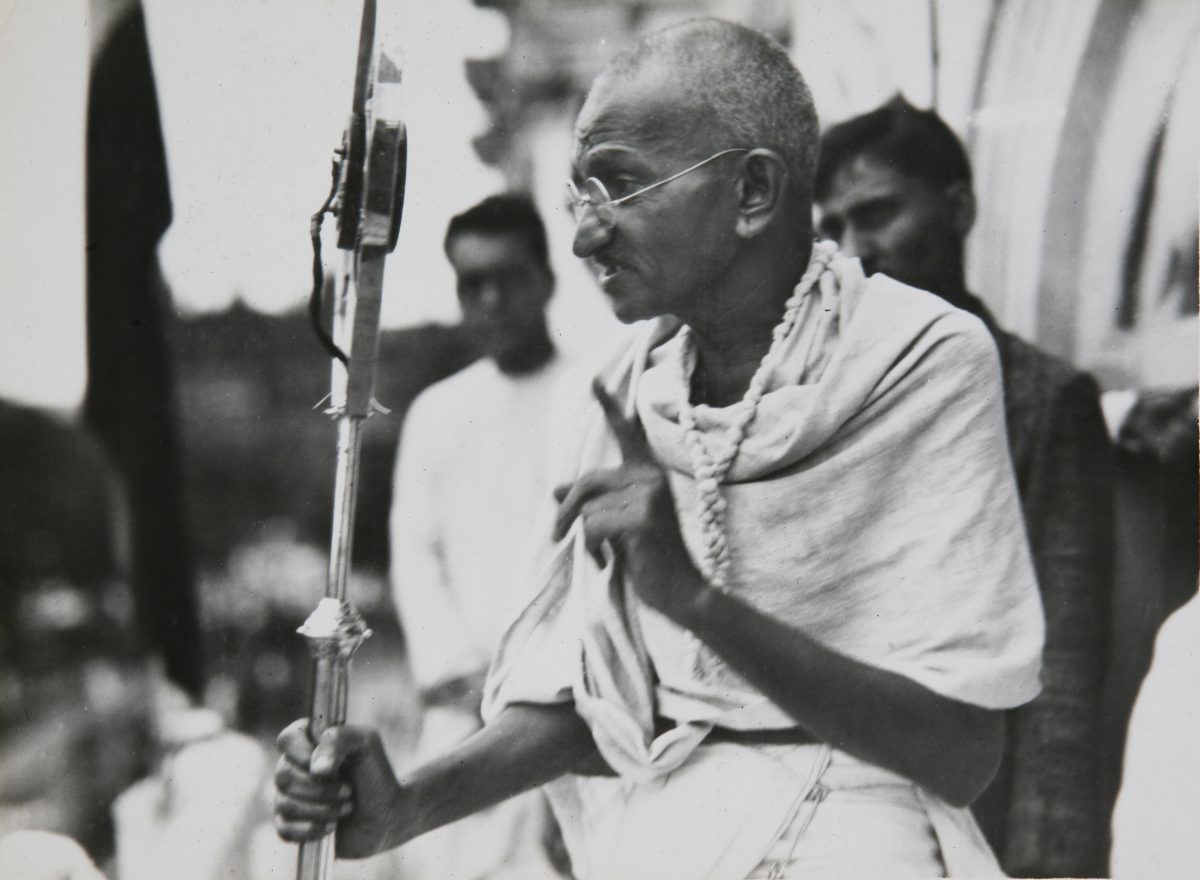

Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘A Guide to Health’

An excerpt, translated from Hindi by A. RAMA IYER, M.A.For more than twenty years past I have been paying special attention to the question of Health. While in England, I had to make my own arrangements for food and drink, and I can say, therefore, that my experience is quite reliable. I have arrived at certain definite conclusions from that experience, and I now set them down for the benefit of my readers. As the familiar saying goes, ‘Prevention is better than cure.’ It is far easier and safer to prevent illness by the observance of the laws of health than to set about curing the illness which has been brought on by our own ignorance and carelessness. Hence it is the duty of all thoughtful men to understand aright the laws of health, and the object of the following pages is to give an account of these laws. We shall also consider the best methods of cure for some of the most common diseases. There is nothing so closely connected with us as our body, but there is also nothing perhaps of which our ignorance is so profound, or our indifference so complete. As Milton says, the mind can make a hell of heaven or a heaven of hell. So heaven is not somewhere above the clouds, and hell somewhere underneath the earth! We have this same idea expressed in the Sanskrit saying, Mana êva Manushayanâm Kâranam Bandha Mokshayoh—man’s captivity or freedom is dependant on the state of his mind. From this it follows that whether a man is healthy or unhealthy depends on himself. Illness is the result not only of our actions but also of our thoughts. As has been said by a famous doctor, more people die for fear of diseases like small-pox, cholera and plague than out of those diseases themselves. Ignorance is one of the root-causes of disease. Very often we get bewildered at the most ordinary diseases out of sheer ignorance, and in our anxiety to get better, we simply make matters worse. Our ignorance of the most elementary laws of health leads us to adopt wrong remedies or drives us into the hands of the veriest quacks. How strange (and yet how true) it is that we know much less about things near at hand than things at a distance. We know hardly anything of our own village, but we can give by rote the names of the rivers and mountains of England! We take so much trouble to learn the names of the stars in the sky, while we hardly think it worth while to know the things that are in our own homes! We never care a jot for the splendid pageantry of Nature before our very eyes, while we are so anxious to witness the puerile mummeries of the theatre! And in the same way, we are not ashamed to be ignorant of the structure of our body, of the way in which the bones and muscles, grow, how the blood circulates and is rendered impure, how we are affected by evil thoughts and passions, how our mind travels over illimitable spaces and times while the body is at rest, and so on. There is nothing so closely connected with us as our body, but there is also nothing perhaps of which our ignorance is so profound, or our indifference so complete. But remember, above all, that the curing of your disease does not rest ultimately in the hands of any doctor. It is the duty of every one of us to get over this indifference. Everyone should regard it as his bounden duty to know something of the fundamental facts concerning his body. This kind of instruction should indeed be made compulsory in our schools. At present, we know not how to deal with the most ordinary scalds and wounds; we are helpless if a thorn runs into our foot; we are beside ourselves with fright and dismay if we are bitten by an ordinary snake! Indeed, if we consider the depth of our ignorance in such matters, we shall have to hang down our heads in shame. To assert that the average man cannot be expected to know these things is simply absurd. The following pages are intended for such as are willing to learn. I do not pretend that the facts mentioned by me have not been said before. But my readers will find here in a nutshell the substance of several books on the subject. I have arrived at my conclusions after studying these books, and after a series of careful experiments. Moreover, those who are new to this subject will also be saved the risk of being confounded by the conflicting views held by writers of such books. One writer says for instance, that hot water is to be used under certain circumstances, while another writer says that, exactly under the same circumstances, cold water is to be used. Conflicting views of this kind have been carefully considered by me, so that my readers may rest assured of the reliability of my own views. We have got into the habit of calling in a doctor for the most trivial diseases. Where there is no regular doctor available, we take the advice of mere quacks. We labour under the fatal delusion that no disease can be cured without medicine. This has been responsible for more mischief to mankind than any other evil. It is of course, necessary

An excerpt, translated from Hindi by A. RAMA IYER, M.A.

For more than twenty years past I have been paying special attention to the question of Health. While in England, I had to make my own arrangements for food and drink, and I can say, therefore, that my experience is quite reliable. I have arrived at certain definite conclusions from that experience, and I now set them down for the benefit of my readers.

As the familiar saying goes, ‘Prevention is better than cure.’ It is far easier and safer to prevent illness by the observance of the laws of health than to set about curing the illness which has been brought on by our own ignorance and carelessness. Hence it is the duty of all thoughtful men to understand aright the laws of health, and the object of the following pages is to give an account of these laws. We shall also consider the best methods of cure for some of the most common diseases.

There is nothing so closely connected with us as our body, but there is also nothing perhaps of which our ignorance is so profound, or our indifference so complete.

As Milton says, the mind can make a hell of heaven or a heaven of hell. So heaven is not somewhere above the clouds, and hell somewhere underneath the earth! We have this same idea expressed in the Sanskrit saying, Mana êva Manushayanâm Kâranam Bandha Mokshayoh—man’s captivity or freedom is dependant on the state of his mind. From this it follows that whether a man is healthy or unhealthy depends on himself. Illness is the result not only of our actions but also of our thoughts. As has been said by a famous doctor, more people die for fear of diseases like small-pox, cholera and plague than out of those diseases themselves.

Ignorance is one of the root-causes of disease. Very often we get bewildered at the most ordinary diseases out of sheer ignorance, and in our anxiety to get better, we simply make matters worse. Our ignorance of the most elementary laws of health leads us to adopt wrong remedies or drives us into the hands of the veriest quacks. How strange (and yet how true) it is that we know much less about things near at hand than things at a distance. We know hardly anything of our own village, but we can give by rote the names of the rivers and mountains of England! We take so much trouble to learn the names of the stars in the sky, while we hardly think it worth while to know the things that are in our own homes! We never care a jot for the splendid pageantry of Nature before our very eyes, while we are so anxious to witness the puerile mummeries of the theatre! And in the same way, we are not ashamed to be ignorant of the structure of our body, of the way in which the bones and muscles, grow, how the blood circulates and is rendered impure, how we are affected by evil thoughts and passions, how our mind travels over illimitable spaces and times while the body is at rest, and so on. There is nothing so closely connected with us as our body, but there is also nothing perhaps of which our ignorance is so profound, or our indifference so complete.

But remember, above all, that the curing of your disease does not rest ultimately in the hands of any doctor.

It is the duty of every one of us to get over this indifference. Everyone should regard it as his bounden duty to know something of the fundamental facts concerning his body. This kind of instruction should indeed be made compulsory in our schools. At present, we know not how to deal with the most ordinary scalds and wounds; we are helpless if a thorn runs into our foot; we are beside ourselves with fright and dismay if we are bitten by an ordinary snake! Indeed, if we consider the depth of our ignorance in such matters, we shall have to hang down our heads in shame. To assert that the average man cannot be expected to know these things is simply absurd. The following pages are intended for such as are willing to learn.

I do not pretend that the facts mentioned by me have not been said before. But my readers will find here in a nutshell the substance of several books on the subject. I have arrived at my conclusions after studying these books, and after a series of careful experiments. Moreover, those who are new to this subject will also be saved the risk of being confounded by the conflicting views held by writers of such books. One writer says for instance, that hot water is to be used under certain circumstances, while another writer says that, exactly under the same circumstances, cold water is to be used. Conflicting views of this kind have been carefully considered by me, so that my readers may rest assured of the reliability of my own views.

We have got into the habit of calling in a doctor for the most trivial diseases. Where there is no regular doctor available, we take the advice of mere quacks. We labour under the fatal delusion that no disease can be cured without medicine. This has been responsible for more mischief to mankind than any other evil. It is of course, necessary that our diseases should be cured, but they cannot be cured by medicines. Not only are medicines merely useless, but at times even positively harmful. For a diseased man to take drugs and medicines would be as foolish as to try to cover up the filth that has accumulated in the inside of the house. The more we cover up the filth, the more rapidly does putrefaction go on. The same is the case with the human body. Illness or disease is only Nature’s warning that filth has accumulated in some portion or other of the body; and it would surely be the part of wisdom to allow Nature to remove the filth, instead of covering it up by the help of medicines. Those who take medicines are really rendering the task of Nature doubly difficult. It is, on the other hand, quite easy for us to help Nature in her task by remembering certain elementary principles,—by fasting, for instance, so that the filth may not accumulate all the more, and by vigorous exercise in the open air, so that some of the filth may escape in the form of perspiration. And the one thing that is supremely necessary is to keep our minds strictly under control.

We find from experience that, when once a bottle of medicine gets itself introduced into a home, it never thinks of going out, but only goes on drawing other bottles in its train. We come across numberless human beings who are afflicted by some disease or other all through their lives in spite of their pathetic devotion to medicines. They are to-day under the treatment of this doctor, to-morrow of that. They spend all their life in a futile search after a doctor who will cure them for good. As the late Justice Stephen (who was for some time in India) said, it is really astonishing that drugs of which so little is known should be applied by doctors to bodies of which they know still less! Some of the greatest doctors of the West themselves have now come to hold this view. Sir Astley Cooper, for instance, admits that the ‘science’ of medicine is mostly mere guess-work; Dr. Baker and Dr. Frank hold that more people die of medicines than of diseases; and Dr. Masongood even goes to the extent of saying that more men have fallen victims to medicine than to war, famine and pestilence combined!

It is also a matter of experience that diseases increase in proportion to the increase in the number of doctors in a place. The demand for drugs has become so widespread that even the meanest papers are sure of getting advertisements of quack medicines, if of nothing else. In a recent book on the Patent Medicines we are told that the Fruit-salts and syrups, for which we pay from Rs. 2 to Rs. 5, cost to their manufacturers only from a quarter of an anna to one anna! No wonder, then, that their compositions should be so scrupulously kept a secret.

We will, therefore, assure our readers that there is absolutely no necessity for them to seek the aid of doctors. To those, however, who may not be willing to boycott doctors and medicines altogether, we will say, “As far as possible, possess your souls in patience, and do not trouble the doctors. In case you are forced at length to call in the aid of a doctor, be sure to get a good man; then, follow his directions strictly, and do not call in another doctor, unless by his own advice. But remember, above all, that the curing of your disease does not rest ultimately in the hands of any doctor.”

The Meaning of Health

Ordinarily that man is considered healthy who eats well and moves about, and does not resort to a doctor. But a little thought will convince us that this idea is wrong. There are many cases of men being diseased, in spite of their eating well and freely moving about. They are under the delusion that they are healthy, simply because they are too indifferent to think about the matter.

In fact, perfectly healthy men hardly exist anywhere over this wide world.

As has been well said, only that man can be said to be really healthy, who has a sound mind in a sound body. The relation between the body and the mind is so intimate that, if either of them got out of order, the whole system would suffer. Let us take the analogy of the rose-flower. Its colour stands to its fragrance in the same way as the body to the mind or the soul. No one regards an artificial paper-flower as a sufficient substitute for the natural flower, for the obvious reason that the fragrance, which forms the essence of the flower, cannot be reproduced. So too, we instinctively honour the man of a pure mind and a noble character in preference to the man who is merely physically strong. Of course, the body and the soul are both essential, but the latter is far more important than the former. No man whose character is not pure can be said to be really healthy. The body which contains a diseased mind can never be anything but diseased. Hence it follows that a pure character is the foundation of health in the real sense of the term; and we may say that all evil thoughts and evil passions are but different forms of disease.

Thus considered, we may conclude that that man alone is perfectly healthy whose body is well formed, whose teeth as well as eyes and ears are in good condition, whose nose is free from dirty matter, whose skin exudes perspiration freely and without any bad smell, whose mouth is also free from bad smells, whose hands and legs perform their duty properly, who is neither too fat nor too thin, and whose mind and senses are constantly under his control. As has already been said, it is very hard to gain such health, but it is harder still to retain it, when once it has been acquired. The chief reason why we are not truly healthy is that our parents were not. An eminent writer has said that, if the parents are in perfectly good condition their children would certainly be superior to them in all respects. A perfectly healthy man has no reason to fear death; our terrible fear of death shows that we are far from being so healthy. It is, however, the clear duty of all of us to strive for perfect health. We will, therefore, proceed to consider in the following pages how such health can be attained, and how, when once attained, it can also be retained for ever.

The Human Body

The world is compounded of the five elements,—earth, water, air, fire, and ether. So too is our body. It is a sort of miniature world. Hence the body stands in need of all the elements in due proportion,—pure earth, pure water, pure fire or sunlight, pure air, and open space. When any one of these falls short of its due proportion, illness is caused in the body.

The body is made up of skin and bone, as well as flesh and blood. The bones constitute the frame-work of the body; but for them we could not stand erect and move about. They protect the softer parts of the body. Thus the skull gives protection to the brain, while the ribs protect the heart and the lungs. Doctors have counted 238 bones in the human body. The outside of the bones is hard, but the inside is soft and hollow. Where there is a joint between two bones, there is a coating of marrow, which may be regarded as a soft bone. The teeth, too, are to be counted among the bones.

When we feel the flesh at some points, we find it to be tough and elastic. This part of the flesh is known as the muscle. It is the muscles that enable us to fold and unfold our arms, to move our jaws, and to close our eyes. It is by means of the muscles, again, that our organs of perception do their work.

It is beyond the province of this book to give a detailed account of the structure of the body; nor has the present writer enough knowledge to give such an account. We will, therefore, content ourselves with just as much information as is essential for our present purpose.

The most important portion of the body is the stomach. If the stomach ceases to work even for a single moment, the whole body would collapse. The work of the stomach is to digest the food, and so to provide nourishment to the body. Its relation to the body is the same as that of the steam engine to the Railway train. The gastric juice which is produced in the stomach helps the assimilation of nutritious elements in the food, the refuse being sent out by way of the intestines in the form of urine and fæces. On the left side of the abdominal cavity is the spleen, while to the right of the stomach is the liver, whose function is the purification of the blood and the secretion of the bile, which is so useful for digestion.

In the hollow space enclosed by the ribs are situated the heart and the lungs. The heart is between the two lungs, but more to the left than the right. There are on the whole 24 bones in the chest; the action of the heart can be felt between the fifth and the sixth rib. The lungs are connected with the windpipe. The air which we inhale is taken into the lungs through the windpipe, and the blood is purified by it. It is of the utmost importance to breathe through the nose, instead of through the mouth.

On the circulation of the blood depend all activities of the body. It is the blood that provides nourishment to the body. It extracts the nutritious elements out of the food, and ejects the refuse through the intestines, and so keeps the body warm. The blood is incessantly circulating all over the body, along the veins and the arteries. [Pg 14]The beatings of the pulse are due to the circulation of the blood. The pulse of a normal adult man beats some 75 times a minute. The pulses of children beat faster, while those of old men are slower.

The chief agency for keeping the blood pure is the air. When the blood returns to the lungs after one complete round over the body, it is impure and contains poisonous elements. The oxygen of the air which we inhale purifies this blood and is assimilated into it, while the nitrogen absorbs the poisonous matter and is breathed out. This process goes on incessantly. As the air has a very important function to perform in the body, we shall devote a separate chapter to a detailed consideration of the same.

Thoughts

One question which I have asked myself again and again, in the course of writing this book, is why I of all persons should write it. Is there any justification at all for one like me, who am no doctor, and whose knowledge of the matters dealt with in these pages must be necessarily imperfect, attempting to write a book of this kind?

My defence is this. The “science” of medicine is itself based upon imperfect knowledge, most of it being mere quackery. But this book, at any rate, has been prompted by the purest of motives. The attempt is here made not so much to show how to cure diseases as to point out the means of preventing them. And a little reflection will show that the prevention of disease is a comparatively simple matter, not requiring much specialist knowledge, although it is by no means an easy thing to put these principles into practice. Our object has been to show the unity of origin and treatment of all diseases, so that all people may [Pg 143]learn to treat their diseases themselves when they do arise, as they often do, in spite of great care in the observance of the laws of health.

But, after all, why is good health so essential, so anxiously to be sought for? Our ordinary conduct would seem to indicate that we attach little value to health. If health is to be sought for in order that we might indulge in luxury and pleasure, or pride ourselves over our body and regard it as an end in itself, then indeed it would be far better that we should have bodies tainted with bad blood, by fat, and the like.

All religions agree in regarding the human body as an abode of God. Our body has been given to us on the understanding that we should render devoted service to God with its aid. It is our duty to keep it pure and unstained from within as well as from without, so as to render it back to the Giver, when the time comes for it, in the state of purity in which we got it. If we fulfil the terms of the contract to God’s satisfaction, He will surely reward us, and make us heirs to immortality.

The bodies of all created beings have been gifted with the same senses, and the same capacity for seeing, hearing, smelling and the like; but the human body is supreme among them all, and hence we call it a “Chintamani,” or [Pg 144]a giver of all good. Man alone can worship God with knowledge and understanding. Where devotion to God is void of understanding, there can be no true salvation, and without salvation there can be no true happiness. The body can be of real service only when we realise it to be a temple of God and make use of it for God’s worship; otherwise it is no better than a filthy vessel of bones, flesh and blood, and the air and water issuing from it are worse than poison. The things that come out of the body through the pores and other passages are so filthy that we cannot touch them or even think of them without disgust; and it requires very great effort to keep them tolerably clean. Is it not most disgraceful that, for the sake of this body, we should stoop to falsehood and deceit, licentious practices and even worse? Is it not equally shameful that, for the sake of these vices, we should be so anxious to preserve this fragile frame of ours at any cost?

This is the truth of the matter in regard to our body; for the very things which are the best or the most useful have inherent in them capabilities of a corresponding mischief. Otherwise, we should hardly be able to appreciate them at their true worth. The light of the sun, which is the source of our life, and without which we cannot live for an hour, is also capable [Pg 145]of burning all things to ashes. So too, a king may do infinite good to his subjects, or be the source of untold mischief. Indeed, the body may be a good servant, but, when it becomes a master, its powers of evil are unlimited.

There is an incessant struggle going on within us between our Soul and Satan for the control of our body. If the soul gains the ascendancy, the body becomes a most potent instrument of good; but, if the devil is victorious in the struggle, it becomes a hot-bed of vice. Hell itself would be preferable to the body which is the slave of vice, which is constantly filled with decaying matter and which emits filthy odours, whose hands and feet are employed in unworthy deeds, whose tongue is employed in eating things that ought not to be eaten or in uttering language that ought not to be uttered, whose eyes are employed in seeing things that ought not to be seen, whose ears are employed in the hearing of things that ought not to be heard, and whose nose is employed in the smelling of things that ought not to be smelt. But, while hell is never mistaken for heaven by anybody, our body which is rendered worse than hell by ourselves is, strangely enough, regarded by us as almost heavenly! So monstrous is our vanity, and so pitiful our pride, in this matter! Those who make use of a palace as a [Pg 146]latrine, or vice versa, must certainly reap the fruit of their folly. So too, if, while our body is really in the Devil’s hands, we should fancy that we are enjoying true health, we shall have only ourselves to thank for the terrible consequences that are sure to follow.

To conclude, then our attempt in these pages has been to teach the great truth that perfect health can be attained only by living in obedience to the laws of God, and defying the power of Satan. True happiness is impossible without true health, and true health is impossible without a rigid control of the palate. All the other senses will automatically come under our control when the palate has been brought under control. And he who has conquered his senses has really conquered the whole world, and he becomes a part of God. We cannot realise Rama by reading the Ramayana, or Krishna by reading the Gita, or God by reading the Koran, or Christ by reading the Bible; the only means of realising them is by developing a pure and noble character. Character is based on virtuous action, and virtuous action is grounded on Truth. Truth, then, is the source and foundation of all things that are good and great. Hence, a fearless and unflinching pursuit of the ideal of Truth and Righteousness is the key-note of true health as of all else. And if we have succeeded (in however [Pg 147]feeble a measure) in bringing this grand fact home to our reader, our object in writing these pages would have been amply fulfilled.