China Continues Stealing US Tech

CommentaryPresident Joe Biden seems unwilling to help American trade and investment interests, at least as far as China is concerned. U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Catherine Tai has demanded that Beijing live up to the promises it made in the Phase 1 trade agreement with the Trump administration. But at the same time, she has promised not to “escalate,” signaling that little would happen if Beijing failed to keep those promises. Especially on the issue of China’s decades-long drive to acquire American technology and intellectual property, there is little reason to look for relief. Beijing’s primary way to grab the fruits of American innovation comes through its insistence that any U.S. firm operating in China will have a Chinese partner to which it must transfer its trade secrets and technology. Though not strictly illegal, Beijing’s insistence does fly in the face of international norms. But this is not China’s only way to acquire technologies and business secrets. Frequently, Chinese firms buy high-tech American equipment and, despite patent protections, reproduce it for use in China and elsewhere. American firms continually complain about seeing their designs under Chinese labels even in U.S. markets. Cyber theft is common. News emerges regularly about cyber attacks organized and conducted from Beijing. The list of firms hit by such menacing behavior is a long one and includes Google, Northrup Grumman, Dow Chemical, IBM, Hewlett Packard, and the AFL-CIO, among others, and through them, their associates and clients, including the federal bureaucracy. Beijing’s “Thousand Talents Plan” uses cash incentives to induce people to turn over pieces of intellectual property belonging to their employers, sometimes even when these people are working on U.S. government grants, as in the famous case in which Harvard Professor Charles Lieber was convicted of just such theft. Harvard University nanotechnology professor Charles Lieber (R) arrives at the federal courthouse in Boston, Mass., on Dec. 14, 2021. (Brian Snyder/Reuters) According to FBI Director Christopher Wray, some 80 percent of all economic espionage prosecutions involve China. He has stated that his bureau has more than 2000 open cases of Chinese espionage and opens a new case every 12 hours. “There is,” he said, “just no country that presents a broader threat to our ideas, our innovation, and our economic security than China.” Putting a figure on the damage to which Director Wray alludes, Michael Orlando, acting director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center (NCSC), estimates that China’s theft of technology and other intellectual property costs American businesses a minimum of $200 billion a year. That is just the market value of what is stolen. When including the sales losses involved, the Center’s estimate rises to $600 billion a year. Every president for almost 40 years has tried to get Beijing to change its ways, all to no avail. The failure of each has forced his successor to try in a different way. Reagan began the process in 1986. It did so little good that Bill Clinton had to revisit the matter some years later, and his lack of success working through the World Trade Organization (WTO) forced George W. Bush to look at the matter in 2006. Because Bush got nowhere, Barack Obama had to press the issue in 2015, and his failure to stop Chinese patent violations and the theft of intellectual property (IP) generally, led Trump to impose a broad array of tariffs on Chinese imports. That more extreme action seemed to make progress. Beijing in January 2020 promised among other things to streamline procedures for Americans to protect their patent rights from Chinese infringements. Soon after Biden took office, however, it became clear that Trump’s effort, too, had failed. Director Wray’s remarks make that clear. But unlike his predecessors, Biden seems unwilling to even try to remedy the situation. No new initiatives have emerged. On the contrary, Biden seems determined to ease pressure on Beijing. The Department of Justice (DOJ) recently decided to close its special “China initiative,” which focused on Chinese espionage and cyber threats. The White House has also floated the idea of lifting tariffs on Chinese goods. The government wants to do this not to help China but rather to ease inflationary pressures. Nonetheless, such a step would remove any pressure from Beijing to live up to its promises. When a Chinese court recently declared that no Chinese firm could be sued for the theft of technology anywhere in the world, the White House did not even comment on this clear defiance of international norms and clear threat to American business interests. After so much failure on this matter, it was never realistic to expect much from any new administration. But it is not unreasonable to expect the White House to at least try to remedy what is clearly a burden on American business that amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars a

Commentary

President Joe Biden seems unwilling to help American trade and investment interests, at least as far as China is concerned. U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Catherine Tai has demanded that Beijing live up to the promises it made in the Phase 1 trade agreement with the Trump administration. But at the same time, she has promised not to “escalate,” signaling that little would happen if Beijing failed to keep those promises. Especially on the issue of China’s decades-long drive to acquire American technology and intellectual property, there is little reason to look for relief.

Beijing’s primary way to grab the fruits of American innovation comes through its insistence that any U.S. firm operating in China will have a Chinese partner to which it must transfer its trade secrets and technology. Though not strictly illegal, Beijing’s insistence does fly in the face of international norms. But this is not China’s only way to acquire technologies and business secrets.

Frequently, Chinese firms buy high-tech American equipment and, despite patent protections, reproduce it for use in China and elsewhere. American firms continually complain about seeing their designs under Chinese labels even in U.S. markets.

Cyber theft is common. News emerges regularly about cyber attacks organized and conducted from Beijing. The list of firms hit by such menacing behavior is a long one and includes Google, Northrup Grumman, Dow Chemical, IBM, Hewlett Packard, and the AFL-CIO, among others, and through them, their associates and clients, including the federal bureaucracy.

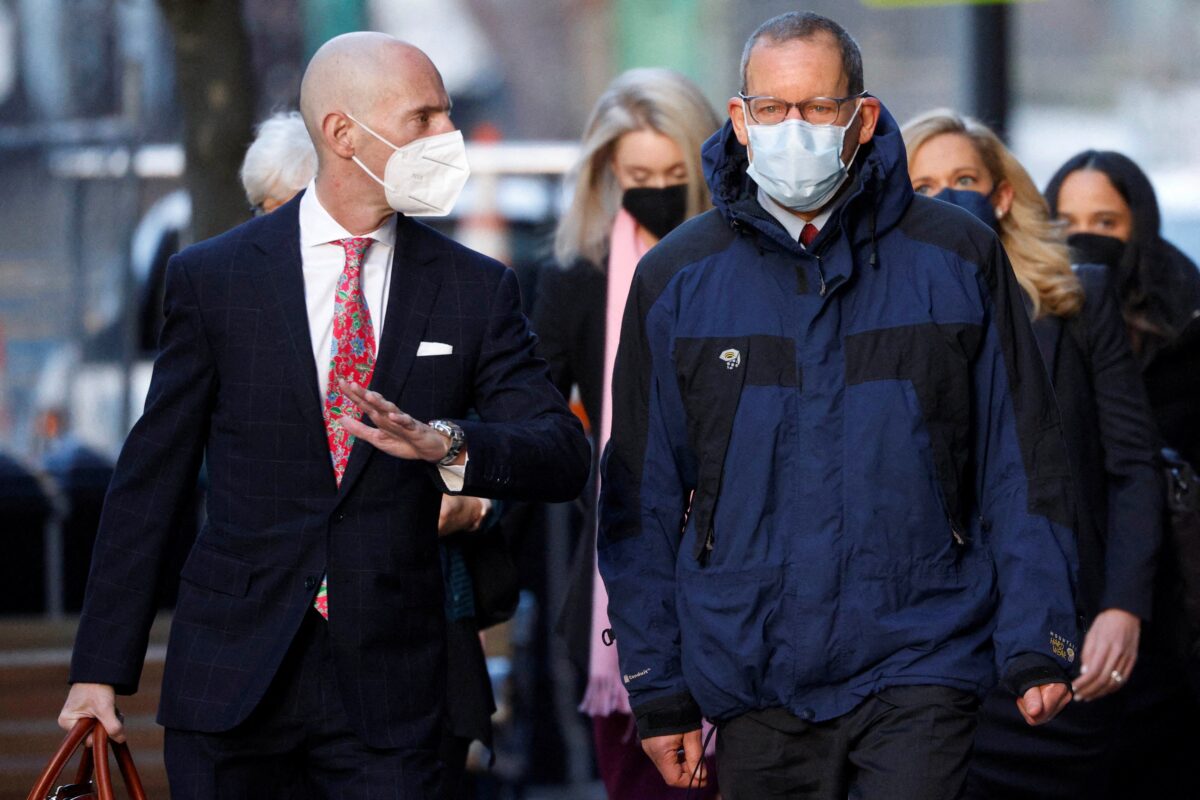

Beijing’s “Thousand Talents Plan” uses cash incentives to induce people to turn over pieces of intellectual property belonging to their employers, sometimes even when these people are working on U.S. government grants, as in the famous case in which Harvard Professor Charles Lieber was convicted of just such theft.

According to FBI Director Christopher Wray, some 80 percent of all economic espionage prosecutions involve China. He has stated that his bureau has more than 2000 open cases of Chinese espionage and opens a new case every 12 hours. “There is,” he said, “just no country that presents a broader threat to our ideas, our innovation, and our economic security than China.”

Putting a figure on the damage to which Director Wray alludes, Michael Orlando, acting director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center (NCSC), estimates that China’s theft of technology and other intellectual property costs American businesses a minimum of $200 billion a year. That is just the market value of what is stolen. When including the sales losses involved, the Center’s estimate rises to $600 billion a year.

Every president for almost 40 years has tried to get Beijing to change its ways, all to no avail. The failure of each has forced his successor to try in a different way. Reagan began the process in 1986. It did so little good that Bill Clinton had to revisit the matter some years later, and his lack of success working through the World Trade Organization (WTO) forced George W. Bush to look at the matter in 2006. Because Bush got nowhere, Barack Obama had to press the issue in 2015, and his failure to stop Chinese patent violations and the theft of intellectual property (IP) generally, led Trump to impose a broad array of tariffs on Chinese imports. That more extreme action seemed to make progress. Beijing in January 2020 promised among other things to streamline procedures for Americans to protect their patent rights from Chinese infringements.

Soon after Biden took office, however, it became clear that Trump’s effort, too, had failed. Director Wray’s remarks make that clear. But unlike his predecessors, Biden seems unwilling to even try to remedy the situation. No new initiatives have emerged. On the contrary, Biden seems determined to ease pressure on Beijing. The Department of Justice (DOJ) recently decided to close its special “China initiative,” which focused on Chinese espionage and cyber threats. The White House has also floated the idea of lifting tariffs on Chinese goods. The government wants to do this not to help China but rather to ease inflationary pressures. Nonetheless, such a step would remove any pressure from Beijing to live up to its promises. When a Chinese court recently declared that no Chinese firm could be sued for the theft of technology anywhere in the world, the White House did not even comment on this clear defiance of international norms and clear threat to American business interests.

After so much failure on this matter, it was never realistic to expect much from any new administration. But it is not unreasonable to expect the White House to at least try to remedy what is clearly a burden on American business that amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.