How Communism Led to Fascism and Violence

A book review of 'The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II'Commentary Communism is an ideology supposedly meant to achieve equality and peace. Still, in reality, its promotion of dictatorship and violent takeover of the means of production have invariably led to some of the world’s worst authoritarian regimes. As a result, tens of millions were killed in wars, famines, and genocides, including against Koreans, Afghans, Chechens, Ukrainians, Vietnamese, Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Falun Gong adherents. Less commonly understood is how communist revolutions, including the original one in Russia in 1917, and its epigones throughout Europe and Asia, provoked the fascist overreaction that led to social and racist violence in interwar Italy and Germany, and appeasement by Britain and Eastern European countries that paved the way for war and genocide by the Nazis. Into this breach steps Jonathan Haslam’s informative new book, “The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II” (Princeton University Press, 2021). Haslam is a professor at Cambridge University in Britain and used archives throughout Europe for his study. Ideology of Communism Shortly after the Russian Revolution and World War I, British journalists began noticing what they called “Bolshevist imperialism,” or the drive to export communism from Russia to the globe. Not just Russians suffered under communism, they noted. The world risked falling to its invading armies, domestic and foreign. The communist ideology of Marxism-Leninism (then inaccurately known by the self-description of “Bolshevism” or “those of the majority”) was key to Russia’s imperialism—as Russia was a weak state relative to its peers—and so dependent upon foreign workers and peasants who Bolshevists claimed would benefit from the violent overthrow of capitalism. This “working class” was susceptible to the communist ideology that falsely claimed it would “liberate” them from their “chains.” Russian dictator and communist leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin makes a celebratory speech as head of the first Soviet government in Red Square on the first anniversary of the 1917 Russian Revolution on Nov. 7, 1918. (P Otsup/Getty Images) Bolshevist propaganda was so successful by 1918, according to Switzerland’s ambassador to France, that “Everywhere there are disturbances, riots and convulsions.” Democracies could only survive in these conditions, according to Haslam, “through making extravagant empty promises of social reform—in Britain’ homes for heroes’ that were never built—and of more egalitarian income distribution, delaying the inevitable moment when these promissory notes would fall due in the likelihood that the means for delivering on them would be insufficient to meet pressing demand.” Origin of Italian Fascism In the context of growing communist unrest in interwar Italy, government corruption of both the political and financial varieties led to a “chronically weak” democracy, according to Haslam. “As the hard left pressed upon them, they succumbed bit by bit,” he writes. “As they did so, countervailing resentment grew slowly but resolutely at the local level, inflamed by the right.” By 1919, an ultranationalist movement emerged in Italy “as leagues of ex-combatants [from World War I] reacted violently when socialist anti-militarists blocked the erection of monuments to commemorate the war dead, pouring scorn on those who wore decorations for service to their country.” In response to “unremitting intimidation from the far left,” according to Haslam, and just three years after the Russian Revolution, Italy had its first general assembly in 1920 of an emerging fascist movement. The early Italian fascists were against the League of Nations and the financial dominance of their country. They opposed disruptive “waves of strikes in the cities of Rome, Naples, Turin, Milan and Genoa on the trams and railways, among taxi drivers and in the post office and electrical services; matched by those of agricultural labourers in Apulia, Emilia-Romagna and the Veneto,” writes Haslam. Inflation and violence resulted from communist unrest, hurting the political and financial stability of not only Italian property owners, but also pensioners, administrative workers, and those on fixed incomes. Meanwhile, “the rest of Europe panicked as [the Russian] Red Army swept across Poland, heading for Warsaw in August [1920], possibly with Berlin to follow,” Haslam writes. From this rapid expansion of communism—and ineffectual response from established forms of democratic governance—came the perceived need for strongmen in democracies, including Benito Mussolini in Italy. Nazi Germany Fascism, and its violent, racist, opportunistic, and authoritarian overreaction to the like violence, opportunism, and authoritarianism of a communist ideology that would ultimately become racist as well, grew under these conditions and persisted as Adolf Hitler t

A book review of 'The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II'

Commentary

Communism is an ideology supposedly meant to achieve equality and peace. Still, in reality, its promotion of dictatorship and violent takeover of the means of production have invariably led to some of the world’s worst authoritarian regimes.

As a result, tens of millions were killed in wars, famines, and genocides, including against Koreans, Afghans, Chechens, Ukrainians, Vietnamese, Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Falun Gong adherents.

Less commonly understood is how communist revolutions, including the original one in Russia in 1917, and its epigones throughout Europe and Asia, provoked the fascist overreaction that led to social and racist violence in interwar Italy and Germany, and appeasement by Britain and Eastern European countries that paved the way for war and genocide by the Nazis.

Into this breach steps Jonathan Haslam’s informative new book, “The Spectre of War: International Communism and the Origins of World War II” (Princeton University Press, 2021). Haslam is a professor at Cambridge University in Britain and used archives throughout Europe for his study.

Ideology of Communism

Shortly after the Russian Revolution and World War I, British journalists began noticing what they called “Bolshevist imperialism,” or the drive to export communism from Russia to the globe. Not just Russians suffered under communism, they noted. The world risked falling to its invading armies, domestic and foreign.

The communist ideology of Marxism-Leninism (then inaccurately known by the self-description of “Bolshevism” or “those of the majority”) was key to Russia’s imperialism—as Russia was a weak state relative to its peers—and so dependent upon foreign workers and peasants who Bolshevists claimed would benefit from the violent overthrow of capitalism. This “working class” was susceptible to the communist ideology that falsely claimed it would “liberate” them from their “chains.”

Bolshevist propaganda was so successful by 1918, according to Switzerland’s ambassador to France, that “Everywhere there are disturbances, riots and convulsions.”

Democracies could only survive in these conditions, according to Haslam, “through making extravagant empty promises of social reform—in Britain’ homes for heroes’ that were never built—and of more egalitarian income distribution, delaying the inevitable moment when these promissory notes would fall due in the likelihood that the means for delivering on them would be insufficient to meet pressing demand.”

Origin of Italian Fascism

In the context of growing communist unrest in interwar Italy, government corruption of both the political and financial varieties led to a “chronically weak” democracy, according to Haslam. “As the hard left pressed upon them, they succumbed bit by bit,” he writes. “As they did so, countervailing resentment grew slowly but resolutely at the local level, inflamed by the right.”

By 1919, an ultranationalist movement emerged in Italy “as leagues of ex-combatants [from World War I] reacted violently when socialist anti-militarists blocked the erection of monuments to commemorate the war dead, pouring scorn on those who wore decorations for service to their country.”

In response to “unremitting intimidation from the far left,” according to Haslam, and just three years after the Russian Revolution, Italy had its first general assembly in 1920 of an emerging fascist movement.

The early Italian fascists were against the League of Nations and the financial dominance of their country. They opposed disruptive “waves of strikes in the cities of Rome, Naples, Turin, Milan and Genoa on the trams and railways, among taxi drivers and in the post office and electrical services; matched by those of agricultural labourers in Apulia, Emilia-Romagna and the Veneto,” writes Haslam.

Inflation and violence resulted from communist unrest, hurting the political and financial stability of not only Italian property owners, but also pensioners, administrative workers, and those on fixed incomes.

Meanwhile, “the rest of Europe panicked as [the Russian] Red Army swept across Poland, heading for Warsaw in August [1920], possibly with Berlin to follow,” Haslam writes.

From this rapid expansion of communism—and ineffectual response from established forms of democratic governance—came the perceived need for strongmen in democracies, including Benito Mussolini in Italy.

Nazi Germany

Fascism, and its violent, racist, opportunistic, and authoritarian overreaction to the like violence, opportunism, and authoritarianism of a communist ideology that would ultimately become racist as well, grew under these conditions and persisted as Adolf Hitler turned fascism toward his territorially expansionist and genocidal purposes.

“Entire countries, including Poland, Romania and Czechoslovakia, were all the more easily isolated, picked off one by one and then wiped off the map by Hitler because for each of them the dread of Communist rule ultimately proved greater than the fear of the Nazis,” writes Haslam.

At that time, he notes, the threat from the Soviet Union was well known, including in Britain. Not so much, “the scale and depth of that looming from … Nazi Germany.”

British officials, who subscribed to classical economics, hoped to thwart the threats of both communism and fascism through diplomatic pressure and that very British strength, international trade. But Russia did not “miraculously” evolve, as was hoped. Neither, for that matter, did Nazi Germany.

The Comintern Provokes Appeasement

This British insouciance persisted in the face of communist and fascist unrest, despite the founding of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1919 to promote revolutions globally, with the additional requirement in 1920 that they fully obey Moscow.

Haslam accessed Comintern archives for his book.

In 1921, the Comintern directly supported the foundation of the Chinese Communist Party, for example, which threatened British interests in the country.

The Bolsheviks in China “based their activities around existing student discussion groups, from which they helped build Communist organisations in Beijing, Shanghai, Tientsin, Canton, Hankow, Nanjing and elsewhere,” according to Haslam.

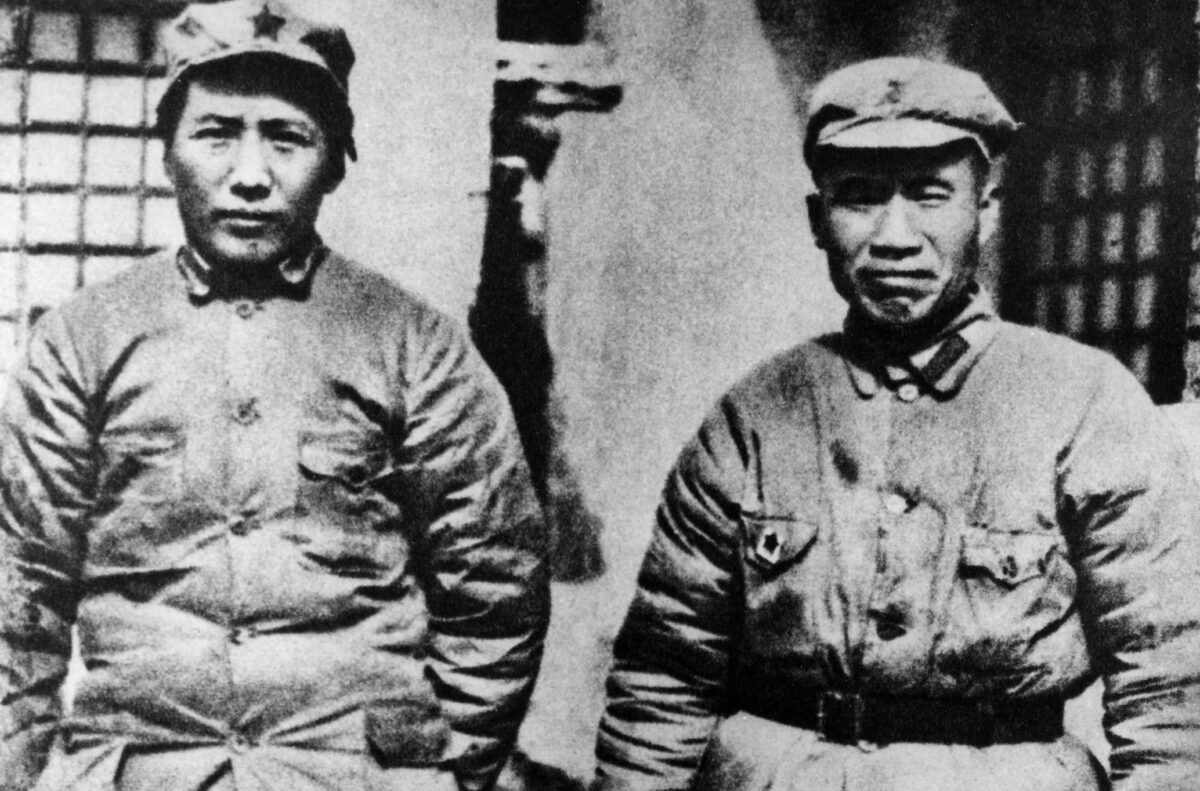

Soviet propaganda poured into China, seen as the weakest link in “global capitalism.” It inspired unrest and revolution of overlapping nationalist, racial, and communist varieties in the 1920s against warlords and foreigners, including the British. Nationalists and communists fought a civil war in China between 1927 and 1936, but were otherwise relatively united in their attempts to drive out foreign “imperialism.”

“Even when insurrectionist régimes display a steadfast determination to undermine the workings of the entire international system, the [British] tendency has invariably been to assume that ‘common sense’ will sooner or later return and reaffirm its natural dominance,” writes Haslam, who notes that the British call this “watchful waiting” while Americans call it “strategic patience.”

In 1936, “Bolshevism was back in Europe, spearheaded by Comintern’s Popular Front in France and Spain,” according to Haslam.

“Mussolini was assumed [by British officials] to be fundamentally sound at home where he kept Bolshevism in its place and Gramsci [the Italian communist] in prison, though provocative in his foreign ambitions.”

“Hitler’s breaches of the Versailles Treaty, even the reoccupation of the Rhineland, were seen [by the British] as the necessary rectification of recent injustices; fascism in Germany, as in Italy and then in Spain, was viewed as a necessary antidote to revolutionary excesses.”

While former British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain is typically portrayed as weak, which ostensibly led to his appeasement of Hitler, Haslam portrays him as a closet anti-semite and admirer of strongmen like Hitler and Mussolini.

Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler is portrayed not so much as a weakness, but as a hidden ideological agreement with fascism as an antidote to communism, and a racist and wilful ignorance of its atrocities.

An off-the-record briefing by Chamberlain appears in the book in which a reporter recalled, “Any questions put across the table about, say, reports of persecutions of Jews, Hitler’s broken pledges or Mussolini’s ambitions, would receive a response on well-established lines; he was surprised that such an experienced journalist was susceptible to Jewish-Communist propaganda.”

Relevance to Today

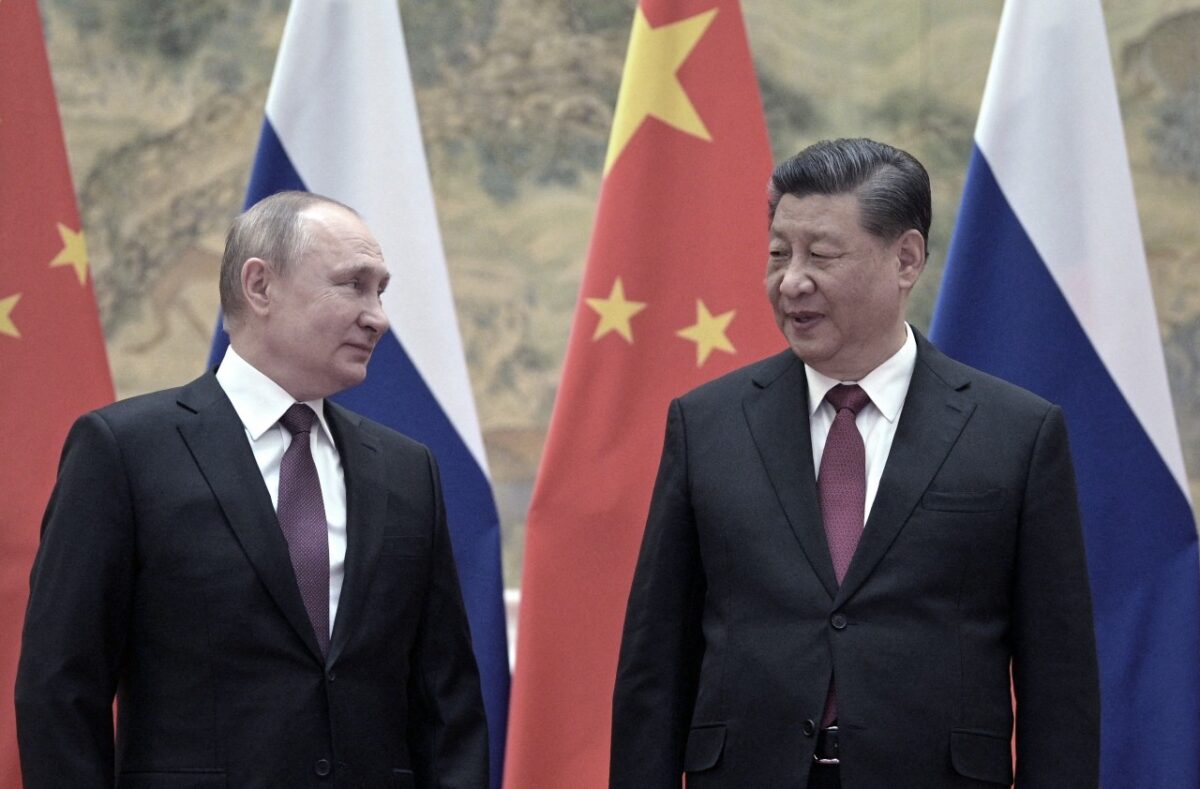

Today it is not Hitler and Mussolini who threaten war and take territory, but Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. The latter are just as racist, against Ukrainians, Uyghurs, and Tibetans, for example.

Given China’s massive economy and utilization of sophisticated surveillance technology, this renewed Russian-Chinese axis of totalitarians, however, is arguably even more dangerous than those of the 20th century.

Both China and Russia seek to exploit political polarization in the United States and Europe to make the legislator on the other side of the aisle seem more of a threat than the dictator across the oceans.

As the parallels above should demonstrate, there is again the risk of democracies overreacting to domestic political differences and transforming their own societies into those they set themselves against dictatorship and war. Haslam’s book is a good way to remind ourselves of the common goals we have as Americans, the dangers of both communism and fascism, and how these extreme ideologies feed upon each other. Let’s hope the book is read and helps us avoid both dangers in the future.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.