Remembering Pope Benedict XVI: A Man of Truth, Faith, and Tradition

CommentaryBefore he became Pope, a Mexican colleague of mine and her family saw Cardinal Ratzinger near the Vatican. They introduced themselves, and he graciously took the time to get to know them. He then asked them a series of questions about the Church in Mexico. My colleague remarked on the depth of his questions and his eagerness to learn from people “on the ground.” Then he showed his characteristic humility when the family asked for a photo. He took the camera and suggested the best angle from which he could take their picture. When they said they wanted him in the photo, he could not understand why they thought he was that important. In an age afflicted by the cult of personality, Benedict was a genuinely humble man and the opposite of so many of today’s “celebrities.” Benedict knew that wisdom came from asking the right questions and from pivotal insights through which people could come to their own knowledge of the truth. That was very clear when he spoke to a contentious synod of bishops that was going nowhere. He listened carefully, then spoke for a few minutes, not as an authoritarian, but as an intellectual leader who highlighted what was most important about the Church’s tradition. He then left, and as one observer said, it was as if a weight had been lifted, and the gathered bishops could come to a positive agreement. Having witnessed Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Benedict knew the power of truth and its abuse by authoritarian regimes. Whether it was misinforming people about the nature of humanity or by suppressing coverage of events like Tiananmen Square, he knew that through various methods, these regimes would repress objective truth in favour of the twisted version that would serve their purposes. Photographer Jeff Widener’s iconic Tank Man shot, in Tiananmen Square, China, on June 5, 1989. (Jeff Weidner) But while many contemporary people offered relativism as an alternative, Benedict knew that relativism was both logically wrong and dangerous to our society. Our society’s greatest needs were “truth and love.” Truth liberates us from the “dictatorship of relativism” that would see society tossed about by the latest trends of the day. Love drives humanity to its highest purpose and deepest fulfilment. Together truth and love make people accountable not to this or that regime or social trend but to the highest and most transcendent of values. Benedict’s own values, his commitment to truth and honesty, were shown clearly in his dealing with Father Maciel. Before Benedict became Pope, Maciel got away with the most despicable of crimes. He lavished expensive upon Church leaders so that few if any, dared to touch him. As Cardinal Ratzinger, he was one of the very few Church leaders to refuse these gifts. When he became Pope, Benedict reopened the investigation into Maciel and removed him from active ministry. What Is a Society Without Faith? Benedict was also a prominent advocate of faith, tradition, and culture. He knew that a just society would be impossible without religious faith, a conviction boosted by his experience of authoritarian regimes that suppressed traditional faith. He also argued that eliminating faith from modern society did not have the liberating effect that some would have hoped. He challenged us to ask if eliminating faith from daily life really made people happier or really made people free? He asked if a society without faith in the transcendent could achieve freedom, peace and justice? On the contrary, he argued that it was religious faith that, “gave rise to the idea of human rights, the idea of the equality of all people before the law, the recognition of the inviolability of human dignity in every single person and the awareness of people’s responsibility for their actions.” Perhaps this is why faith is so ruthlessly attacked by regimes that routinely violate the human rights of their citizens. Pope Benedict XVI gives Christmas Night Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, Vatican, on Dec. 24, 2009. (Franco Origlia/Getty Images) Benedict also knew the value of tradition. He started his theological career as a liberal. He believed in scholarship and a Church that was thoroughly up-to-date. But he also came to appreciate that we should proceed with caution and fidelity to our tradition and values. To see ourselves not as destroying all that is old in order to create the new, but to be people who are bearers of a tradition—carrying forth what our culture has given us from the past in order to create a wiser, better-grounded future. While his impact will be felt mostly by Catholics, Pope Benedict remains an inspiration for people of all faiths. The values for which he stood are universal, and the way to genuine peace and prosperity. They are also the things feared most by authoritarian regimes. From Nazi Germany to the Chinese Communist Party, their leaders have known that they will never be brought down by bombs and bullets but

Commentary

Before he became Pope, a Mexican colleague of mine and her family saw Cardinal Ratzinger near the Vatican. They introduced themselves, and he graciously took the time to get to know them. He then asked them a series of questions about the Church in Mexico.

My colleague remarked on the depth of his questions and his eagerness to learn from people “on the ground.”

Then he showed his characteristic humility when the family asked for a photo. He took the camera and suggested the best angle from which he could take their picture. When they said they wanted him in the photo, he could not understand why they thought he was that important.

In an age afflicted by the cult of personality, Benedict was a genuinely humble man and the opposite of so many of today’s “celebrities.”

Benedict knew that wisdom came from asking the right questions and from pivotal insights through which people could come to their own knowledge of the truth.

That was very clear when he spoke to a contentious synod of bishops that was going nowhere. He listened carefully, then spoke for a few minutes, not as an authoritarian, but as an intellectual leader who highlighted what was most important about the Church’s tradition. He then left, and as one observer said, it was as if a weight had been lifted, and the gathered bishops could come to a positive agreement.

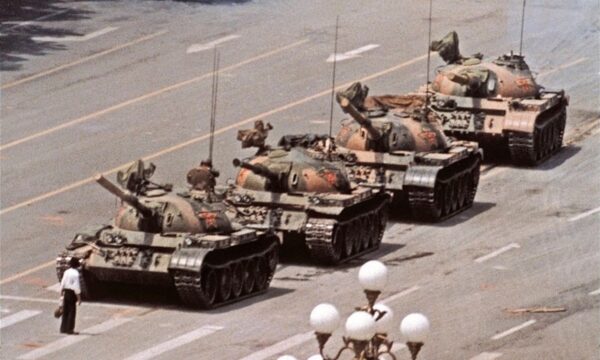

Having witnessed Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Benedict knew the power of truth and its abuse by authoritarian regimes. Whether it was misinforming people about the nature of humanity or by suppressing coverage of events like Tiananmen Square, he knew that through various methods, these regimes would repress objective truth in favour of the twisted version that would serve their purposes.

But while many contemporary people offered relativism as an alternative, Benedict knew that relativism was both logically wrong and dangerous to our society.

Our society’s greatest needs were “truth and love.”

Truth liberates us from the “dictatorship of relativism” that would see society tossed about by the latest trends of the day. Love drives humanity to its highest purpose and deepest fulfilment.

Together truth and love make people accountable not to this or that regime or social trend but to the highest and most transcendent of values.

Benedict’s own values, his commitment to truth and honesty, were shown clearly in his dealing with Father Maciel.

Before Benedict became Pope, Maciel got away with the most despicable of crimes. He lavished expensive upon Church leaders so that few if any, dared to touch him.

As Cardinal Ratzinger, he was one of the very few Church leaders to refuse these gifts. When he became Pope, Benedict reopened the investigation into Maciel and removed him from active ministry.

What Is a Society Without Faith?

Benedict was also a prominent advocate of faith, tradition, and culture. He knew that a just society would be impossible without religious faith, a conviction boosted by his experience of authoritarian regimes that suppressed traditional faith.

He also argued that eliminating faith from modern society did not have the liberating effect that some would have hoped. He challenged us to ask if eliminating faith from daily life really made people happier or really made people free?

He asked if a society without faith in the transcendent could achieve freedom, peace and justice?

On the contrary, he argued that it was religious faith that, “gave rise to the idea of human rights, the idea of the equality of all people before the law, the recognition of the inviolability of human dignity in every single person and the awareness of people’s responsibility for their actions.”

Perhaps this is why faith is so ruthlessly attacked by regimes that routinely violate the human rights of their citizens.

Benedict also knew the value of tradition. He started his theological career as a liberal. He believed in scholarship and a Church that was thoroughly up-to-date.

But he also came to appreciate that we should proceed with caution and fidelity to our tradition and values. To see ourselves not as destroying all that is old in order to create the new, but to be people who are bearers of a tradition—carrying forth what our culture has given us from the past in order to create a wiser, better-grounded future.

While his impact will be felt mostly by Catholics, Pope Benedict remains an inspiration for people of all faiths.

The values for which he stood are universal, and the way to genuine peace and prosperity. They are also the things feared most by authoritarian regimes.

From Nazi Germany to the Chinese Communist Party, their leaders have known that they will never be brought down by bombs and bullets but by the enduring power of the truth, faith and tradition proclaimed by great men like Pope Benedict.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.