No One Wants to Drive Down This Memory Lane

Commentary One month ago, all anyone would—or could—talk about were gas prices. What the country was paying for fuel was outrageous, it seemed. Despite oil prices settling a touch after the big spike in March, this wasn’t the case for Americans paying only more at the pump. By the middle of June, the price per gallon of average regular gasoline was $5.016, according to AAA. Since then, the average regular gallon has become about $0.55 cheaper, and everyone wants to take credit. President Joe Biden recently went to Saudi Arabia begging the Saudis and their oil-producing cronies for more. However, he came home empty-handed: no new supply commitments from the OPEC+3 countries. Still, on Twitter and across other social media platforms, the White House hasn’t been shy to point out this substantial decline in average fuel. Just a few days ago, when asked about it, the president said, “There’s been a real change”—before adding, “They’ve [gas prices] been coming down every single day, to the best of my knowledge.” But Why? Clearly, those at the top in government want to insinuate themselves and their policies into this less-awful part of the conversation. An undecided public is then led to make that specific connection, to view official statements as if they correlated with falling gas prices (though, as typical, most every discussion of cause and effect will immediately break down along partisan lines). Neither party is likely to offer the correct explanation. In this case, it is distinctly a macro issue, not a political one. The government’s own data are rather unambiguous on this score. While it isn’t yet conclusive, the trends have run long enough to be more than compelling, and not all that far from becoming definite. According to the Department of Energy’s U.S. Energy Information Administration (U.S. EIA), weekly gasoline supplied to the domestic economy for use by consumers and businesses alike was just 8.52 million barrels per day (mbpd) last week (July 15). The week prior (July 8), demand was 8.06 mbpd. These are astoundingly low estimates (see chart above), particularly for this time of year. Americans are famous for their summer driving habits—and why not? Apart from South Florida, where I currently reside, most of the country is absolutely beautiful and pleasant during July into August. Vacations as well as midyear ramping up of business, it is normal to see the steady demand for motor fuel. Not This Year—Not Even Close Just how bad is 8.06 to 8.52 mpbd? Those weekly totals, covering the first half of the gorgeous month of July, were less than the same two weeks … in 2020. Let me repeat that: using reliable government data, the entire U.S. economy used less gasoline recently than it had back when most of it was closed off and deep down in the dumps. Remember July 2020? Following the initial reopening relief in May, we all settled pretty quickly into realizing just how overboard pandemic panic had gone, and what harm it had already meant to the economy, just as it affected daily life. Restrictions were still everywhere; jobs were only trickling back. Nobody went on vacation, so there was hardly much business (at the margins) use for gasoline or diesel. Going back to the U.S. EIA’s same estimates for gasoline product supplied, the United States still managed to use up 8.77 mpbd during the first week of July 2020 and 8.65 mpbd the following month. Not only have we all demanded less gasoline so far in July 2022, it has actually been a lot less gasoline. Alarmingly less. You can actually see this recession trend building all the way since March. At that time, the economy was somewhat on track, at least consistent with the seasonal history of gasoline demanded over the past decade. Once March’s oil surge registered, and it passed into distillate fuels, that is when use first began to fall off (and the wider implications of the falling off were increasingly priced into markets and curves). By the time gasoline reached its painful zenith a month ago, American use of the stuff initially dropped below its 2020 comparison. Following a short-lived rebound to finish up June, here we are in the first half of July economically soured on a lifeblood commodity. With so much of it since being left at the pump, domestic inventories have conspicuously changed (see chart above). Even though general crude oil production has remained low, and refining runs constrained—meaning that overall supplies continue to be exceedingly tight—gasoline stocks are rapidly building very much contrary to typical seasonal trends (i.e., summertime drawdowns). The increasingly dour and dire and broader implications for the whole economy is why gasoline prices have come down—not because of political interference. Should these highly unfavorable trends continue, gasoline will continue to fall over the weeks and months ahead—which is obviously not the good news the president and his administration is trying to claim. Other p

Commentary

One month ago, all anyone would—or could—talk about were gas prices. What the country was paying for fuel was outrageous, it seemed. Despite oil prices settling a touch after the big spike in March, this wasn’t the case for Americans paying only more at the pump.

By the middle of June, the price per gallon of average regular gasoline was $5.016, according to AAA.

Since then, the average regular gallon has become about $0.55 cheaper, and everyone wants to take credit.

President Joe Biden recently went to Saudi Arabia begging the Saudis and their oil-producing cronies for more. However, he came home empty-handed: no new supply commitments from the OPEC+3 countries.

Still, on Twitter and across other social media platforms, the White House hasn’t been shy to point out this substantial decline in average fuel. Just a few days ago, when asked about it, the president said, “There’s been a real change”—before adding, “They’ve [gas prices] been coming down every single day, to the best of my knowledge.”

But Why?

Clearly, those at the top in government want to insinuate themselves and their policies into this less-awful part of the conversation. An undecided public is then led to make that specific connection, to view official statements as if they correlated with falling gas prices (though, as typical, most every discussion of cause and effect will immediately break down along partisan lines).

Neither party is likely to offer the correct explanation. In this case, it is distinctly a macro issue, not a political one.

The government’s own data are rather unambiguous on this score. While it isn’t yet conclusive, the trends have run long enough to be more than compelling, and not all that far from becoming definite.

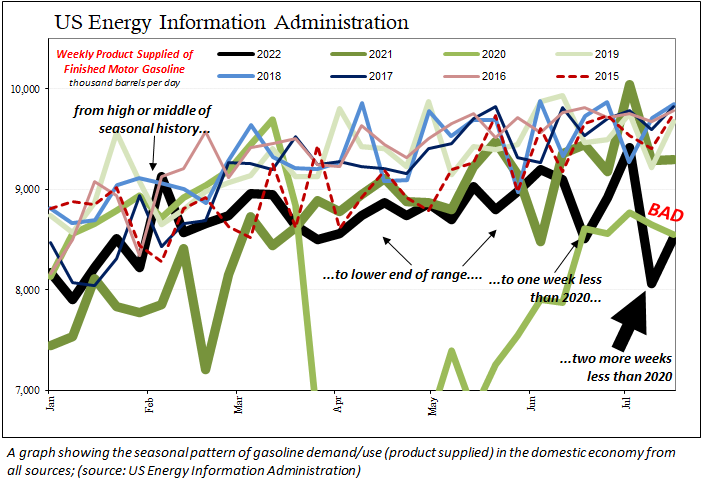

According to the Department of Energy’s U.S. Energy Information Administration (U.S. EIA), weekly gasoline supplied to the domestic economy for use by consumers and businesses alike was just 8.52 million barrels per day (mbpd) last week (July 15). The week prior (July 8), demand was 8.06 mbpd.

These are astoundingly low estimates (see chart above), particularly for this time of year. Americans are famous for their summer driving habits—and why not? Apart from South Florida, where I currently reside, most of the country is absolutely beautiful and pleasant during July into August. Vacations as well as midyear ramping up of business, it is normal to see the steady demand for motor fuel.

Not This Year—Not Even Close

Just how bad is 8.06 to 8.52 mpbd? Those weekly totals, covering the first half of the gorgeous month of July, were less than the same two weeks … in 2020. Let me repeat that: using reliable government data, the entire U.S. economy used less gasoline recently than it had back when most of it was closed off and deep down in the dumps.

Remember July 2020? Following the initial reopening relief in May, we all settled pretty quickly into realizing just how overboard pandemic panic had gone, and what harm it had already meant to the economy, just as it affected daily life. Restrictions were still everywhere; jobs were only trickling back.

Nobody went on vacation, so there was hardly much business (at the margins) use for gasoline or diesel. Going back to the U.S. EIA’s same estimates for gasoline product supplied, the United States still managed to use up 8.77 mpbd during the first week of July 2020 and 8.65 mpbd the following month.

Not only have we all demanded less gasoline so far in July 2022, it has actually been a lot less gasoline. Alarmingly less.

You can actually see this recession trend building all the way since March. At that time, the economy was somewhat on track, at least consistent with the seasonal history of gasoline demanded over the past decade. Once March’s oil surge registered, and it passed into distillate fuels, that is when use first began to fall off (and the wider implications of the falling off were increasingly priced into markets and curves).

By the time gasoline reached its painful zenith a month ago, American use of the stuff initially dropped below its 2020 comparison. Following a short-lived rebound to finish up June, here we are in the first half of July economically soured on a lifeblood commodity.

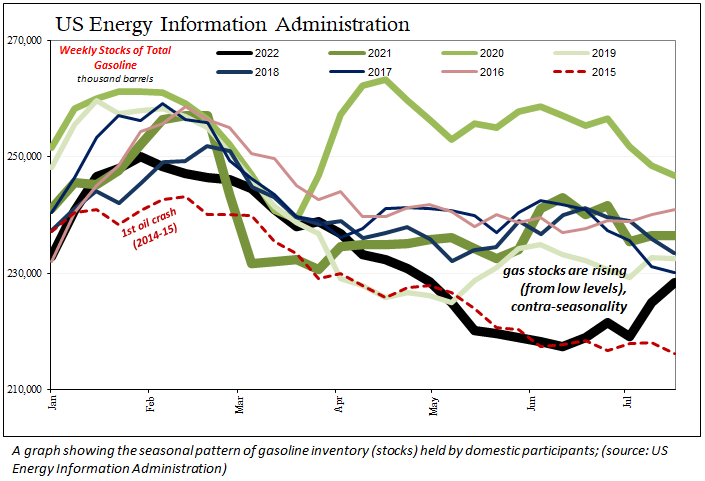

With so much of it since being left at the pump, domestic inventories have conspicuously changed (see chart above). Even though general crude oil production has remained low, and refining runs constrained—meaning that overall supplies continue to be exceedingly tight—gasoline stocks are rapidly building very much contrary to typical seasonal trends (i.e., summertime drawdowns).

The increasingly dour and dire and broader implications for the whole economy is why gasoline prices have come down—not because of political interference. Should these highly unfavorable trends continue, gasoline will continue to fall over the weeks and months ahead—which is obviously not the good news the president and his administration is trying to claim.

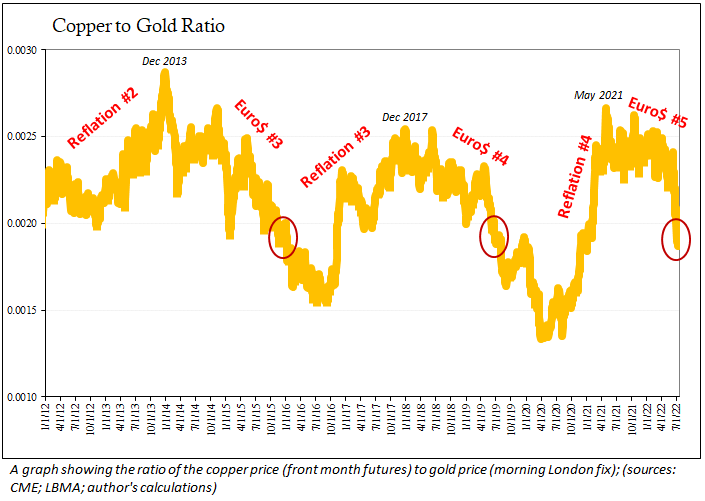

Other parts of key commodity markets have been pricing-in this scenario for months. Copper is a key industrial ingredient, while gold a safe haven. The former is susceptible to broad shifts in global economic circumstances, while the latter is sensitive to turmoil.

As a result, the copper-to-gold ratio has shifted decidedly in the recession direction, just as gross demand destruction has been clearly plotted out by the federal government’s energy estimates. Both metal prices have fallen, gold significantly less than copper; the market is tilting categorically toward safe haven.

Each and every time the global economy has surrendered to a macroeconomic downturn and recession in recent years the copper-to-gold ratio has captured the downturn. This is a dependable, slightly forward-looking indicator that isn’t dependent upon the politics of government or those practiced in 2022 by the wrongfooted fools at the Federal Reserve still claiming that rate hikes are needed and could somehow be effective at “controlling” inflation.

In this latest twist of irony, gasoline prices have apparently done that job already.

Both yield-curve distortion and eurodollar futures extremes—the latter inverted to a degree not seen since September 2007—had priced in, in real time, the results we are just now seeing emerge in our actual economic circumstances. It isn’t merely that American consumers and U.S. businesses are driving less: these economic fallouts are what happens across the overall economy because they drive less, and why.

Wearily, we need only remember back to the summer of 2020 for comparison.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.