China’s Economy Is Destined to Collapse

CommentaryI have been detailing the problems in the world economy in several of my previous posts. Now, it’s time to explain where it all began and why the situation in the global economy is so precarious. It all starts with China. As I mentioned before, in late 2016 I was baffled. The world had just recovered from a “mini-recession” to which there seemed to be no obvious reason. Suddenly, in 2015, the world economy just started to cave in without any clear indication from the eurozone and the United States that a recession would be coming. Then, in late 2016, the world economy “miraculously” recovered at breakneck speed. I wondered, what an earth was going on? I started digging and stumbled onto the answer when I was analyzing the so-called leading indicators of the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development). A figure presenting time series of the leading indicators of the OECD for China, the eurozone, Germany, and the United States, and China’s leveraging cycle from January 2007 till February 2020. (GnS Economics/OECD/People’s Bank of China) I realized that China—not, for example, the United States—had driven the global economy since the global financial crisis of 2008–09. This was visible from the leading indicators. I (we) estimated that, after 2008, wherever China’s economy was heading, whether in an upturn or a downturn, the economies of both the eurozone and the United States would follow, respectively, with a lag of around two to three months and a lag of around three to four months. I dug deeper and found that China’s economic cycle was totally driven by the leveraging/de-leveraging cycle. This meant that whenever there was a push from Chinese leaders in Beijing to increase lending in the economy (leveraging), economic growth accelerated, and that when Beijing tried to diminish the growth of debt (de-leveraging), economic growth decelerated. Thus, the global economic cycle had become dependent on the opaque decisions of China’s leaders! What happened in 2015/2016, then? In 2015, Chinese leaders tried to stabilize the Chinese economy by tightening the availability of credit (de-leveraging), especially to the manufacturing sector. This led to a slump in the Chinese housing market, which had already weakened in 2014. Because real estate had been the backbone of Chinese economy for the past two decades, the overall economy soured quickly. The Chinese stock market started to fall, and the global economy followed suit. The rapid deterioration of the Chinese economy scared Beijing, and it enacted another round of massive debt stimulus. However, this time around, it did not come from traditional sources. The reason why so few noticed in 2016 that Beijing was running yet another enormous stimulus program was because it was orchestrated through the so-called shadow banking sector. A figure presenting the lending of commercial banks and the size of the balance sheet of un-regulated financial institutions (“shadow banks”) in China. (GnS Economics/People’s Bank of China/National Bureau of Standards) Shadow banking is a term used to describe part of the financial sector that operates outside of, or is only loosely linked to, the traditional system of deposit-taking institutions. It provides credit intermediation through different institutions, instruments, and markets. Effectively, it’s a deposit-like banking system for firms and institutional investors, but because it does not accept deposits in their traditional form from consumers and corporations, it mostly falls outside the banking supervision, regulative framework, and lending statistics. The collapse of the shadow banking sector was the reason behind the financial crisis in 2007–09 (on which more sometime later) and the global recession that followed. However, while the estimated size of the shadow banking sector was around 140 percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States in 2006, it was more than 330 percent of GDP in China in 2016! Alas, China “saved” the world economy from succumbing to a recession in 2016 by issuing an unprecedented credit spree running through the shadow banking sector. It would be truly interesting to know what the current size of the shadow banking sector is in China, but I have been unable to find the current estimates of it from the reports of the People’s Bank of China (PBC). This may be due to the fact that PBC does not publish its estimates anymore or that it publishes them only in Mandarin, or that I have simply missed them regardless of my extensive search. Either way, it does not alter the overall conclusion we made some five years ago: China is an economic giant with “debt clay feet.” Its economy has been kept standing only by relentless and utterly unsustainable debt stimulus since 2007. A figure presenting the dollar amount of private and government debt and the nominal GDP in dollars in China, from 1995 till 2017. (GnS Economics/Mbaye/Badia and Chae (2018)/NBS) A

Commentary

I have been detailing the problems in the world economy in several of my previous posts. Now, it’s time to explain where it all began and why the situation in the global economy is so precarious. It all starts with China.

As I mentioned before, in late 2016 I was baffled. The world had just recovered from a “mini-recession” to which there seemed to be no obvious reason. Suddenly, in 2015, the world economy just started to cave in without any clear indication from the eurozone and the United States that a recession would be coming. Then, in late 2016, the world economy “miraculously” recovered at breakneck speed. I wondered, what an earth was going on?

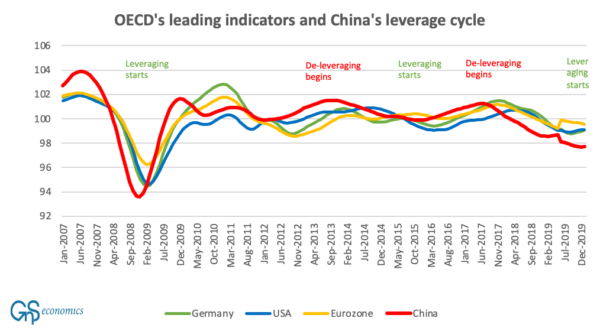

I started digging and stumbled onto the answer when I was analyzing the so-called leading indicators of the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development).

I realized that China—not, for example, the United States—had driven the global economy since the global financial crisis of 2008–09. This was visible from the leading indicators. I (we) estimated that, after 2008, wherever China’s economy was heading, whether in an upturn or a downturn, the economies of both the eurozone and the United States would follow, respectively, with a lag of around two to three months and a lag of around three to four months.

I dug deeper and found that China’s economic cycle was totally driven by the leveraging/de-leveraging cycle. This meant that whenever there was a push from Chinese leaders in Beijing to increase lending in the economy (leveraging), economic growth accelerated, and that when Beijing tried to diminish the growth of debt (de-leveraging), economic growth decelerated. Thus, the global economic cycle had become dependent on the opaque decisions of China’s leaders!

What happened in 2015/2016, then?

In 2015, Chinese leaders tried to stabilize the Chinese economy by tightening the availability of credit (de-leveraging), especially to the manufacturing sector. This led to a slump in the Chinese housing market, which had already weakened in 2014. Because real estate had been the backbone of Chinese economy for the past two decades, the overall economy soured quickly. The Chinese stock market started to fall, and the global economy followed suit.

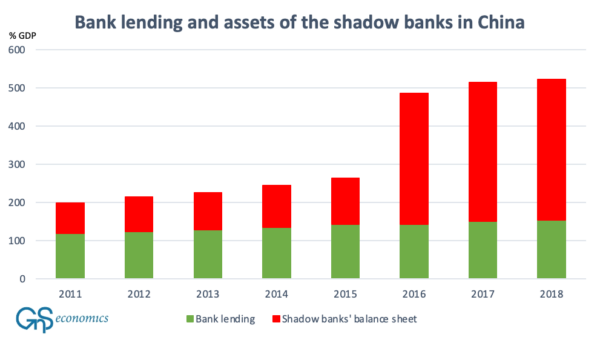

The rapid deterioration of the Chinese economy scared Beijing, and it enacted another round of massive debt stimulus. However, this time around, it did not come from traditional sources. The reason why so few noticed in 2016 that Beijing was running yet another enormous stimulus program was because it was orchestrated through the so-called shadow banking sector.

Shadow banking is a term used to describe part of the financial sector that operates outside of, or is only loosely linked to, the traditional system of deposit-taking institutions. It provides credit intermediation through different institutions, instruments, and markets. Effectively, it’s a deposit-like banking system for firms and institutional investors, but because it does not accept deposits in their traditional form from consumers and corporations, it mostly falls outside the banking supervision, regulative framework, and lending statistics.

The collapse of the shadow banking sector was the reason behind the financial crisis in 2007–09 (on which more sometime later) and the global recession that followed. However, while the estimated size of the shadow banking sector was around 140 percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States in 2006, it was more than 330 percent of GDP in China in 2016!

Alas, China “saved” the world economy from succumbing to a recession in 2016 by issuing an unprecedented credit spree running through the shadow banking sector.

It would be truly interesting to know what the current size of the shadow banking sector is in China, but I have been unable to find the current estimates of it from the reports of the People’s Bank of China (PBC). This may be due to the fact that PBC does not publish its estimates anymore or that it publishes them only in Mandarin, or that I have simply missed them regardless of my extensive search.

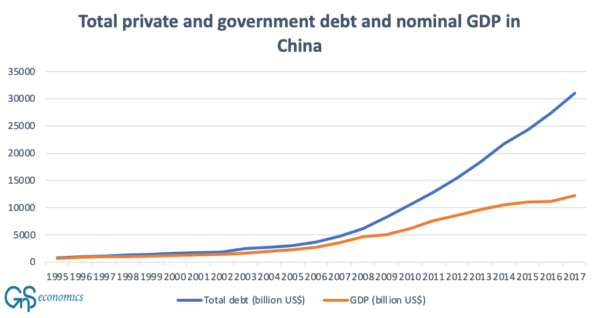

Either way, it does not alter the overall conclusion we made some five years ago: China is an economic giant with “debt clay feet.” Its economy has been kept standing only by relentless and utterly unsustainable debt stimulus since 2007.

Alas, China’s economy is heading into a nearly inevitable collapse.

It is obvious that the economic collapse of China would bring serious social unrest and even lead to an outright uprising. I consider this as the primary reason of the tightening grip of China’s Communist Party on Chinese citizens. It wants to make sure that when the economy implodes, it has the means to quell the massive discontent it will give a rise to.

For the world economy, this is not good news, as we have effectively made ourselves into an economic hostage of two totalitarian regimes, Russia and China. It should be noted that this has been our own doing. Our politicians have not listened to the voices warning us of the increasing economic dependence on China and Russia.

Now, we are learning that lesson the hard way. Let’s just hope this time the warning gets through to those who should listen.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.