Banished for Their Belief: A Daring Appeal in the Heart of Red China

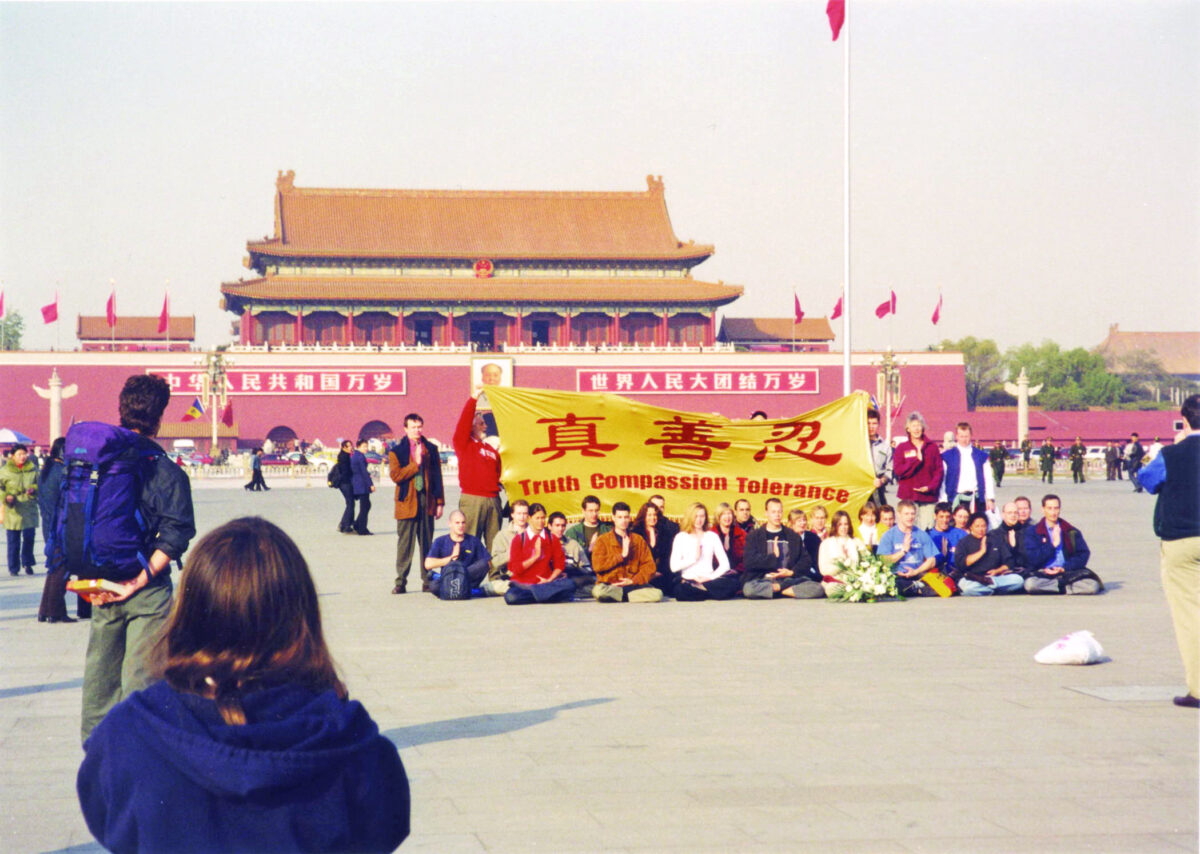

Carrying a large backpack, and clutching a travel guide in one hand, Canadian Joel Chipkar looked the part of a typical tourist. The brown-haired 33-year-old real estate broker, wearing a black jacket and khaki pants, walked briskly to Tiananmen Square, the heart of China’s capital that just over a decade ago had been reddened by the blood of thousands of students slain or wounded by the communist regime’s tanks and guns. The weather on that day—Nov. 20, 2001—was as fine as it got in a city notorious for its dense, grayish smog. The sun was bright, and the air crisp. Pedestrians strolled leisurely in twos and threes over the vast stretches of gray pavement, though Chipkar didn’t notice them much. He was making a bee-line for the north end of the square. He was on a mission. It took no time for Chipkar to find what he was looking for: twenty feet west of the Chinese flag pole, a crowd of two or three dozen people with light hair like him had quietly gathered about, some sitting, others standing and smoothing their collars. The scene was attracting quite a few curious glances. It was still uncommon to see so many Western faces in that country. Chipkar stopped himself while at some distance from the group. He recognized a few faces, but thought it wise not to greet anyone. Drawing any attention to himself could be detrimental to the plan. There was suppressed excitement hanging in the air. In a few moments the group of Westerners would congregate, standing or sitting in four rows as if posing for a group shot in front of the iconic Tiananmen Tower. But this was a ruse; they would later sit down in meditation position, while some would unfurl an eight-foot long golden banner bearing the Chinese characters “truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance”—the three core principles of the persecuted faith group Falun Gong. The police would swarm in, and arrests would follow. And Chipkar’s role was to watch—and document it all. Joel Chipkar (L) seen on the left secretly video taping the appeal of the 36 Westerners on Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China, on Nov. 20, 2001. (Courtesy of Joel Chipkar) The Planning That was two years after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, along with its roughly 70 million to 100 million adherents, its enemy for no apparent reason other than the spiritual practice’s vast popularity. During the 1990s, rows and rows of Falun Gong practitioners could be seen doing the practice’s slow-moving exercises every morning in parks and squares across the country. But this came to a screeching halt in July 1999, when the CCP unleashed a nationwide campaign to eradicate the practice. Adherents had since been the victims of harassment, physical torment, detention, and slave labor. Many were driven out of work or school, and had their books relating to the practice confiscated and burned. Police detain a Falun Gong protester in Tiananmen Square as a crowd watches in Beijing on Oct. 1, 2000 photo. (AP Photo/Chien-min Chung) The persecution had also just reached new heights in 2001. Airwaves and newspapers had capitalized on a self-immolation incident at Tiananmen Square earlier that year—shown later to be staged under Beijing’s order—designed to cast the adherents as suicidal. The intensifying misinformation and hate campaign had sent a steady stream of adherents to Tiananmen Square, a political center and popular tourist spot, to appeal for an end to the suppression. For Falun Gong practitioners anxiously watching outside Chinese borders, the continued plight of their fellow adherents in China told them something more must be done. It took at least a year for the idea of an international appeal to come together. Germany’s Peter Recknagel, a 30-year-old student of Chinese and economics, was among the first to make travel arrangements. When he sensed interests from those in other parts of the world, the plan broadened. Eventually, 36 practitioners from 12 countries across Europe, North America, and Australia would fly to China. Many of them had never met each other before. They kept the instructions to the bare minimum: travel separately; meet up near the flagpole by 2 p.m.; keep a low profile, convey their message of appeal; and stay for however long they could. The organizers took precautions to keep their plans under wraps. To evade possible eavesdropping by the regime, only a few were involved with the organizing, and they talked in Swedish for the most part of the planning. Adam Leining, a 30-year-old musician from America, brought the banner in a suit bag. The night before it all happened, Recknagel and a few others drew down the curtain of the hotel room and turned on loud disco music, then slipped into the room one by one for a little rehearsal. They unfurled the banner to see how big it was and assigned three of their tallest group members to hold it. Falun Gong practitioners from 12 countries pose for a group photo beforing m

Carrying a large backpack, and clutching a travel guide in one hand, Canadian Joel Chipkar looked the part of a typical tourist.

The brown-haired 33-year-old real estate broker, wearing a black jacket and khaki pants, walked briskly to Tiananmen Square, the heart of China’s capital that just over a decade ago had been reddened by the blood of thousands of students slain or wounded by the communist regime’s tanks and guns.

The weather on that day—Nov. 20, 2001—was as fine as it got in a city notorious for its dense, grayish smog. The sun was bright, and the air crisp.

Pedestrians strolled leisurely in twos and threes over the vast stretches of gray pavement, though Chipkar didn’t notice them much. He was making a bee-line for the north end of the square. He was on a mission.

It took no time for Chipkar to find what he was looking for: twenty feet west of the Chinese flag pole, a crowd of two or three dozen people with light hair like him had quietly gathered about, some sitting, others standing and smoothing their collars. The scene was attracting quite a few curious glances. It was still uncommon to see so many Western faces in that country.

Chipkar stopped himself while at some distance from the group. He recognized a few faces, but thought it wise not to greet anyone. Drawing any attention to himself could be detrimental to the plan.

There was suppressed excitement hanging in the air. In a few moments the group of Westerners would congregate, standing or sitting in four rows as if posing for a group shot in front of the iconic Tiananmen Tower. But this was a ruse; they would later sit down in meditation position, while some would unfurl an eight-foot long golden banner bearing the Chinese characters “truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance”—the three core principles of the persecuted faith group Falun Gong.

The police would swarm in, and arrests would follow.

And Chipkar’s role was to watch—and document it all.

The Planning

That was two years after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) declared Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, along with its roughly 70 million to 100 million adherents, its enemy for no apparent reason other than the spiritual practice’s vast popularity. During the 1990s, rows and rows of Falun Gong practitioners could be seen doing the practice’s slow-moving exercises every morning in parks and squares across the country. But this came to a screeching halt in July 1999, when the CCP unleashed a nationwide campaign to eradicate the practice.

Adherents had since been the victims of harassment, physical torment, detention, and slave labor. Many were driven out of work or school, and had their books relating to the practice confiscated and burned.

The persecution had also just reached new heights in 2001. Airwaves and newspapers had capitalized on a self-immolation incident at Tiananmen Square earlier that year—shown later to be staged under Beijing’s order—designed to cast the adherents as suicidal.

The intensifying misinformation and hate campaign had sent a steady stream of adherents to Tiananmen Square, a political center and popular tourist spot, to appeal for an end to the suppression.

For Falun Gong practitioners anxiously watching outside Chinese borders, the continued plight of their fellow adherents in China told them something more must be done.

It took at least a year for the idea of an international appeal to come together. Germany’s Peter Recknagel, a 30-year-old student of Chinese and economics, was among the first to make travel arrangements. When he sensed interests from those in other parts of the world, the plan broadened.

Eventually, 36 practitioners from 12 countries across Europe, North America, and Australia would fly to China. Many of them had never met each other before. They kept the instructions to the bare minimum: travel separately; meet up near the flagpole by 2 p.m.; keep a low profile, convey their message of appeal; and stay for however long they could.

The organizers took precautions to keep their plans under wraps. To evade possible eavesdropping by the regime, only a few were involved with the organizing, and they talked in Swedish for the most part of the planning.

Adam Leining, a 30-year-old musician from America, brought the banner in a suit bag. The night before it all happened, Recknagel and a few others drew down the curtain of the hotel room and turned on loud disco music, then slipped into the room one by one for a little rehearsal. They unfurled the banner to see how big it was and assigned three of their tallest group members to hold it.

When everyone had met up at the Square, two people from Europe were arranged to hold a bouquet of flowers to give off a celebratory feel. That was to buy them time as they got ready.

“There was a signal … then everybody just had to jump into the meditation position,” Recknagel, now 50 and residing in New York state, recalled to The Epoch Times.

“We had to be very, very careful not to blow it up before it happened.”

(Courtesy of Joel Chipkar)

The Witness

Chipkar planned his part as carefully as he could.

He bought a tiny camcorder, a pager-looking device, which he threaded into the strap of his backpack. A hole was cut on the strap so the lens could poke through. Then he spent a good four days looking into the mirror while carrying the backpack to master how to angle the camera. The tape would run for about two hours, and with everything set up, he would be able to walk around with his hands free.

“I thought of everything that could possibly happen or go wrong and I had to plan for that all, because you don’t get a second chance,” Chipkar, now 53 and living in Toronto, said in an interview with The Epoch Times.

The night before the gathering, Chipkar had very poor sleep thinking over every possible small mishap that could jeopardize his mission. The camcorder could malfunction, or the police may arrest him before he reached the site, then all his work would end up in vain.

The Banner Holder

Chipkar’s friend Zenon Dolnyckyi was already among the group when he got there. Ten years his junior, Dolnyckyi had picked up some basic mandarin from some Chinese Falun Gong practitioners back in Toronto.

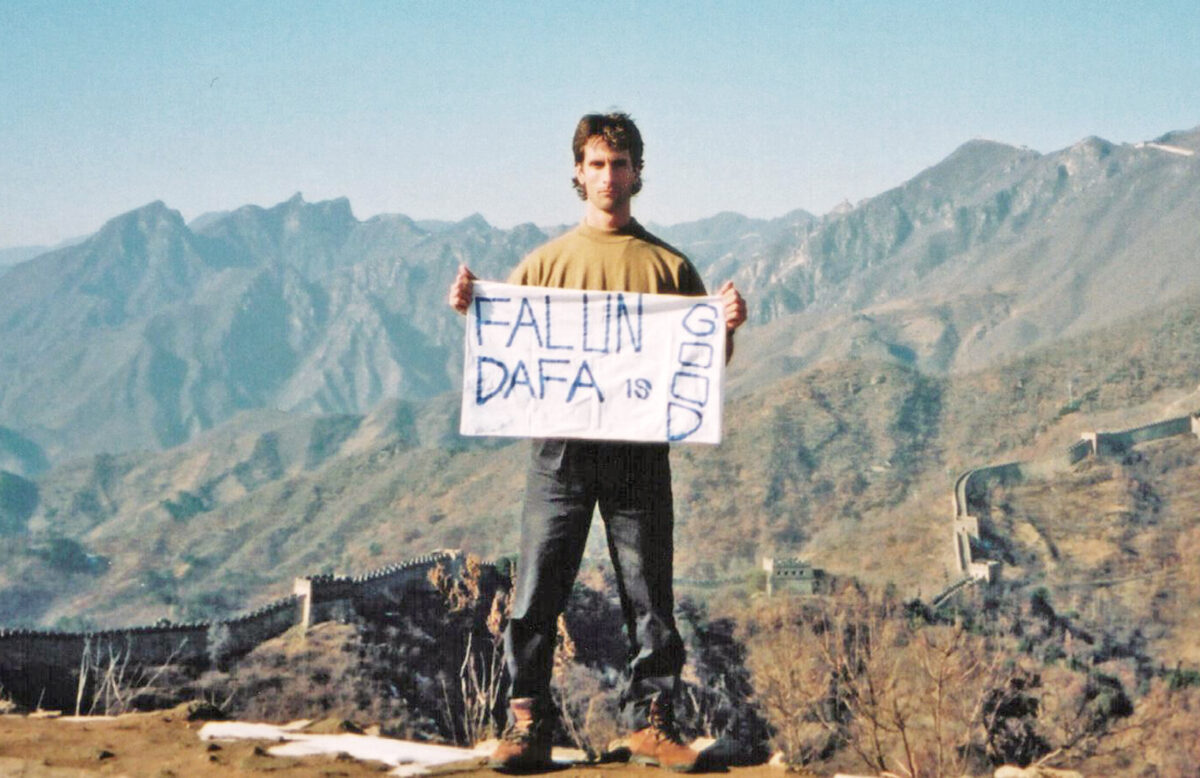

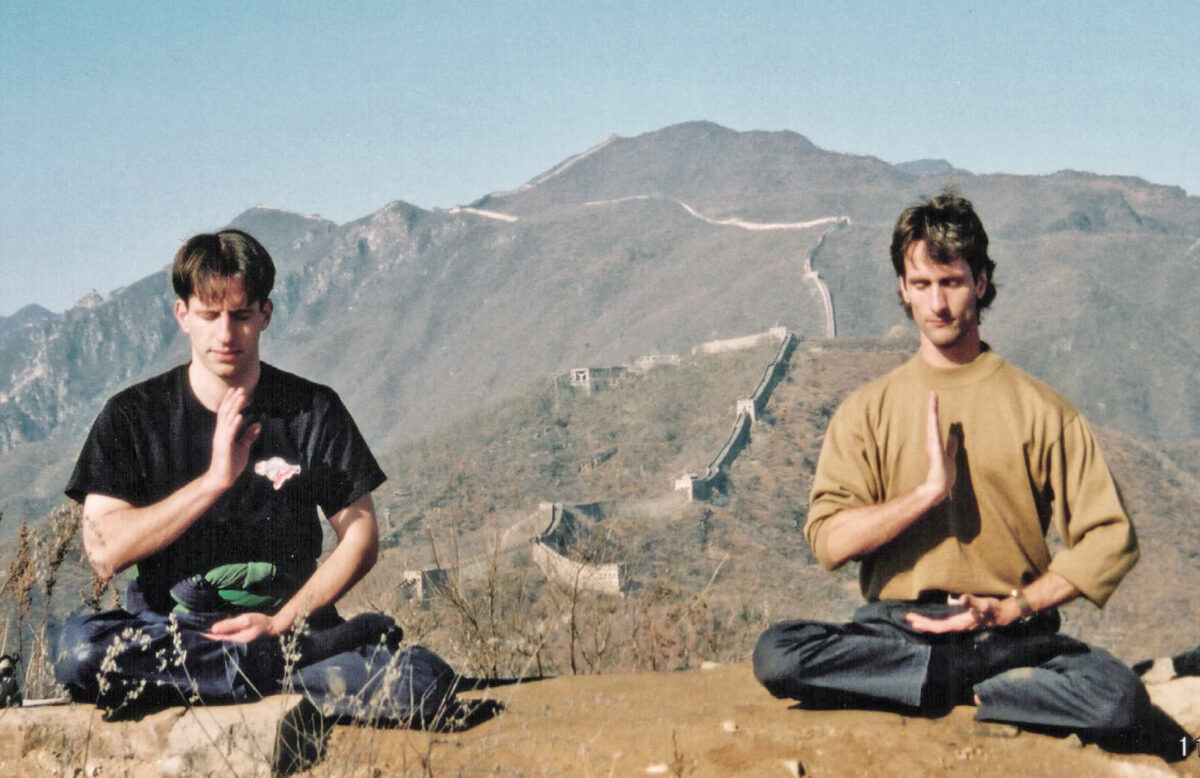

The two had met at the Great Wall a day earlier to hang up a vertical yellow banner that read “Falun Dafa is good.” Dolnyckyi had stayed up at the hotel to paint those Chinese characters onto the banner—a “beautiful, symbolic message,” in Dolnyckyi’s words.

Both had bought return tickets to Canada scheduled for four hours after the Tiananmen gathering.

“See you at the airport,” Dolnyckyi had told Chipkar at the hotel on the morning before the appeal.

But they never did.

Recknagel and Leining were sitting down in a meditation position when the large banner was unfurled. Dolnyckyi stood behind the banner where the character “truthfulness” was, helping to hold it up. “I felt really proud because … they were pushing so strong to hold the banner,” he told The Epoch Times’ affiliate NTD’s “Legends Unfolding” program in 2017.

Within 20 seconds, a car horn pierced the air. Soon, at least six police vans encircled them, uniformed and plainclothes police emerged as if from nowhere, hurling the adherents into the cars while shooing onlookers away.

As the police descended, Dolnyckyi pulled out from his pants leg another yellow makeshift banner he converted from a pillowcase. He had practiced this move in the hotel. While holding this banner, he shouted at the top of his lungs “Falun Dafa is good.”

When the police finally seized him, one of them punched him squarely between his two eyes, causing a bone fracture. More punches then rained on him and he was forced into a white police van, where he found a Swedish man beaten unconscious, and a blond, blue-eyed French woman who the police tried to strangle to prevent her from shouting, “Falun Dafa is good.”

Chipkar, standing at some distance from the pandemonium, watched his friends being hauled away within minutes.

He called a rickshaw back to the hotel and immediately rushed into the bathroom in the hotel lobby, locked the door behind him, and started rewinding the footage. Once he confirmed that it was all there, Chipkar went to the nearest FedEx office and shipped the recordings home.

“I felt really relieved,” Chipkar said. “The way it went in the square when the appeal happened, it was magic—things happened exactly the way they were supposed to.”

The Interrogation

The rest of the group were held at the Tiananmen Square Police Station adjacent to the square, in a windowless cell that had bloodstains on the wall. More violence followed during the interrogations. An Israeli was struck in the face and kicked in the groin.

In a hotel near the airport where they were later transported, a U.S. medical student was hit on the head after he refused to sign and ripped up the police report. One woman was groped by police when she refused to hand over her phone.

Recknagel, who also knows Chinese, warned the police to stop attacking the medical student.

“Do that again, and all the world will know about it,” he recalled telling the officer in mandarin.

The police, in a rage, dragged him to the wall, saying something to the effect of “do you know how it feels to get killed?” Recknagel told The Epoch Times.

The police were nonetheless restrained compared to their handling of local adherents. The group were filmed by police throughout the proceedings, including being supplied food and water, which the adherents suspected was for propaganda purposes. State-run media reports later said the group was treated humanely.

After about 24 to 48 hours, they were sent on a flight and told they could not return to China for five years.

Honoring the Real Heroes

Reflecting two decades later, Chipkar saw nothing heroic in his act.

“It was a moment in time where we did what we thought we had to do,” he said. “We are all trying our best, every one of us.”

Since the start of the persecution, millions of practitioners have been thrown into detention centers, prisons, labor camps, and other facilities, while hundreds and thousands have suffered from torture, according to the Falun Dafa Information Center. An untold number of detained adherents have also been killed for their organs.

Minghui, a U.S.-based website that chronicles the persecution in China, has verified thousands of deaths. Although this is likely only the tip of the iceberg, experts say, owing to the regime’s gargantuan efforts to conceal its brutal campaign.

“The real heroes who deserve the attention are the practitioners on a daily basis in China that go through life and death every time they step out the door,” Chapkar said. “The people who are in China, those are the heroes, not us.”

Recknagel, who spent the first 18 years of his life in East Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall, described his journey to Tiananmen as a “big adventure.”

“Nobody really knew what would come out of that,” he said. There was no telling how much it helped the situation in China, but at least, it was a glimpse into how real and how cruel the persecution in China is.”

“It gives you a kind of kick … to do whatever you can to help to stop it here.”

The moment of the banner unfurling was depicted by artists, fellow adherents, in an oil painting. In the depiction, a translucent golden light effuses from the group of meditators.

“You look at Zhen and Shan and Ren,” he said, referring to the Chinese characters on the banner. “And at that time, we were standing up for that.”

The painting is now on display in a shopping mall exhibition in upstate New York, which Recknagel sometimes visits.

“It’s just nice to have that picture as a memory,” he said.

But for him as well as many others, that memory from two decades ago is inextricably linked to sorrow.

“So many people in China, they stood up for that, and nobody has a picture,” Recknagel said. “Many of them are killed there.”