Big Tech Adopts Communist China’s Tactics

This column is adapted from Ken Buck’s book, “Crushed: Big Tech’s War on Free Speech,” available on Jan. 17.Until recently, most Americans probably didn’t think censorship occurred within our borders. They thought it happened in other places—China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and Burma. These repressive countries limit and monitor speech to frightening degrees The American Dream—a phrase the whole world understands—is a dream of freedom, fair play, and financial potential. Is there a similar expression for authoritarian countries? I don’t recall ever hearing anyone pining for the Russian, Chinese, or Saudi Dream. The American Dream is great, it’s exceptional, but unfortunately, it’s in deep peril. The American Dream is threatened—and specifically by Big Tech. Americans rightfully fear that we’re on a path to becoming like Russia, China, or Saudi Arabia if we do nothing. During the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, both Facebook and Twitter actively prevented potentially damaging New York Post reports about Joe Biden’s son Hunter from reaching the public. Reacting to reports about the contents of Hunter Biden’s discarded laptop, including emails that show he introduced his father to a Ukrainian energy executive (something that the elder Biden had denied), Facebook representative Andy Stone said, “We are reducing [the Post’s] distribution on our platform.” Twitter was even more censorious: It blocked users from posting links to the Post’s story and shut down the paper’s Twitter account for two weeks. Interestingly, a year later—after the election was over and Biden was in the Oval Office—Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey admitted that the so-called hacking offense was nonexistent and that silencing the Post was a “mistake.” This was a clear case of Big Tech suppressing information that might have changed the outcome of the 2020 election. They were gatekeepers, selectively determining which stories made it into the marketplace of the news. Similarly, Google’s search engine is an incredible product. But its proprietary algorithmic relevance logic is, by definition, intrinsically exclusionary. Some results appear prominently at the top of the page, while others are buried far below. While the powers that be at Google insist that there’s no political bias in its search engine, one 2018 report found that a news search on the term “Trump” returned an overwhelming number of articles from left-of-center outlets. The first page included two links to CNN, CBS, the Atlantic, CNBC, the New Yorker, and Politico. There were no right-leaning sites listed. The number of instances in which Big Tech uses its monopoly to suppress opinions keeps growing, frequently targeting conservative politicians. Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has found himself locked out of his Facebook page for “repeatedly going against our community standards,” suspended from Twitter for questioning the effectiveness of masks, and had videos removed from YouTube, which is owned by Google. His colleague, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), was temporarily blocked from YouTube for comments about COVID-19 treatments. And Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.) was suspended for two weeks after mocking Time magazine for giving the Woman of the Year award to a “biological male.” If anyone wonders where Big Tech learned the art of censorship, they only need to look at the business relationship between Big Tech and China. In spite of their high-browed statements about basic human rights such as free speech, Big Tech operates in a much different way in China. One of the first times I confronted this type of Big Tech obfuscation was at a Capitol Hill hearing in July 2020 on anti-competitive practices. I was struck by one exchange in particular: the moment Apple’s Tim Cook and Google’s Sundar Pichai couldn’t bring themselves to provide a simple answer to my simple question. Maybe my question wasn’t as simple as I thought. I mentioned that I was planning to introduce a bill requiring American businesses to certify that their supply chains don’t rely on forced labor. Then I said: “While I do not expect you to have intimate knowledge of the legislation, I do want to ask all four of our witnesses a simple yes or no question. Will you certify here today that your company does not use and will never use slave labor to manufacture your products or allow products to be sold on your platform that are manufactured using slave labor?” Cook responded: “I would love to engage on the legislation with you, congressman. But let me be clear, forced labor is abhorrent, and we would not tolerate it in Apple. And so, I would love to get with your office and engage on the legislation.” I had just asked the leader of one of the four biggest companies on the planet for a yes or no answer about using slave labor. He wouldn’t answer. I couldn’t believe it. “Thank you,” I said. “Mr. Pichai?” Pichai responded, “Congressman, I share your concern in this area. I find it abhorrent as well. Happy to e

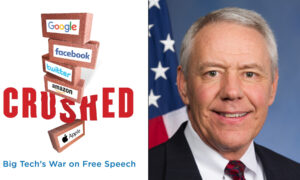

This column is adapted from Ken Buck’s book, “Crushed: Big Tech’s War on Free Speech,” available on Jan. 17.

Until recently, most Americans probably didn’t think censorship occurred within our borders. They thought it happened in other places—China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and Burma. These repressive countries limit and monitor speech to frightening degrees

The American Dream—a phrase the whole world understands—is a dream of freedom, fair play, and financial potential. Is there a similar expression for authoritarian countries? I don’t recall ever hearing anyone pining for the Russian, Chinese, or Saudi Dream.

The American Dream is great, it’s exceptional, but unfortunately, it’s in deep peril. The American Dream is threatened—and specifically by Big Tech. Americans rightfully fear that we’re on a path to becoming like Russia, China, or Saudi Arabia if we do nothing.

During the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, both Facebook and Twitter actively prevented potentially damaging New York Post reports about Joe Biden’s son Hunter from reaching the public. Reacting to reports about the contents of Hunter Biden’s discarded laptop, including emails that show he introduced his father to a Ukrainian energy executive (something that the elder Biden had denied), Facebook representative Andy Stone said, “We are reducing [the Post’s] distribution on our platform.” Twitter was even more censorious: It blocked users from posting links to the Post’s story and shut down the paper’s Twitter account for two weeks.

Interestingly, a year later—after the election was over and Biden was in the Oval Office—Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey admitted that the so-called hacking offense was nonexistent and that silencing the Post was a “mistake.”

This was a clear case of Big Tech suppressing information that might have changed the outcome of the 2020 election. They were gatekeepers, selectively determining which stories made it into the marketplace of the news.

Similarly, Google’s search engine is an incredible product. But its proprietary algorithmic relevance logic is, by definition, intrinsically exclusionary. Some results appear prominently at the top of the page, while others are buried far below. While the powers that be at Google insist that there’s no political bias in its search engine, one 2018 report found that a news search on the term “Trump” returned an overwhelming number of articles from left-of-center outlets. The first page included two links to CNN, CBS, the Atlantic, CNBC, the New Yorker, and Politico. There were no right-leaning sites listed.

The number of instances in which Big Tech uses its monopoly to suppress opinions keeps growing, frequently targeting conservative politicians. Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) has found himself locked out of his Facebook page for “repeatedly going against our community standards,” suspended from Twitter for questioning the effectiveness of masks, and had videos removed from YouTube, which is owned by Google. His colleague, Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), was temporarily blocked from YouTube for comments about COVID-19 treatments. And Rep. Jim Banks (R-Ind.) was suspended for two weeks after mocking Time magazine for giving the Woman of the Year award to a “biological male.”

If anyone wonders where Big Tech learned the art of censorship, they only need to look at the business relationship between Big Tech and China. In spite of their high-browed statements about basic human rights such as free speech, Big Tech operates in a much different way in China.

One of the first times I confronted this type of Big Tech obfuscation was at a Capitol Hill hearing in July 2020 on anti-competitive practices. I was struck by one exchange in particular: the moment Apple’s Tim Cook and Google’s Sundar Pichai couldn’t bring themselves to provide a simple answer to my simple question.

Maybe my question wasn’t as simple as I thought. I mentioned that I was planning to introduce a bill requiring American businesses to certify that their supply chains don’t rely on forced labor. Then I said: “While I do not expect you to have intimate knowledge of the legislation, I do want to ask all four of our witnesses a simple yes or no question. Will you certify here today that your company does not use and will never use slave labor to manufacture your products or allow products to be sold on your platform that are manufactured using slave labor?”

Cook responded: “I would love to engage on the legislation with you, congressman. But let me be clear, forced labor is abhorrent, and we would not tolerate it in Apple. And so, I would love to get with your office and engage on the legislation.”

I had just asked the leader of one of the four biggest companies on the planet for a yes or no answer about using slave labor.

He wouldn’t answer.

I couldn’t believe it.

“Thank you,” I said. “Mr. Pichai?”

Pichai responded, “Congressman, I share your concern in this area. I find it abhorrent as well. Happy to engage with your office and discuss this further.”

Now I was about to get upset. This was a whole new level of obfuscation. Google and Apple wouldn’t disavow slave labor. I decided to give it one more shot.

“I really don’t want to even engage with my office half the time,” I said. “Will you guys agree that slave labor is not something that you will tolerate in manufacturing your products or in products that are sold on your platforms?”

Pichai said, “I agree, Congressman.”

“And Mr. Cook?” I asked.

Cook responded, “We wouldn’t tolerate it. We would terminate a supplier relationship if it were found.”

He still couldn’t follow my request! And he would only agree “if it were found.”

Pathetic.

Why was Cook so cagey about answering the most basic of pledges? Who among us would ever want anything to do with slave labor? Honestly, I thought I was tossing them a softball question—one they could easily answer.

But for Cook, CEO of Apple, slave labor is a tricky issue because the company is so completely enmeshed with China. He was measuring his words—not speaking freely—on a number of China-related issues, including the fact that China is a country that doesn’t allow freedom of speech. No matter what lip service the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) pays to individual freedom, the Party and the State are the only things that matter. And so, the CEO of Apple, a company that sources and builds its products in China, subcontracts out to Chinese firms, and actively sells billions of dollars of its products to China’s 1 billion-plus population, must choose his words carefully.

Especially when it comes to an issue like slave labor.

That’s because Cook undoubtedly knows about the well-documented reports of enforced labor camps in the Xinjiang region, where the CCP has imprisoned an estimated 1 million members of the Muslim Uighur population and even admitted to putting “detainees on production lines for their own good,” according to The New York Times.

Cook and all Apple stockholders should be uneasy. The company’s behavior when it comes to China’s borders has been shameful at times. While its Big Tech brethren Amazon and Google have kowtowed to the CCP, neither can match Apple’s betrayal of democratic ideas at the moment of truth.

That moment came in December 2018, when Apple betrayed students and pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong by bowing to CCP pressure and removing HKmap.live from its app store. HKmap.live allowed users to upload the position of police trying to silence demonstrators, and its presence in the app store detonated a firestorm of criticism from Chinese media, which is monitored by and often serves as the mouthpiece for the CCP.

Justifying the removal of an app that enabled citizens to amass and protest without the threat of water cannons and arrests, Cook issued an email to staffers. He claimed that the decision to pull the app was made after receiving “credible information” from authorities “that the app was being used maliciously to target individual officers for violence and to victimize individuals and property where no police are present.”

He didn’t share that credible information or which “authorities” provided it. The designers of the app took to Twitter to vehemently deny that the app stoked violence and called Apple’s move “clearly a political decision to suppress freedom and human rights.”

As far as I know, no media reports surfaced that confirmed that the app posed a danger to authorities. Meanwhile, isn’t it curious that Apple, a company that constantly talks about protecting individual security, didn’t care about the security of its users in Hong Kong who might have wanted to avoid repressive police actions?

Maybe “curious” is the wrong word. Maybe “hypocritical” is the right one.

In August 2020, Apple released a statement entitled “Our Commitment to Human Rights.” The first heading—I’m not making this up—was “People Come First.”

Here are the opening lines: “Our respect for human rights begins with our commitment to treating everyone with dignity and respect. But it doesn’t end there.

“We believe in the power of technology to empower and connect people around the world—and that business can and should be a force for good. Achieving that takes innovation, hard work, and a focus on serving others.

“It also means leading with our values.”

Yes, let’s talk about Apple’s values, the values of the most highly valued company in the world.

We’ve already seen how Apple’s “values” didn’t stop it from betraying the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong when it removed the HKmap.live app. Those same values were nowhere to be found in 2021 when two apps, the Olive Tree Bible App and the Quran Majeed, were removed from the app store in China because Chinese officials believed that the apps breached Chinese laws on hosting illegal religious texts, according to Apple.

But don’t hold Apple responsible. Oh, no. Here’s how they explain away any responsibility in their human rights document:

“We’re required to comply with local laws, and at times there are complex issues about which we may disagree with governments and other stakeholders on the right path forward.”

That’s certainly true. But nobody required Cook and Apple to manufacture products in one of the most repressive nations in the world, a place controlled by a government that has expressly stated that freedom of the press and freedom of religion pose a threat to the CCP.

If Cook or Apple stockholders have any doubt about the values of the CCP that they, along with so many American companies, willingly enrich, perhaps they could seek out a paper issued in 2013 by the CCP’s General Office with the unwieldy title of “Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere.” Since it was the ninth paper issued that year, most China scholars know it as Document 9.

Calling the state of the world a “complicated, intense struggle,” the paper lays out the CCP’s stance concerning “false ideological trends, positions, and activities.” What follows is an unabashed attack on concepts such as Western constitutional democracy, “universal values,” the promotion of civil society, and freedom of the press. According to the CCP, here’s the big problem with freedom of the press: It can “undermine our country’s principle that the media should be infused with the spirit of the Party.”

The value of the press, per the CCP—Are you listening, Tim Cook?—is that it should be a tool of government control. How’s that for a value?

Document 9 is a frightening mission statement. It explains the relentless flow of human rights abuses in China. Where Tibet doesn’t exist, where you can’t say Taiwan, where you can’t download a Bible or read about the Tiananmen Square massacre. Here’s Document 9’s final call to action:

“We must reinforce our management of all types and levels of propaganda on the cultural front, perfect and carry out related administrative systems, and allow absolutely no opportunity or outlets for incorrect thinking or viewpoints to spread … strengthen guidance of public opinion on the Internet, purify the environment of public opinion on the Internet. Improve and innovate our management strategies and methods to achieve our goals in a legal, scientific, and effective way.”

Some will say that Cook, whose company has tens of billions in sales in China annually, is being fiscally prudent. And this begs a central question of this book: Is it in the consumers’ best interest to allow a monopoly to control the marketplace and speech? The commercial marketplace and the marketplace of ideas operate in the best interests of consumers when there’s the freedom to choose.

This is the line that has surfaced time and again as I researched this book. Story after story cast a shadow over these companies—companies that, let’s be honest, are terrific, innovative entities that have made a lot of people rich and improved the lives of employees and customers. But for all the good they do, their quest for market control involves self-preferencing, market manipulation, and anticompetitive business practices. Open up the ideological engines of these companies, and it’s like there’s a vacuum sucking out any sense of balance, propriety, fairness, and decency. That’s the curse of monopoly power. It just wants to feed itself. There are no checks and balances within the market because the market has been locked up.

Apple isn’t the only Big Tech company playing fast and loose with the levers of democracy. How about the hypocrisy of Operation Dragonfly—Google’s secret program to launch a censored version of its search engine in China.

That’s right: The company that once used the slogan “don’t be evil” cut a deal to bring its best-of-breed search engine to China and block every single thing that the CCP finds objectionable. The terms of Dragonfly called for Google’s search to sync with all the banned subjects and content excluded by the Great Firewall of China—the government-administered buffer to the Western world.

That meant that information about basic human rights, freedom of the press, democracy, criticism of China’s policies or leaders, or any mention of the Tiananmen Square massacre, wouldn’t show up in Dragonfly’s searches. Information deemed problematic or unacceptable would be suppressed, airbrushed, and whited out for users in China.

Even more problematic was the idea that Google, which tracks and monitors data fanatically, would be able to monitor and identify users who searched for terms banned by the CCP. Activists and human rights experts worried that the search engine would operate as a targeting tool for China’s Big Brother-like surveillance state.

Dragonfly went beyond the planning stages. According to The Intercept, the liberal site that broke the story, development on the project accelerated after Google’s CEO, Pichai, met with a top Chinese government official in 2017. A cadre of Google coders produced apps with names such as “Maotai” and “Longfei” to demonstrate the censored, China-compliant version of Google.

Fortunately, The Intercept story about Dragonfly—and the obvious concerns about America’s top data company buddying up with the world’s No. 1 surveillance state—didn’t sit well. A year later, in 2019, Google executive Karan Bhatia delivered some welcome news to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee: “We have terminated Project Dragonfly.”

It’s interesting to know that while Google cooperated with the CCP, it refused to renew a contract with the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) to work on the Pentagon’s Project Maven, which uses artificial intelligence to interpret video images. Apparently, pacifist programmers at the search company were worried that their work might be used for advanced weapons or drone strikes, and so 4,000 workers signed petitions demanding “a clear policy stating that neither Google nor its contractors will ever build warfare technology.”

Judging by the silence of programmers over Dragonfly and the upheaval over Maven, it seems like employees there have things backward: “Chinese censorship good, U.S. military security bad.”

But maybe that attitude makes sense. China is a surveillance state that gathers data on its citizens to maintain control over them. Google does something very similar—it gathers massive amounts of data on citizens to sell them a click to a car, a candidate, or whatever else someone is hawking.

Like Apple, Google has a human rights document. Here’s the beginning of the second paragraph: “In everything we do, including launching new products and expanding our operations around the globe, we are guided by internationally recognized human rights standards.”

How could the company say it believes in these ideas and then go build a restrictive search engine for China? It didn’t hold those values until The Intercept blew the whistle and the company looked ridiculously bad. It valued the DOD until its engineers all threatened to quit. It values openness and making all data free to crawl, index, and share, but if individuals want to take the data Google has collected and give it to another search engine or ad exchange? Er, that’s a little problematic.

Let’s be honest: The most important value of Apple and Google and all these companies is the value of their stock price. The driver here is making sure that there isn’t a competitor that challenges the price structure for their products. This means that it’s more important than ever for these companies to control the marketplace of ideas—monopolizing a market means that you can control the ideas that go into the market. And, therefore, you can control the perception of your own value. In this way, monopoly power can snowball to ensure even greater power.

It’s a sobering thought to compare Big Tech monopolies, which monitor our digital world and filter news, to China, a totalitarian state with no regard for basic human rights. But the similarities are glaring. With Big Tech monopolies controlling what we see and say, consumers get neither the ability to express themselves freely nor the power to choose different ideas in the market. Ensuring that Americans can exchange information without Big Tech censorship is critical to keeping the marketplace of ideas open.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.