Avoiding Gluten is Harder Than You Think

Have you tried a “gluten-free” diet and it didn’t work? Maybe it didn’t help you lose weight or reverse your symptoms. Or, perhaps you felt better for a short period of time but then your symptoms returned. If that sounds familiar, it’s possible that gluten is problematic for you, but you made the mistake of trusting the “gluten-free” label—like I did.While an estimated 2 million people in America have celiac disease, roughly 18 million people, or 6 percent of the population, have gluten sensitivity. And since well-meaning medical doctors, health practitioners, and dietitians routinely advise patients with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity to consume certified “gluten-free” foods, that means roughly 20 million Americans rely on that label for their health outcome. That’s a problem because the “gluten-free” label might be making some of them sicker. When I say “gluten,” which foods come to mind? Most people think of foods containing wheat, barley, or rye, such as bread, crackers, and beer. That’s because the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) decides what’s allowed to be labeled as “gluten-free.” According to the FDA, only wheat, barley, and rye contain gluten. However, that definition of gluten is based on outdated information from World War II. In 1944, the Netherlands experienced a “Winter of Starvation” when the Germans cut off their supply of wheat, barley, and rye. At the time, a Dutch pediatrician, Dr. Willem Dicke, was caring for children hospitalized with celiac disease. Dr. Dicke observed that the forced change in the children’s diet resulted in elimination or alleviation of their symptoms, even though the children were starving. After the war ended, those three grains were once again consumed by the children, and they quickly relapsed. While this was the first conclusive evidence that grains trigger celiac disease, it also led to the mistaken “truth” that only wheat, barley, and rye contain gluten. Those three grains were staples in the Netherlands at that time. Therefore, they were naturally characterized as gluten-containing foods. Other grains, such as rice and corn, were not as readily consumed and therefore were not tested to determine if the children’s bodies reacted to those foods. As a result, for roughly 70 years, grains such as rice and corn have been considered “safe” to eat for people with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. And in 2013, this generally recognized “truth” was officially adopted by the FDA when they defined “gluten-free” to be a food that does not contain “wheat, rye, barley, or a crossbred hybrid of these grains.” However, when devising the definition of gluten-containing foods, the FDA simply “assumed” all other grains to be safe, such as corn, rice, quinoa, buckwheat, millet, amaranth, teff, and sorghum. For example, to substantiate their claim that rice and corn are “safe,” the FDA cited evidence that acknowledged that those grains haven’t been adequately studied. In a paper on the topic, research chemist Donald D. Kasarda writes that some people do react to those grains, and the distinction between “safe” grains and unsafe grains was determined “somewhat arbitrarily”: “Rice and corn have generally been considered safe grains for celiac patients, although once again there has been lack of rigorous, controlled, scientific study of these grains in relation to celiac disease, especially with up-to-date methods. … Adverse reactions to what I shall somewhat arbitrarily term safe grains for celiac patients may not be common, but they do exist. Such adverse reactions should be the subject of more research as to the mechanisms involved.” While the FDA largely based its definition of gluten on gliadin, the primary gluten protein found in wheat, today we know there’s not just one gluten protein. There are hundreds of gluten proteins, which means there are probably more that we haven’t discovered. We also know gluten isn’t just in wheat, barley, and rye. Gluten is in all grains, including corn and rice. Each grain contains one or more types of gluten proteins. Below is a table listing some common grains and the primary type of gluten protein they contain (specifically, the prolamine subfraction of gluten). Table 1. The table lists the primary type of prolamine (a subfraction of gluten) in some common grains as well as the percentage of gluten contained in that grain in relation to the total protein content. In some instances, the exact percentages have changed over time because hybrids were designed to contain higher levels of gluten to make fluffier baked goods, but the table provides an estimate of the relative percentages of gluten per grain. The FDA doesn’t acknowledge that gluten exists in all grains. For example, corn surrounds you on all sides in the grocery store. Thanks to farm subsidies, genetically modified, processed corn derivatives are added to the majority of processed foods, from breakfast cereals to cakes to crackers and frozen meals. That

Have you tried a “gluten-free” diet and it didn’t work? Maybe it didn’t help you lose weight or reverse your symptoms. Or, perhaps you felt better for a short period of time but then your symptoms returned. If that sounds familiar, it’s possible that gluten is problematic for you, but you made the mistake of trusting the “gluten-free” label—like I did.

While an estimated 2 million people in America have celiac disease, roughly 18 million people, or 6 percent of the population, have gluten sensitivity. And since well-meaning medical doctors, health practitioners, and dietitians routinely advise patients with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity to consume certified “gluten-free” foods, that means roughly 20 million Americans rely on that label for their health outcome. That’s a problem because the “gluten-free” label might be making some of them sicker.

When I say “gluten,” which foods come to mind?

Most people think of foods containing wheat, barley, or rye, such as bread, crackers, and beer. That’s because the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) decides what’s allowed to be labeled as “gluten-free.” According to the FDA, only wheat, barley, and rye contain gluten. However, that definition of gluten is based on outdated information from World War II.

In 1944, the Netherlands experienced a “Winter of Starvation” when the Germans cut off their supply of wheat, barley, and rye. At the time, a Dutch pediatrician, Dr. Willem Dicke, was caring for children hospitalized with celiac disease. Dr. Dicke observed that the forced change in the children’s diet resulted in elimination or alleviation of their symptoms, even though the children were starving. After the war ended, those three grains were once again consumed by the children, and they quickly relapsed. While this was the first conclusive evidence that grains trigger celiac disease, it also led to the mistaken “truth” that only wheat, barley, and rye contain gluten.

Those three grains were staples in the Netherlands at that time. Therefore, they were naturally characterized as gluten-containing foods. Other grains, such as rice and corn, were not as readily consumed and therefore were not tested to determine if the children’s bodies reacted to those foods. As a result, for roughly 70 years, grains such as rice and corn have been considered “safe” to eat for people with celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. And in 2013, this generally recognized “truth” was officially adopted by the FDA when they defined “gluten-free” to be a food that does not contain “wheat, rye, barley, or a crossbred hybrid of these grains.”

However, when devising the definition of gluten-containing foods, the FDA simply “assumed” all other grains to be safe, such as corn, rice, quinoa, buckwheat, millet, amaranth, teff, and sorghum. For example, to substantiate their claim that rice and corn are “safe,” the FDA cited evidence that acknowledged that those grains haven’t been adequately studied. In a paper on the topic, research chemist Donald D. Kasarda writes that some people do react to those grains, and the distinction between “safe” grains and unsafe grains was determined “somewhat arbitrarily”:

“Rice and corn have generally been considered safe grains for celiac patients, although once again there has been lack of rigorous, controlled, scientific study of these grains in relation to celiac disease, especially with up-to-date methods. … Adverse reactions to what I shall somewhat arbitrarily term safe grains for celiac patients may not be common, but they do exist. Such adverse reactions should be the subject of more research as to the mechanisms involved.”

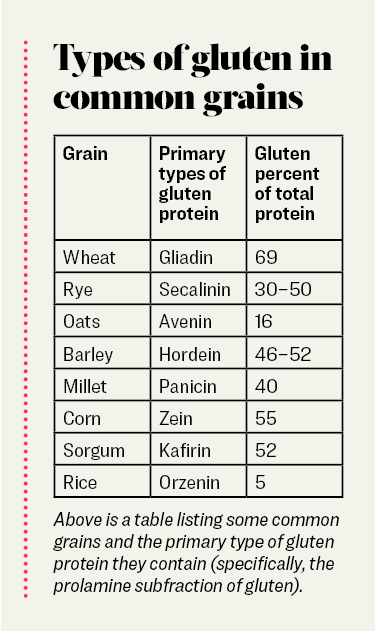

While the FDA largely based its definition of gluten on gliadin, the primary gluten protein found in wheat, today we know there’s not just one gluten protein. There are hundreds of gluten proteins, which means there are probably more that we haven’t discovered. We also know gluten isn’t just in wheat, barley, and rye. Gluten is in all grains, including corn and rice. Each grain contains one or more types of gluten proteins. Below is a table listing some common grains and the primary type of gluten protein they contain (specifically, the prolamine subfraction of gluten).

Table 1. The table lists the primary type of prolamine (a subfraction of gluten) in some common grains as well as the percentage of gluten contained in that grain in relation to the total protein content. In some instances, the exact percentages have changed over time because hybrids were designed to contain higher levels of gluten to make fluffier baked goods, but the table provides an estimate of the relative percentages of gluten per grain.

The FDA doesn’t acknowledge that gluten exists in all grains.

For example, corn surrounds you on all sides in the grocery store. Thanks to farm subsidies, genetically modified, processed corn derivatives are added to the majority of processed foods, from breakfast cereals to cakes to crackers and frozen meals. That means gluten is ubiquitous in the grocery store. Additionally, what are most certified “gluten-free” processed foods made of? Corn or rice.

That’s concerning, because people who react to the gluten in wheat (gliadin) may also react to the entire family of gluten proteins—including the glutens in corn and rice. I did. In 2014, I went “gluten-free” because I was trying to reverse rheumatoid arthritis. Despite adhering to a 100 percent traditional “gluten-free” diet, I couldn’t heal my gastrointestinal tract. I was eating certified “gluten-free” foods thinking I was helping myself heal, but my body reacted to the gluten in corn and rice by mounting an immune response. That protective response created inflammation throughout my body, which contributed to the rapid progression of the autoimmune disease. Once I moved beyond the “gluten-free” label and removed all grains from my diet, I began to heal.

This pattern has also been reported in scientific studies showing that a traditional gluten-free diet (i.e., no wheat, barley, or rye) routinely fails to fully heal the gastrointestinal lining in people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity. For instance, in 2009, an article published in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics concluded that after 16 months on a traditional gluten-free diet, only 8 percent of people healed their gut lining, 65 percent had persistent inflammation, 26 percent had no change, and 1 percent got worse. The authors concluded, “Complete normalization of duodenal lesions is exceptionally rare in adult coeliac patients despite adherence to GFD [a traditional gluten-free diet].”

In other words, a traditional “gluten-free” diet failed to help 92 percent of people.

Furthermore, a study published in 2013 in BMC Gastroenterology focused on patients who had previously followed a traditional “gluten-free” diet with no relief from symptoms. After following a diet of exclusively whole, unprocessed foods—including no “gluten-free” processed foods, 82 percent of patients reported elimination of symptoms, including resolution of prior celiac enteropathy.

The truth is, we have known since the late 1970s that gluten in corn can affect people with celiac disease and irritable bowel disease. A study published in Clinical Experimental Immunology in 1979 reported that people with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and celiac disease had elevated antibodies when they ate corn. The authors concluded that the increase in antibodies suggested, “increased mucosal permeability,” which is another name for leaky gut. Similar findings of an inflammatory response following corn exposure were published in 1991, 2005, and 2012.

To be clear, there’s a lot we still don’t know about gluten. For example, do people with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity always react to the glutens contained in corn and rice? Not necessarily. In 2005, a study published in Gut reported that nearly 50 percent of subjects developed gastrointestinal inflammation and antibodies to corn—however, we don’t know the exact number.

The bottom line is this: The current “gluten-free” label doesn’t support a true gluten-free lifestyle, which removes all forms of gluten. It adds to the confusion because the label supports the traditional gluten-free diet (no wheat, barley, or rye).

The “gluten-free” labeling confusion is one reason why some people don’t experience improvements when they go “gluten-free.” If they removed wheat, barley, and rye, but their symptoms didn’t improve, it’s possible they were still reacting to the glutens in other grains. In addition, some people experience gluten-free whiplash, which occurs when the traditional forms of gluten are removed and initially there is improvement. However, a short time later, symptoms return. Gluten-free whiplash is proof that all grains contain gluten.

But there’s good news. As awareness increases, some scientists are questioning whether corn and rice are safe for celiac and gluten-sensitive populations, which may lead to a revised definition of “gluten-free.” For now, our grocery stores are filled with corn and rice. “Gluten-free” foods are still recommended by well-intentioned medical doctors and dietitians, and the FDA has not announced any plans to revise their definition of “gluten-free.”

Now that you know the truth behind the “gluten-free” label, I encourage you to be your own solution by harnessing your power.

- If you’ve tried a traditional “gluten-free” diet and still have symptoms, check ingredient labels for gluten-containing compounds. It may be one of the triggers preventing you from achieving a full recovery. Keep in mind that gluten can be found in unexpected products, such as common table salt, which often contains a corn derivative used as an anticaking agent.

- Instead of trusting the “gluten-free” label, choose whole foods that are naturally gluten-free such as vegetables, fruits, meat from 100 percent grass-fed and grass-finished cows, pastured chickens and eggs, and wild-caught fish.

- If you want to avoid glutens, be cognizant not only of what you put in your mouth but also what you put on your body. Many personal care products, household cleaning products, and other items such as the glue on the back of stamps or envelopes can contain grain derivatives. Even toothpaste commonly contains at least one grain-derived ingredient.