Going Nuclear in Asia: More Than Just Building a Bomb

Commentary Could America’s Asian allies go nuclear? This is a recurring scenario, given continuing concerns in Tokyo, Seoul, and even Canberra that Washington’s security commitment to Asia—and particularly its promise of extended nuclear deterrence—may be less than dependable. In articles (found here, here, and here), the argument is made that countries like Japan, South Korea, and Australia should consider hedging their bets and building their own nuclear force. Analysis such as Walter Russell Mead has gone so far as to argue that some “America Firsters,” such as former President Donald Trump, might even welcome the idea of a nuclearized Asia. Removing our Asian allies from the U.S. nuclear umbrella might please those who feel these countries should be doing more (and asking Washington to do less) for their own defense. It is generally acknowledged that Japan has the technological capacity to build an atomic bomb in a relatively short time—months, perhaps, a few years at the most. South Korea and Australia might not take much longer. (Indeed, Canberra seriously looked into the idea of building its own nuclear weapons in the 1950s and 1960s). If these were to build a nuclear bomb and test it, it would have resonance throughout Asia and, indeed, the rest of the world. The challenge is not necessarily in building an atomic bomb, however, but all the other things that come along with it that are necessary to create a credible nuclear deterrent. Becoming a nuclear-weapons state is a lot harder than one might think. First, a country needs to test and retest its nuclear capabilities. Ultimately these countries would probably have to conduct several tests over several years to ensure a reliable nuclear force. And where would they conduct these tests? Australia has lots of open lands, but many Japanese would likely object to testing (even underground) on national territory. Second, how to deploy such a weapon? Aircraft would be an obvious choice, but Japan, South Korea, and Australia possess no nuclear-capable aircraft, bombers, or specialized strike aircraft. Canberra retired its medium-range bomber force (the F-111C) more than a dozen years ago. All three countries operate the F-35 fighter, which is being tested to carry nuclear weapons, but the United States may be loath to modify these countries’ F-35s (which means opening up the sealed “black boxes”) for this purpose. U.S. military personnel work near an F-35 fighter jet of the Vermont Air National Guard, parked in the military base at Skopje Airport, North Macedonia, on June 17, 2022. (Boris Grdanoski/AP Photo) Another option is putting nuclear weapons on missiles. That would require miniaturizing a nuclear weapon to fit on a missile and then developing the missile itself. For most countries, a specialized solid-fueled missile would have to be built almost from scratch. Where then would these countries put these missiles, whether in silos (which in Japan would be vulnerable to earthquakes) or on mobile launchers? Heavily populated countries like Japan and South Korea will likely see considerable local pushback over deploying such weapons in their neighborhoods, given that they would be high-value targets for an enemy’s first strike. The most likely solution would be to deploy these missiles on submarines. That would, in turn, require a specialized submarine-launched missile encapsulated for underwater launch, and perhaps even a new submarine. If these submarines were nuclear-powered (SSBN), it would mean coming to another technological hurdle (small, extremely safe nuclear reactors). (That said, South Korea is already testing such a submarine-launched missile, while Australia is planning on acquiring nuclear-powered submarines in cooperation with the United States and Great Britain.) Above all, all this would not be cheap. It is costing Britain £31 billion (nearly $39 billion) to create a four-boat fleet of Dreadnought-class SSBNs—and London simply bought submarine-launched Trident II missiles off the shelf from the United States (something Washington would likely not do for its Asian allies). At the same time, these countries would have to build up a whole supporting infrastructure for nuclear weapons. Specialized, extremely secure storage facilities would have to be built at airbases and naval stations to secure them. Nuclear engineers would have to be trained to maintain and handle these bombs and warheads. These countries would also have to come up with a specialized command and control to safeguard the use of nuclear forces. Security devices called permissive action links (PALs) would have to be fitted to each weapon to prevent the unauthorized arming or detonation of a nuclear device. Such PALs would have to be highly encrypted to avoid being hacked. Tokyo, Seoul, and Canberra would then have to devise protocols for arming and using their nuclear forces. Most likely, the president or prime minister would control the “nuclear football” c

Commentary

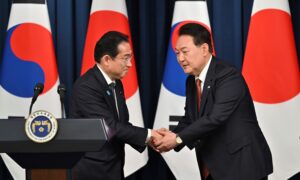

Could America’s Asian allies go nuclear? This is a recurring scenario, given continuing concerns in Tokyo, Seoul, and even Canberra that Washington’s security commitment to Asia—and particularly its promise of extended nuclear deterrence—may be less than dependable.

In articles (found here, here, and here), the argument is made that countries like Japan, South Korea, and Australia should consider hedging their bets and building their own nuclear force.

Analysis such as Walter Russell Mead has gone so far as to argue that some “America Firsters,” such as former President Donald Trump, might even welcome the idea of a nuclearized Asia. Removing our Asian allies from the U.S. nuclear umbrella might please those who feel these countries should be doing more (and asking Washington to do less) for their own defense.

It is generally acknowledged that Japan has the technological capacity to build an atomic bomb in a relatively short time—months, perhaps, a few years at the most. South Korea and Australia might not take much longer. (Indeed, Canberra seriously looked into the idea of building its own nuclear weapons in the 1950s and 1960s). If these were to build a nuclear bomb and test it, it would have resonance throughout Asia and, indeed, the rest of the world.

The challenge is not necessarily in building an atomic bomb, however, but all the other things that come along with it that are necessary to create a credible nuclear deterrent. Becoming a nuclear-weapons state is a lot harder than one might think.

First, a country needs to test and retest its nuclear capabilities. Ultimately these countries would probably have to conduct several tests over several years to ensure a reliable nuclear force. And where would they conduct these tests? Australia has lots of open lands, but many Japanese would likely object to testing (even underground) on national territory.

Second, how to deploy such a weapon? Aircraft would be an obvious choice, but Japan, South Korea, and Australia possess no nuclear-capable aircraft, bombers, or specialized strike aircraft. Canberra retired its medium-range bomber force (the F-111C) more than a dozen years ago. All three countries operate the F-35 fighter, which is being tested to carry nuclear weapons, but the United States may be loath to modify these countries’ F-35s (which means opening up the sealed “black boxes”) for this purpose.

Another option is putting nuclear weapons on missiles. That would require miniaturizing a nuclear weapon to fit on a missile and then developing the missile itself. For most countries, a specialized solid-fueled missile would have to be built almost from scratch.

Where then would these countries put these missiles, whether in silos (which in Japan would be vulnerable to earthquakes) or on mobile launchers? Heavily populated countries like Japan and South Korea will likely see considerable local pushback over deploying such weapons in their neighborhoods, given that they would be high-value targets for an enemy’s first strike.

The most likely solution would be to deploy these missiles on submarines. That would, in turn, require a specialized submarine-launched missile encapsulated for underwater launch, and perhaps even a new submarine. If these submarines were nuclear-powered (SSBN), it would mean coming to another technological hurdle (small, extremely safe nuclear reactors).

(That said, South Korea is already testing such a submarine-launched missile, while Australia is planning on acquiring nuclear-powered submarines in cooperation with the United States and Great Britain.)

Above all, all this would not be cheap. It is costing Britain £31 billion (nearly $39 billion) to create a four-boat fleet of Dreadnought-class SSBNs—and London simply bought submarine-launched Trident II missiles off the shelf from the United States (something Washington would likely not do for its Asian allies).

At the same time, these countries would have to build up a whole supporting infrastructure for nuclear weapons. Specialized, extremely secure storage facilities would have to be built at airbases and naval stations to secure them. Nuclear engineers would have to be trained to maintain and handle these bombs and warheads.

These countries would also have to come up with a specialized command and control to safeguard the use of nuclear forces. Security devices called permissive action links (PALs) would have to be fitted to each weapon to prevent the unauthorized arming or detonation of a nuclear device. Such PALs would have to be highly encrypted to avoid being hacked.

Tokyo, Seoul, and Canberra would then have to devise protocols for arming and using their nuclear forces. Most likely, the president or prime minister would control the “nuclear football” containing the launch codes, and he or she would be the final authority for the actual release of nuclear weapons. But what about submarine-launched nuclear forces? Even with the “two-man rule,” submarine commanders on SSBNs theoretically have considerable autonomy to launch on their own authority. Such details would have to be worked out.

Above all, these countries would need to tackle all of these technological and infrastructure issues on their own. The United States certainly is not going to help. Building a credible nuclear force would cost billions of dollars, and it would take decades to put it into place.

In the meantime, domestic opposition to “going nuclear” could be intense. One might expect the far right in both Japan and South Korea to love the idea. Japan’s ultra-conservative nationalists have long yearned for the day of reclaiming the country’s imperial heritage, of possessing a massive military force, including nuclear weapons, capable of defending the country independently. South Korea might follow suit simply to match the Japanese.

On the other hand, the vast majority of Japan’s population, which is still heavily anti-militarist, anti-war, and anti-nuclear, might be squeamish about the idea of a nuclear Japan. Liberal and left-wing forces in South Korea and Australia are also likely to oppose such a nuclearization, especially if it is perceived to destabilize regional security.

A nuclear Asia is not unimaginable. At the same time, it is not a thing that could be done on the cheap, in a hurry, or without provoking a massive political tempest.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.