Can Wisdom Be Restored in the ‘Little Pinkies’ Era?

New education in Hong Kong: learn civil responsibility, not civil rights, to develop little pinkies (young pro-CCP Chinese).Commentary More than 300 school principals and representatives of the school sponsoring bodies and educational organizations attended the Patriotic Education Summit Forum opening ceremony and the Patriotic Education Centre run by the Hong Kong Federation of Education Workers on July 16. The first two guests mentioned in Chief Executive John Lee Ka-Chiu’s speech, were Yang Yirui, Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hong Kong, and Jiang Jianxiang, Minister of Education, Science and Technology of the Liaison Office. We cannot help but ask: Will the high-profile involvement of the Liaison Office affect the image of “one country, two systems” when education is a matter of autonomy for Hong Kong? This question is no longer relevant in the “New Hong Kong” era. As early as the 1980s, Liaison Office (then New China News Agency) officials had openly emphasized that education is “a land contested by all strategists (bingjia bizheng zhi di).” Hong Kong is no longer what it was a decade ago, and Beijing’s “all-encompassing power of control and government (quanmian guanzhiquan)” has taken precedence over everything else. A boy with a banner “anti-brainwashing” during the protest on Aug. 29, 2012. (Sung Pi-Lung/The Epoch Times) A decade ago, in 2012, national education was in an uproar. The government ordered the establishment of an independent Moral and National Education curriculum. A Chinese Model teacher reference was published by the government-sponsored National Education Services Center containing obvious bias, such as calling the Chinese communist regime “progressive, selfless and united” and American politics “a dreadful struggle between political parties and a disaster for the people.” All these caused a public outcry. Groups such as Scholarism and Parents’ Concern Group on National Education protested throughout the summer, staging marches, occupying the government headquarters, striking classes, and going on hunger strike. On the evening of Sept. 7, 2012, 120,000 people gathered at the government headquarters. Finally, the government gave in and announced the next day that there would be no timetable for implementing national education and that schools could decide on their own whether to offer national education. After ten years, given the fall of civil society and total silence under the National Security Law today, John Lee can say at ease in his speech that the government will “correct the wrong values of the youth, tell positive stories of China, tell positive stories of Hong Kong, sternly and solemnly in all righteousness.” Such “righteousness” has already been manifested explicitly in some new Citizenship and Social Development textbooks: Hong Kong was never a colony, students will learn only civil responsibilities but not civil rights, and China does not have many problems as commonly believed. If students take it all in, a new generation of naïve “Little Pinkies” (young pro-CCP Chinese) will be on the horizon. Civic education of this kind is a great leap backward. I have a copy of the “New Citizenship in High School” textbook published in China during the “Kuomintang’s reactionary rule” (1930s). It has chapters on population, agriculture, workers’ life, job market, and marriage; in other words, it discusses rather than avoids problems of China. It also discusses both democracy and dictatorship when talking about politics. Although it obviously sings the Kuomintang’s national government’s praises, it does not shy away from basic political concepts. ‘Telling positive’ (shuohao) is not an educational concept but political propaganda. Education in Hong Kong has always emphasized “constructing knowledge,” not “telling positive.” Paying undue emphasis on telling positive stories is like saying, “look, I am not objective, I am here to wash your brain.” In the new era of national security, where we are all required to learn “important speeches” of the “people’s leader,” party stereotypes will create a one-voice learning environment without critical thinking amidst the positive stories as told in Hong Kong’s primary and secondary schools. Will we only have “Little Pinkies” in the next generation? Optimistically, there may be some Liang Qichao as well. A pioneer of the reform movement in the late Qing dynasty, Liang was originally a high achiever in eight-legged essays, having won the juren degree in the provincial level of imperial examination at the age of 16. It was only when he met Kang Youwei, a master of both Confucian classics and new Western learning, whose knowledge was like “the sound of the tide of the sea and the roar of a lion,” that Liang finally realized that what he had been complacent about was only “hundreds of years of useless old learning.” Then he resigned from the Xuehai Tang, an elitist traditional school, and enrolled in Kang’s Hall

New education in Hong Kong: learn civil responsibility, not civil rights, to develop little pinkies (young pro-CCP Chinese).

Commentary

More than 300 school principals and representatives of the school sponsoring bodies and educational organizations attended the Patriotic Education Summit Forum opening ceremony and the Patriotic Education Centre run by the Hong Kong Federation of Education Workers on July 16.

The first two guests mentioned in Chief Executive John Lee Ka-Chiu’s speech, were Yang Yirui, Commissioner of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hong Kong, and Jiang Jianxiang, Minister of Education, Science and Technology of the Liaison Office.

We cannot help but ask: Will the high-profile involvement of the Liaison Office affect the image of “one country, two systems” when education is a matter of autonomy for Hong Kong?

This question is no longer relevant in the “New Hong Kong” era. As early as the 1980s, Liaison Office (then New China News Agency) officials had openly emphasized that education is “a land contested by all strategists (bingjia bizheng zhi di).”

Hong Kong is no longer what it was a decade ago, and Beijing’s “all-encompassing power of control and government (quanmian guanzhiquan)” has taken precedence over everything else.

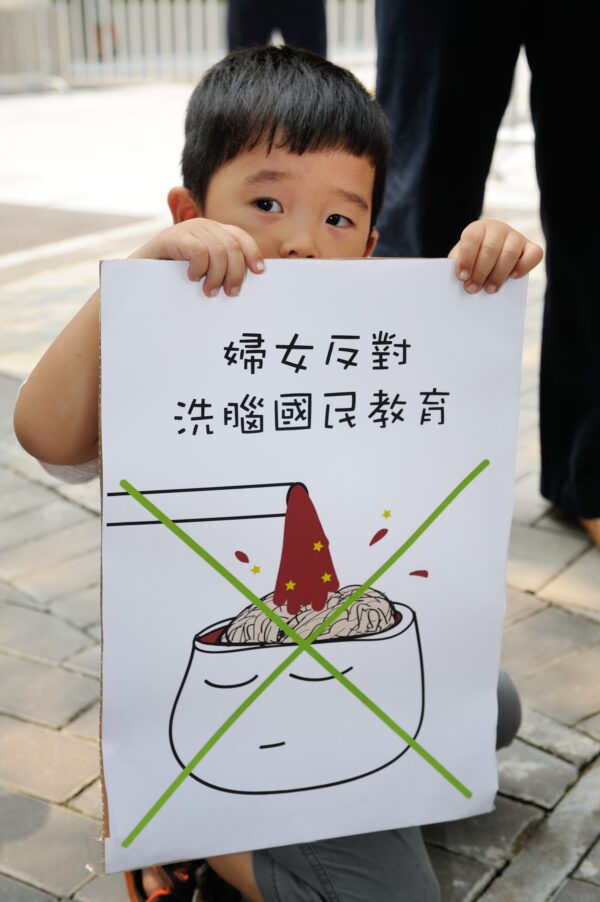

A decade ago, in 2012, national education was in an uproar. The government ordered the establishment of an independent Moral and National Education curriculum. A Chinese Model teacher reference was published by the government-sponsored National Education Services Center containing obvious bias, such as calling the Chinese communist regime “progressive, selfless and united” and American politics “a dreadful struggle between political parties and a disaster for the people.”

All these caused a public outcry. Groups such as Scholarism and Parents’ Concern Group on National Education protested throughout the summer, staging marches, occupying the government headquarters, striking classes, and going on hunger strike.

On the evening of Sept. 7, 2012, 120,000 people gathered at the government headquarters. Finally, the government gave in and announced the next day that there would be no timetable for implementing national education and that schools could decide on their own whether to offer national education.

After ten years, given the fall of civil society and total silence under the National Security Law today, John Lee can say at ease in his speech that the government will “correct the wrong values of the youth, tell positive stories of China, tell positive stories of Hong Kong, sternly and solemnly in all righteousness.”

Such “righteousness” has already been manifested explicitly in some new Citizenship and Social Development textbooks: Hong Kong was never a colony, students will learn only civil responsibilities but not civil rights, and China does not have many problems as commonly believed. If students take it all in, a new generation of naïve “Little Pinkies” (young pro-CCP Chinese) will be on the horizon.

Civic education of this kind is a great leap backward. I have a copy of the “New Citizenship in High School” textbook published in China during the “Kuomintang’s reactionary rule” (1930s). It has chapters on population, agriculture, workers’ life, job market, and marriage; in other words, it discusses rather than avoids problems of China.

It also discusses both democracy and dictatorship when talking about politics. Although it obviously sings the Kuomintang’s national government’s praises, it does not shy away from basic political concepts.

‘Telling positive’ (shuohao) is not an educational concept but political propaganda. Education in Hong Kong has always emphasized “constructing knowledge,” not “telling positive.” Paying undue emphasis on telling positive stories is like saying, “look, I am not objective, I am here to wash your brain.”

In the new era of national security, where we are all required to learn “important speeches” of the “people’s leader,” party stereotypes will create a one-voice learning environment without critical thinking amidst the positive stories as told in Hong Kong’s primary and secondary schools. Will we only have “Little Pinkies” in the next generation?

Optimistically, there may be some Liang Qichao as well. A pioneer of the reform movement in the late Qing dynasty, Liang was originally a high achiever in eight-legged essays, having won the juren degree in the provincial level of imperial examination at the age of 16.

It was only when he met Kang Youwei, a master of both Confucian classics and new Western learning, whose knowledge was like “the sound of the tide of the sea and the roar of a lion,” that Liang finally realized that what he had been complacent about was only “hundreds of years of useless old learning.”

Then he resigned from the Xuehai Tang, an elitist traditional school, and enrolled in Kang’s Hall of Ten Thousand Trees (Wanmu caotang). Liang’s prolific writings brought wisdom and modernity to the Chinese.

I hope that Liangs in the future will restore the people’s wisdom one day.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.