New South Wales Digs Itself Into Coal Reserve Hole

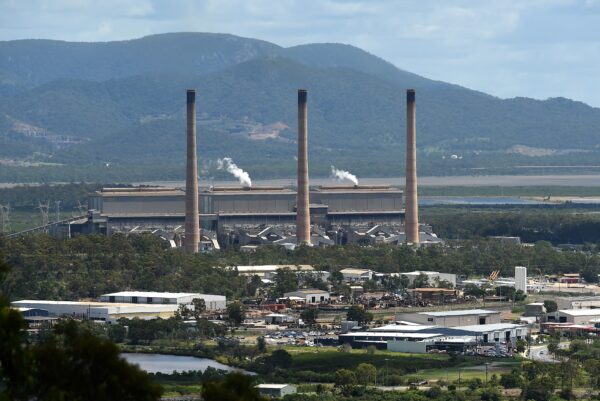

Commentary New South Wales (NSW) has introduced a reservation policy for coal. A certain portion of coal produced in the state will be required by law to be sold within the state. The policy will likely come into effect on the 1st of April, but that doesn’t mean it’s a joke. This is one more infuriating move from a supposedly centre-right state government that doesn’t even pretend to understand the economic principles that should define it. Yet it has been said that choice in government is a fiction of politics. In the case of the NSW government, this policy is not a pivot point. It has been expected—in fact, economically inevitable—since the federal government announced price caps on the industry late last year. Coal and gas are both commodities that Australia produces in vast quantities and sells on the international market. As a result, the domestic purchaser has to outbid international buyers if they are buying from the short-term market. This happened last year. The international price of all energy commodities increased, firstly due to post-COVID rebound, and secondly due to an energy-hungry Europe that was deprived of Russian gas in the lead-up to winter. A train transports coal through the valleys of Singleton in New South Wales, Australia, on Nov. 4, 2021. (Saeed Khan/AFP via Getty Images) When the international price soared, domestic prices followed. The federal government reacted to the high prices by announcing a wholesale price cap for gas and coal. This means that when coal producers sell to the domestic market, they are not permitted to sell above $125 per tonne (US$85). Quotas on Coal Exports Were Inevitable Price caps can do one of two things. The first is the cap has no effect because the natural market price is below the cap. Secondly, if the market price goes above the price cap, it can result in insufficient supply to meet the soaring demand. Shortages or nothing … these are the only two effects of price caps, which make them the very worst sort of policy, especially when they are introduced as a reaction to high prices caused by … yep, shortages. The counter-argument with coal and gas is that only the domestic price is capped and there is abundant supply to feed a domestic market that is relatively small compared to the exported volumes. However, the moment the cap comes into effect, any producer capable of exporting will seek to do so. The uncapped international price instantly “out-bids” the capped domestic price. Hence, the potential to export actually amplifies the magnitude of the shortages that would occur. So even when there is abundant supply to feed a hungry international market, a price cap policy on its own can only ever exacerbate a supply problem. It must be balanced by another policy, a policy that forces producers to sell domestically what they could otherwise sell internationally: reservation. This policy was economically inescapable. From Hard to Worse … The farcical element of the policy, however, is that the government now has to decide which producers are obliged to reserve which quantities. Different mines produce different grades of coal, which corresponding power stations have been designed to consume. Different grades also fetch different prices, so some take a large hit from the price caps whereas others are less affected. Some high-grade coal mines will no longer return any profit at all. The various mines also enjoy physical proximity to different infrastructures—so some producers can only sell domestically, some can only export, whereas others are flexible. A general view of the coal-powered Gladstone Power Station in Queensland, Australia, on March 23, 2016. (AAP Image/Dan Peled) Through the working of natural market forces along with careful planning of the business case of each mine, the industry can resolve all of these issues continuously. Now the government has come lumbering in, hitting them with reservation percentages like it’s a game of whack-a-mole. They can’t even design the policy well: understanding the intricacies of a market is not something to be done in one evening. Imagine if the economy was allowed to function correctly. First, due to high demand, prices go high, and coal exporters begin enjoying “windfall profits.” Then, during this period of high profits, those who have invested in coal production are able to make money, recover their investment, and receive cash to reinvest in more coal production which would … increase supply and help solve the supply problem, driving prices back downward. Imagine if the government, concerned about high prices, did not interfere with this process, but rather accelerated it. Even providing support to the poorest people, to help them pay their energy bills, would have a better effect than artificially lowering the prices. Instead, the government has entered a wrestling match with the economy itself. The giant invisible hand of the economy is seeking to allocate global res

Commentary

New South Wales (NSW) has introduced a reservation policy for coal. A certain portion of coal produced in the state will be required by law to be sold within the state.

The policy will likely come into effect on the 1st of April, but that doesn’t mean it’s a joke.

This is one more infuriating move from a supposedly centre-right state government that doesn’t even pretend to understand the economic principles that should define it.

Yet it has been said that choice in government is a fiction of politics.

In the case of the NSW government, this policy is not a pivot point. It has been expected—in fact, economically inevitable—since the federal government announced price caps on the industry late last year.

Coal and gas are both commodities that Australia produces in vast quantities and sells on the international market. As a result, the domestic purchaser has to outbid international buyers if they are buying from the short-term market.

This happened last year. The international price of all energy commodities increased, firstly due to post-COVID rebound, and secondly due to an energy-hungry Europe that was deprived of Russian gas in the lead-up to winter.

When the international price soared, domestic prices followed.

The federal government reacted to the high prices by announcing a wholesale price cap for gas and coal. This means that when coal producers sell to the domestic market, they are not permitted to sell above $125 per tonne (US$85).

Quotas on Coal Exports Were Inevitable

Price caps can do one of two things.

The first is the cap has no effect because the natural market price is below the cap. Secondly, if the market price goes above the price cap, it can result in insufficient supply to meet the soaring demand.

Shortages or nothing … these are the only two effects of price caps, which make them the very worst sort of policy, especially when they are introduced as a reaction to high prices caused by … yep, shortages.

The counter-argument with coal and gas is that only the domestic price is capped and there is abundant supply to feed a domestic market that is relatively small compared to the exported volumes.

However, the moment the cap comes into effect, any producer capable of exporting will seek to do so. The uncapped international price instantly “out-bids” the capped domestic price. Hence, the potential to export actually amplifies the magnitude of the shortages that would occur.

So even when there is abundant supply to feed a hungry international market, a price cap policy on its own can only ever exacerbate a supply problem. It must be balanced by another policy, a policy that forces producers to sell domestically what they could otherwise sell internationally: reservation.

This policy was economically inescapable.

From Hard to Worse …

The farcical element of the policy, however, is that the government now has to decide which producers are obliged to reserve which quantities. Different mines produce different grades of coal, which corresponding power stations have been designed to consume.

Different grades also fetch different prices, so some take a large hit from the price caps whereas others are less affected. Some high-grade coal mines will no longer return any profit at all.

The various mines also enjoy physical proximity to different infrastructures—so some producers can only sell domestically, some can only export, whereas others are flexible.

Through the working of natural market forces along with careful planning of the business case of each mine, the industry can resolve all of these issues continuously.

Now the government has come lumbering in, hitting them with reservation percentages like it’s a game of whack-a-mole.

They can’t even design the policy well: understanding the intricacies of a market is not something to be done in one evening.

Imagine if the economy was allowed to function correctly. First, due to high demand, prices go high, and coal exporters begin enjoying “windfall profits.”

Then, during this period of high profits, those who have invested in coal production are able to make money, recover their investment, and receive cash to reinvest in more coal production which would … increase supply and help solve the supply problem, driving prices back downward.

Imagine if the government, concerned about high prices, did not interfere with this process, but rather accelerated it. Even providing support to the poorest people, to help them pay their energy bills, would have a better effect than artificially lowering the prices.

Instead, the government has entered a wrestling match with the economy itself. The giant invisible hand of the economy is seeking to allocate global resources to the energy sector, particularly the reliable, established sources of energy, fossil fuels.

Governments worldwide are seeking to strangle that, by introducing windfall taxes, capping revenue, blocking projects, and using up the needed resources on their preferred alternatives—renewables, batteries, state interconnectors, electric vehicles, and the like.

It’s a disastrous recipe. The government’s own astronomical debt shows how good they truly are at allocating resources.

In reality, extensive government intervention will mainly serve to slow economic recovery. This has happened before—after the GFC in 2008, President Barack Obama presided over the slowest recovery since World War II. Now President Joe Biden has turned what was looking like a V-shaped recovery into a recession.

Despite What Critics Say, All Is Not Rosy in the World of Coal

Revenue has certainly been high for the mining sector in general, and this is responsible for Australia’s record-breaking trade surplus over the last 12 months. But all is not rosy.

Though mining companies are seeing high revenue, they are also seeing high costs. Labour, fuel, and anything bought through international supply chains are all expensive at the moment, or simply not available, due to shortages in each of these areas.

Australia has had reduced export volumes despite high prices. Weather has interfered with shiploading, some mines became waterlogged, a train crash in Queensland disrupted supply to their Gladstone port.

The Australian coal industry is struggling to resource the activity needed to boost production, and instead still sees a slump in export volumes compared to pre-pandemic levels.

It is frustrating to see a Liberal (centre-right) government being in lock-step with the national Labor (centre-left) government’s disastrous energy policies.

They support electricity policies focusing obsessively on fantastical long-term objectives, the “energy transition,” but neglect the very basic short-term problems that nearly derailed the east coast electricity network only last May.

They support the control of prices on fossil fuels, exacerbating existing supply shortfalls. They repeatedly demonise the fossil fuel industry for its “super profits” during this “illegal war in Ukraine.”

On one hand, they pat themselves on the back for greenlighting the Narrabri gas project (without government intervention, the project would have proceeded 10 years ago). On the other, they promise to prevent off-shore exploration for gas. All of this also discourages investment.

The NSW government may not have many options on this particular decision, but that is only because of all the missed exits in their rear-view mirror.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.