Are We Heading for Another Great Crash (of 1929)?

CommentaryI have studied quite extensively the stock market crash of October 1929, and the Great Depression of the 1930s that followed, for a book I am writing on crisis forecasting. I recently noticed that the current economic and financial conditions have started to align with those that preceded the “Great Crash” in a rather worrisome way. The “Wall Street Crash” occurred after a lengthy economic boom period, dubbed the “Roaring ’20s,” which I briefly summarize as follows. After World War I had decimated Europe, the United States became a dominant global power. It quickly became the world’s leading exporter and the second as an importer. Between 1924 and 1931, the United States also was responsible for about 60 percent of global international lending, effectively making her the ‘world’s banker.’ The U.S. economy was booming. By the end of 1928, the U.S. economy had grown by close to 40 percent from the dismal year of 1921. The Federal Reserve index of industrial production had almost doubled (it did double when reaching its peak in June 1929). Wages hadn’t risen so much, but prices were stable. Business earnings rose rapidly. The newly formed central bank, the Federal Reserve, kept interest rates low throughout the 1920s, fueling the economic boom. As the world was on a gold standard, the economic boom drew a vast amount of gold reserves into the United States. However, the Fed let the share of gold reserves to notes (cash) in circulation rise, effectively ‘sterilizing’ all gold inflows from abroad. This was seen as the main contributor to keeping consumer price inflation at bay. While the money stock of the United States was kept at bay by letting the share of gold reserves to notes rise, this also meant that interest rates were kept relatively low. That led to heavy speculation in the asset and real estate markets. The credit boom intensified, peaking in 1925, and again in 1927. A noticeable industry of nonbank lenders developed during the 1920s, which fueled the boom in consumer durables, the commercial property market, the automobile industry, and in the stock market. A change in the mindset arrived in January 1928, when the Fed decided that the era of easy money (i.e., cheap credit) should end. It began to sell its government securities, consequently diminishing the supply of money, and it gradually raised the discount rate, which determines the interest rate that banks are charged on their loans from the Fed, to 5 percent from 3.5 percent. However, the policy had unintended consequences, as higher rates made more funds available to stock market speculation from nonbank sources. Because call rates for margin loans rose, it became profitable for banks to borrow cheaply from the Fed and lend the money to speculators with a very good margin. A window for great arbitrage trading opened to all banks, thereby feeding the stock market frenzy. The prices of stocks rose three-fold between 1927 and August of 1929. The first hints of a slowing economy came in July 1929, when the index of industrial production of the Fed dropped (there were, e.g., no quarterly earnings reports). From then on, several other indexes, including steel production and freight-car loads, started falling. The mix of bad news and rising interest foretold an upcoming recession, and the markets started to drift downward after hitting an all-time high on Sept. 3, 1929. On Oct. 24, the market opened in unspectacular fashion. Prices hovered for a while, but then started to fall rapidly, and the stock ticker, transmitting stock price information over telegraph lines across the United States, started to lag. The pace of sell orders grew at an increasing rate, and by 11 a.m., ferocious selling had gripped the market. A few selected quotations given by the ticker showed that the current values were far below the now seriously lagging tape. An overwhelming number of margin calls rolled in, and many investors were forced to liquidate their holdings. Increasing uncertainty made investors even more scared, and the selling turned into a full panic. The frenzy of selling could be heard outside the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where crowds started to gather. The police commissioner dispatched a special police detail to Wall Street to ensure peace. At 1:30 p.m., the vice president of the NYSE, Richard Whitney, appeared on the trading floor and started making large purchases of different stocks. This had a clear message: the bankers had stepped in. The effect was immediate: Fear vanished and prices boomed. On Oct. 25 and Oct. 26, prices held up during a heavy volume of trading, but on Monday, Oct. 28, the market opened to an uneasy tranquility, which was quickly broken. Selling started, accelerated, and by noon, the market was in the grip of a relentless selling panic. Bankers gathered, but the savior was never seen on the floor of the NYSE. On Oct. 29, selling orders flooded the NYSE at the open, and prices plunged, feeding the panic. Se

Commentary

I have studied quite extensively the stock market crash of October 1929, and the Great Depression of the 1930s that followed, for a book I am writing on crisis forecasting. I recently noticed that the current economic and financial conditions have started to align with those that preceded the “Great Crash” in a rather worrisome way.

The “Wall Street Crash” occurred after a lengthy economic boom period, dubbed the “Roaring ’20s,” which I briefly summarize as follows.

After World War I had decimated Europe, the United States became a dominant global power. It quickly became the world’s leading exporter and the second as an importer. Between 1924 and 1931, the United States also was responsible for about 60 percent of global international lending, effectively making her the ‘world’s banker.’ The U.S. economy was booming.

By the end of 1928, the U.S. economy had grown by close to 40 percent from the dismal year of 1921. The Federal Reserve index of industrial production had almost doubled (it did double when reaching its peak in June 1929). Wages hadn’t risen so much, but prices were stable. Business earnings rose rapidly.

The newly formed central bank, the Federal Reserve, kept interest rates low throughout the 1920s, fueling the economic boom. As the world was on a gold standard, the economic boom drew a vast amount of gold reserves into the United States. However, the Fed let the share of gold reserves to notes (cash) in circulation rise, effectively ‘sterilizing’ all gold inflows from abroad. This was seen as the main contributor to keeping consumer price inflation at bay.

While the money stock of the United States was kept at bay by letting the share of gold reserves to notes rise, this also meant that interest rates were kept relatively low. That led to heavy speculation in the asset and real estate markets. The credit boom intensified, peaking in 1925, and again in 1927. A noticeable industry of nonbank lenders developed during the 1920s, which fueled the boom in consumer durables, the commercial property market, the automobile industry, and in the stock market.

A change in the mindset arrived in January 1928, when the Fed decided that the era of easy money (i.e., cheap credit) should end. It began to sell its government securities, consequently diminishing the supply of money, and it gradually raised the discount rate, which determines the interest rate that banks are charged on their loans from the Fed, to 5 percent from 3.5 percent.

However, the policy had unintended consequences, as higher rates made more funds available to stock market speculation from nonbank sources. Because call rates for margin loans rose, it became profitable for banks to borrow cheaply from the Fed and lend the money to speculators with a very good margin. A window for great arbitrage trading opened to all banks, thereby feeding the stock market frenzy. The prices of stocks rose three-fold between 1927 and August of 1929.

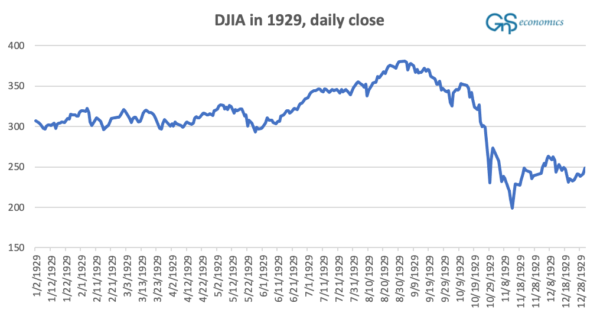

The first hints of a slowing economy came in July 1929, when the index of industrial production of the Fed dropped (there were, e.g., no quarterly earnings reports). From then on, several other indexes, including steel production and freight-car loads, started falling. The mix of bad news and rising interest foretold an upcoming recession, and the markets started to drift downward after hitting an all-time high on Sept. 3, 1929.

On Oct. 24, the market opened in unspectacular fashion. Prices hovered for a while, but then started to fall rapidly, and the stock ticker, transmitting stock price information over telegraph lines across the United States, started to lag. The pace of sell orders grew at an increasing rate, and by 11 a.m., ferocious selling had gripped the market. A few selected quotations given by the ticker showed that the current values were far below the now seriously lagging tape.

An overwhelming number of margin calls rolled in, and many investors were forced to liquidate their holdings. Increasing uncertainty made investors even more scared, and the selling turned into a full panic.

The frenzy of selling could be heard outside the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where crowds started to gather. The police commissioner dispatched a special police detail to Wall Street to ensure peace. At 1:30 p.m., the vice president of the NYSE, Richard Whitney, appeared on the trading floor and started making large purchases of different stocks. This had a clear message: the bankers had stepped in. The effect was immediate: Fear vanished and prices boomed.

On Oct. 25 and Oct. 26, prices held up during a heavy volume of trading, but on Monday, Oct. 28, the market opened to an uneasy tranquility, which was quickly broken. Selling started, accelerated, and by noon, the market was in the grip of a relentless selling panic. Bankers gathered, but the savior was never seen on the floor of the NYSE.

On Oct. 29, selling orders flooded the NYSE at the open, and prices plunged, feeding the panic. Sell orders from all over the country overwhelmed the ticker and sometimes also traders. At times, there were countless selling orders, but no buyers. This meant that during those times, the market was in complete free-fall. While there was a brief rally before the end of trading, “Black Tuesday” became one of the most brutal days in NYSE history, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) falling by 11 percent, on heavy volume.

So within a week, from Oct. 23 to Oct. 29, the DJIA lost 29 percent of its value; but the worst was still to come. From the peak on Sept. 3, 1929, through July 8, 1932, the DJIA fell more than 89 percent, fueled by the Great Depression.

What Are the Similarities?

Asset markets have rallied heavily, especially since 2020, and the value of the DJIA has risen approximately fivefold since hitting the cycle bottom on March 6, 2009. During the Roaring ’20s, the value of the DJIA nearly increased sixfold. Speculation in the financial markets has been rampant, which has been visible, for example, in the massive increase of margin debt and record-low yields of “junk bonds.”

Essentially, falling yields, due to the quantitative easing (QE) programs of the Federal Reserve, have pushed investors into riskier and riskier products and to use higher and higher leverage. Now, the first signs of a recession have emerged, and they are likely to continue to gather.

Thus, the situation in financial markets is actually even worse than it was in 1929. The Fed has been pushing vast amounts of “artificial liquidity” into the financial markets through the QE programs, but it’s now in the process of withdrawing that liquidity through quantitative tightening.

Now, asset markets are facing a triple-whammy: The economy is entering a recession, interest rates are rising, and market liquidity is being drained.

Is there any other way this can end other than in a crash? In my upcoming newsletter, I will present some guidance on how to prepare for the coming crisis.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.