Federal Financial Mess

CommentaryEven before the recent spate of spending legislation, the authoritative Congressional Budget Office (CBO) warned of the precarious state of Washington’s finances. Its figures show that the relentless growth in entitlements will push up budget deficits and add to the nation’s already heavy accumulation of public debt. By 2032, the CBO concluded, outstanding government debt held by the public will rise to 110 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and then to 185 percent by mid-century, far higher than most any time in the nation’s history. Here, in broad strokes, is what the CBO expects. Federal revenues from all sources will grow in tandem with the economy, taking, on average, slightly over 18 percent of GDP each year. The spending side of the ledger will expand faster. Federal outlays will jump from 23.8 percent of the economy this year to 25.8 percent by the mid-2030s. They will then climb to about 28.9 percent by mid-century, a relative expansion of 5.1 percentage points. According to the CBO, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and lesser entitlements will rise from an estimated 10.8 percent of GDP this year to 13.7 percent in the mid-2030s and 14.9 percent by mid-century. That 4.1 percentage point relative increase amounts to more than four-fifths of the expected relative rise in all spending. The rest of the spending increase will come from the need for Washington to pay interest on an enlarged debt load, itself the result of past increases in entitlements spending. In many respects, the CBO’s forecast is a straightforward extrapolation of past trends. For decades, the outsized growth of entitlements has driven government spending to ever greater portions of the economy. Between 1970 and this year, entitlements rose from 7.6 percent of GDP to 10.8 percent. That growth offset the overall budgetary relief that might have accrued to the drop in defense spending from 7.8 percent of GDP to 3.5 percent. So despite this decline in Pentagon demands, overall federal spending has risen from 18.7 percent of GDP to 23.8. Bleak as the CBO extrapolation of these trends looks, its estimates may be too optimistic. They assume, for example, that defense spending will hold steady at about 3.5 percent of GDP, but in today’s geopolitical climate, defense outlays are more likely to rise relatively. On entitlements, there are also signs of budgetary optimism. Three considerations offer perspective. President Joe Biden signs the Inflation Reduction Act as Democrat lawmakers look on at the White House in Washington on Aug. 16, 2022. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images) First, the CBO made its projections before President Joe Biden ordered student debt relief or signed two large spending bills—the CHIPS for America Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Although the White House insists that these two pieces of legislation will more than pay for themselves, independent analyses, including that of the CBO, indicate that Washington will likely increase spending and otherwise enlarge deficits. Second, the government has already decided to continue the subsidies under the Affordable Care Act, even though they were set to expire. Especially given how aspects of the IRA suggest enlarged subsidies along these lines, spending in this area will likely accumulate over time to enlarge the portion of the budget and the GDP absorbed by entitlements. Third, and most significant, is the likely impact of aging on the country’s population. The baby-boom generation is retiring and will vastly increase the population of dependent retirees. In 1970, for example, some 10 percent of the population was 65 years old or older. By 2019, that figure had grown to 16 percent. The Census Bureau estimates that by the mid-2030s, that figure will rise to 21 percent and 22 percent by mid-century. This huge proportion of older people cannot help but increase demands for Social Security, Medicare, and other federal entitlements. CBO estimates try to account for this trend but likely insufficiently. None of this is to say that entitlements—already at some two-thirds or more of the federal budget–are the wrong way for Washington to spend. That is a political decision. Economics can only point out that past and likely future practices condemn federal finances to ever-growing debt burdens until Washington takes one of three admittedly difficult steps: 1) gets control over entitlements, at least enough to moderate their rapid growth rate; 2) accommodates the ever-increasing demand of entitlements by sacrificing other government services, as was done with defense in the past but in today’s geopolitics no longer seems possible; 3) tells the voters that they must pay more in taxes so that their representatives do not have to make these difficult decisions. As the CBO has made clear, albeit indirectly, these are the only ways to avoid a debt burden that many already describe as unsupportable. Views expressed in this article are the opinion

Commentary

Even before the recent spate of spending legislation, the authoritative Congressional Budget Office (CBO) warned of the precarious state of Washington’s finances. Its figures show that the relentless growth in entitlements will push up budget deficits and add to the nation’s already heavy accumulation of public debt.

By 2032, the CBO concluded, outstanding government debt held by the public will rise to 110 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) and then to 185 percent by mid-century, far higher than most any time in the nation’s history.

Here, in broad strokes, is what the CBO expects. Federal revenues from all sources will grow in tandem with the economy, taking, on average, slightly over 18 percent of GDP each year. The spending side of the ledger will expand faster. Federal outlays will jump from 23.8 percent of the economy this year to 25.8 percent by the mid-2030s. They will then climb to about 28.9 percent by mid-century, a relative expansion of 5.1 percentage points.

According to the CBO, Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and lesser entitlements will rise from an estimated 10.8 percent of GDP this year to 13.7 percent in the mid-2030s and 14.9 percent by mid-century. That 4.1 percentage point relative increase amounts to more than four-fifths of the expected relative rise in all spending. The rest of the spending increase will come from the need for Washington to pay interest on an enlarged debt load, itself the result of past increases in entitlements spending.

In many respects, the CBO’s forecast is a straightforward extrapolation of past trends. For decades, the outsized growth of entitlements has driven government spending to ever greater portions of the economy. Between 1970 and this year, entitlements rose from 7.6 percent of GDP to 10.8 percent. That growth offset the overall budgetary relief that might have accrued to the drop in defense spending from 7.8 percent of GDP to 3.5 percent. So despite this decline in Pentagon demands, overall federal spending has risen from 18.7 percent of GDP to 23.8.

Bleak as the CBO extrapolation of these trends looks, its estimates may be too optimistic. They assume, for example, that defense spending will hold steady at about 3.5 percent of GDP, but in today’s geopolitical climate, defense outlays are more likely to rise relatively. On entitlements, there are also signs of budgetary optimism. Three considerations offer perspective.

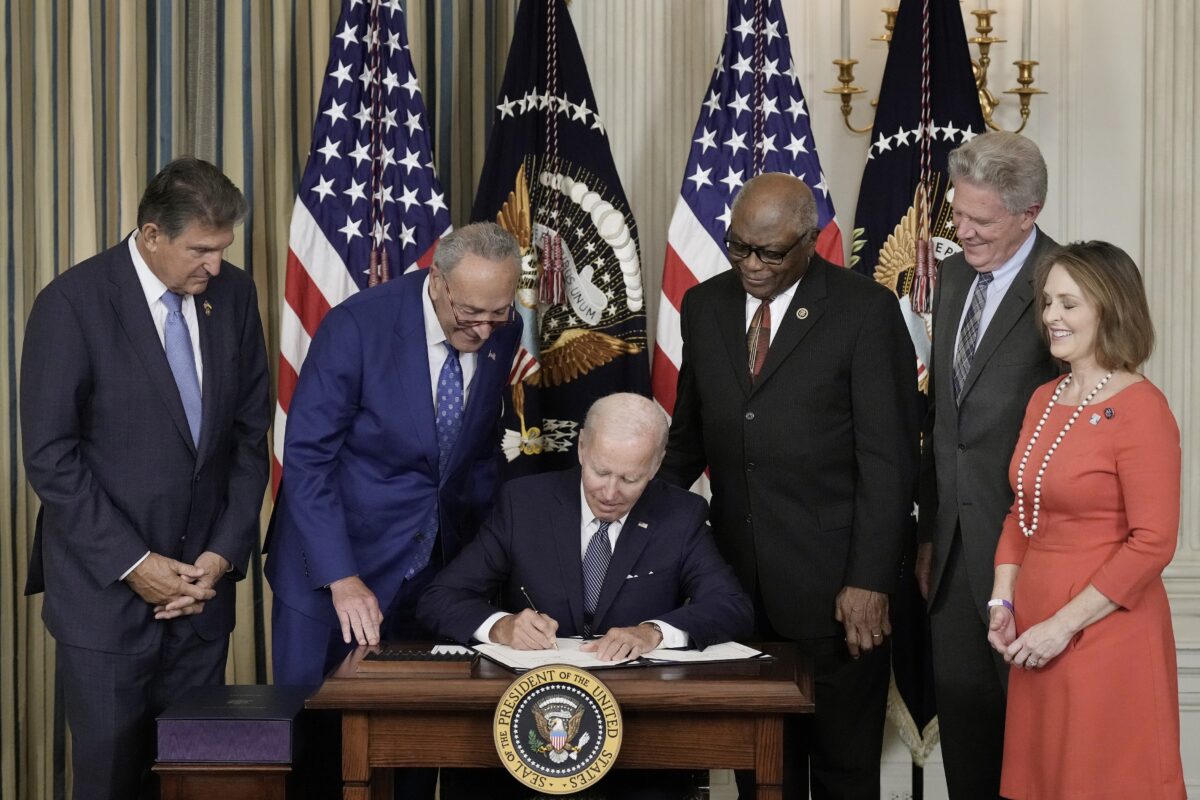

First, the CBO made its projections before President Joe Biden ordered student debt relief or signed two large spending bills—the CHIPS for America Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Although the White House insists that these two pieces of legislation will more than pay for themselves, independent analyses, including that of the CBO, indicate that Washington will likely increase spending and otherwise enlarge deficits.

Second, the government has already decided to continue the subsidies under the Affordable Care Act, even though they were set to expire. Especially given how aspects of the IRA suggest enlarged subsidies along these lines, spending in this area will likely accumulate over time to enlarge the portion of the budget and the GDP absorbed by entitlements.

Third, and most significant, is the likely impact of aging on the country’s population. The baby-boom generation is retiring and will vastly increase the population of dependent retirees. In 1970, for example, some 10 percent of the population was 65 years old or older. By 2019, that figure had grown to 16 percent. The Census Bureau estimates that by the mid-2030s, that figure will rise to 21 percent and 22 percent by mid-century. This huge proportion of older people cannot help but increase demands for Social Security, Medicare, and other federal entitlements. CBO estimates try to account for this trend but likely insufficiently.

None of this is to say that entitlements—already at some two-thirds or more of the federal budget–are the wrong way for Washington to spend. That is a political decision. Economics can only point out that past and likely future practices condemn federal finances to ever-growing debt burdens until Washington takes one of three admittedly difficult steps: 1) gets control over entitlements, at least enough to moderate their rapid growth rate; 2) accommodates the ever-increasing demand of entitlements by sacrificing other government services, as was done with defense in the past but in today’s geopolitics no longer seems possible; 3) tells the voters that they must pay more in taxes so that their representatives do not have to make these difficult decisions. As the CBO has made clear, albeit indirectly, these are the only ways to avoid a debt burden that many already describe as unsupportable.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.