in Chinese.

Tatar and Mongolian archery: The Tatars and Mongols excelled in horseback archery, shooting at their foes while galloping on the short ponies of the Asian Steppes. They used very short and curvy three-layered bows. Horseback archery, Genghis Khan’s weapon of conquest in large swaths of Asia, allowed his men to be fast and mobile as they fought their enemies.

Jennifer Margulis, Ph.D., is an award-winning journalist and a frequent contributor to the Epoch Times. Learn more and sign up for her weekly emails at JenniferMargulis.net.

This article was originally published in Radiant Life magazine.